5. Le Silence De Le Mer (Jean-Pierre Melville, 1949)

Jojo Rabbit recently told the story of people in World War 2, it threw away the ‘all Germans are evil Nazis’ trope and instead treated them like human beings. This is not a new concept though. No. Jeane-Pierre Melville did it, and he did it better.

Le Silence De Le Mer is the story of a French family, uncle and niece, Jean- Marie Robain and Nicole Stephane, as they reluctantly must house a German Lieutenant played by Howard Vernon. We expect a typical narrative of an abusive German throwing his weight around and dominating the household, but instead the story is a beautiful narrative about the similarities that exist no matter what walk of life you come from.

Every night the German Lieutenant stands in the living room of the man and niece trying to talk to them, he exposes his own feelings, trying to connect with them. The family stays silent, their own prejudice paints him as the face of the evil, but just like them, he is helpless. They are both just pawns. Both just humans. The film has been read to be a representation of Melville’s own struggles as part of the resistance during the war, a radical statement especially since the film was made so soon after the war. A very powerful piece of cinema.

4. Fruit of Paradise (Vera Chytilova, 1970)

Vera Chytilova is a true pioneer of the art-form. Her ground-breaking film Daisies would establish her as an avant-garde master, but it is her 1970 adaptation of the Adam and Eve story, Fruit of Paradise, that solidifies her legacy.

The film is a surrealist masterpiece that flows through the cinematic language without limitation. It is experimental and free from the constraints of narrative storytelling. While a narrative exists, it is not the driving point. The film instead creