17. The Shape of Water (2017)

Guillermo del Toro’s The Shape of Water, while set in 1962 Baltimore, still plays out as a romantic modern fairy tale (The Purple Rose of Cairo meets La Belle et la Bête meets The Creature from the Black Lagoon) that wisely knits the never-ceasing discrimination and disrespect minority groups face all across North America.

Buoyed with grace, and grievous heartbreak from the astounding Sally Hawkins, this movie will have you believe without batting a lash that a mute woman, Elisa Esposito (Hawkins) and a hard-boiled egg-devouring piscine amphibious humanoid (Doug Jones) from the uncharted depths of the Amazon can fall in love.

With a perfect woozy score from Alexandre Desplat, expert lensing from cinematographer Dan Laustsen, dazzling production design from Paul Austerberry, and sensational special makeup effects by Jeff Derushie (and others), this empathetic, awe-inspiring ode to Old Hollywood and the heartstrings is del Toro’s generous gift to us all.

16. Embrace of the Serpent (2015)

Man’s connection to nature, the tragic loss of a conquered people, and the mean mysticism that’s carried along with it are at the heart-stirring center of Ciro Guerra’s Heart of Darkness-like adventure odyssey, Embrace the Serpent. The winner of the Art Cinema Award in the Directors’ Fortnight section at the 2015 Cannes Film Festival, this Amazon-set saga of spirituality and enveloping atmosphere is an opulent black-and-white affair that is fittingly plush in 35mm.

This is one of those great and tragic epic jungle films, like Werner Herzog’s Aguirre, the Wrath of God (1972) or Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now (1979), and like those films it was also made under extremely difficult conditions made palpable by David Gallego’s immersive cinematography. The Colombian landscapes are as majestic as they are menacing, making the forests a crazy-quilt of textures and ancient radiance. This isn’t just cinema, it’s a feat of luminous and everlasting strength.

15. Silence (2016)

An upsetting and immersive viewing experience, Martin Scorsese’s 25-years-in-the-making “passion project” is a religious historical drama in the same vein as Carl Theodor Dreyer’s The Passion of Joan of Arc (1928), Robert Bresson’s Diary of a Country Priest (1951), and Pier Paolo Pasolini’s The Gospel According to St. Matthew (1964).

Set in 17th century Japan, this harrowing, shocking, and emotionally resonant look at spirituality, human nature, and faith is a tour de force of, amongst other striking techniques; bold cinematic portraiture, shining godlike POV vistas, subjective camera embellishments and several examples of Yasujiro Ozu’s signature “tatami shot” (wherein the camera is placed at a low height, at the eye level of a person kneeling in prayer).

For Scorsese’s brilliant editor Thelma Schoonmaker, this is some of her finest work, and Silence is a visceral experience of sensations, traumatism, and anguish that ranks amongst their finest and most disquieting works.

14. Horse Money (2015)

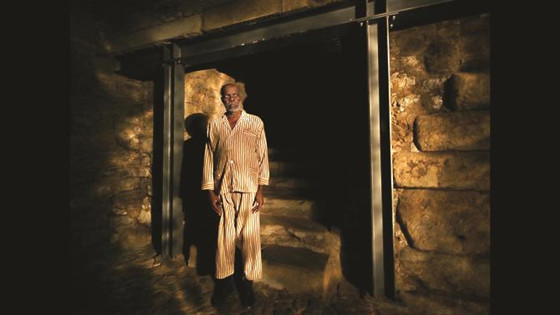

Pedro Costa’s nocturnal portrait of pain and piety blurs the line between documentary and fiction in the most fabulist of ways. Hazy, half-remembered hospitals and chiaroscuro apartment blocks beckon the viewer into modern day Lisbon and the life of a Cape Verdean survivor known only as Ventura (the actual nom de plume of Costa’s go-to leading man, in this, their sixth film together).

Costa and his genius cinematographer Leonardo Simões chronicle Ventura’s Joycean transmigration, a nighttime sojourn that doubles as an eloquent and memorable portraiture that’s as hypnotic as it is lamenting. It may not be feel good, but it feels mighty, and looks like a dark and unremitting dream.

13. Inside Llewyn Davis (2013)

The 2010s have seen brothers Joel and Ethan Coen continue to make some of the most exciting, innovative, and thrilling films of their careers, and this out-of-nowhere left turn into the New York folk scene of the early 1960s, and the listless eponymous folk singer, Llewyn Davis (Oscar Isaac) at its center may represent their finest cinematic outing to date.

Bolstered by French cinematographer Bruno Delbonnel (whose superb lensing history includes 2001’s Amélie, and 2009’s Across the Universe), Jess Gonchor’s faultless production design, and the Coen’s own impeccable editing prowess, Inside Llewyn Davis is all overcast skies, doleful folk, soured relationships, escaped cats, troubled troubadours, and all with no discernable direction home.

Astonishingly, the Coen’s have tapped into the deep well of clever and complex comedy à la Ernst Lubitsch, with compositions as eye-poppingly gorgeous as anything they’ve ever done. Don’t miss it.

12. The Master (2012)

Paul Thomas Anderson’s The Master presents a powerful and precise portrait of a troubled, violent, and often soused drifter named Freddie Quell (Joaquin Phoenix), suffering from shellshock after WWII he eventually, in 1950, runs into the charismatic cult leader Lancaster Dodd (Philip Seymour Hoffman). Mentoring Freddie, Dodd brings him into his religious movement, the Cause––a simulacrum for Scientology, and Dodd of L. Ron Hubbard.

A polarizing but prominent director, Anderson is, as Rolling Stone’s Peter Travers suggests, “…a rock star; the artist who knows no limits.” Travers goes on to say rather astutely that “ [The Master is] written, directed, acted, shot, edited and scored with a bracing vibrancy that restores your faith in film as an art form, The Master is nirvana for movie lovers. Anderson mixes sounds and images into a dark, dazzling music that is all his own.”

A compelling, challenging, frustrating and invigorating film, cinematographer Mihai Mălaimare Jr. (who deservedly won many awards for his fine work here), presents a fluid and unbroken chain of high contrasting imagery.

11. The Handmaiden (2016)

A distinct visual formalist, Park Chan-wook, the mad genius behind Old Boy (2003), and Lady Vengeance (2005), whose idiosyncratic yet technically complex style is assuredly at the fore of this ambitious and sweeping erotic thriller, based off of Sarah Waters 2002 historical crime novel, “Fingersmith.”

Set in 1930s Korea, with elaborate and impeccable period details, The Handmaiden follows Japanese heiress Lady Hideko (Kim Min-hee), who has been targeted by a slippery con man named Count Fujiwara (Ha Jung-woo) and a provocative pickpocket named Sook-hee (Kim Tae-ri).

The lush lensing of Chan-wook’s regular cinematographer Chung Chung-hoon provides painterly strokes to the artful yet explicit lesbian love scenes, providing lurid and memorable minutiae, and shocking set pieces, in what may just be Chan-wook’s most entertaining and saga-like work to date. A dark but delightful gem.

10. Moonlight (2016)

Writer-director Barry Jenkins, in adapting the marvellous Tarell Alvin McCraney play “In Moonlight Black Boys Look Blue” has fashioned a Florida-set coming-of-age odyssey that is both urgent and gravely moving. Simultaneously tender and tough, Moonlight brilliantly captures what it means to be a black man in contemporary America as Jenkins details the dysfunction and maturation of a young man named Chiron, a Miami resident amidst the crack contagion era.

Astonishingly brought to life by three different actors during different and defining stages in his life––Alex Hibbert as a child, Ashton Sanders as a teen, and Trevante Rhodes as a young man––rarely has an understanding of euphoria, longing, heartache, and grace been so triumphantly shared on screen.

You won’t find the expected stereotypes here, just sensual, expressive, and exhilarative expressions of humanity, black masculinity, and thrilling savoir-faire. Moonlight is pure, full-bloom, high-minded magic.

9. Cold War (2018)

Gracefully charting the delirious highs and heartbreaking lows of the excited love affair between a composer named Wiktor (Tomasz Kot) and a folk singer named Zula (Joanna Kulig) as they conform to the sour vagaries of life in post-war Poland under Communist rule, Pawel Pawlikowski’s Cold War is an achingly lovely achievement.

Like Ida (2013), Pawlikowski’s previous period drama, which also deserves a place on this list, Cold War shares a similar setting and luminous black and white view, but the two films are vastly different in their emotional approach and expression.

Kulig, as Zula, is absolutely electrifying. As she vibrantly descants Parisian torch songs that sets the enraptured mood of the film it’s easy to see why so many have suggested she may be the new Jeanne Moreau. With a sentimental sigh and a quick wiping away of tears, Cold War is a film of burning seduction and charming, cryptic truth.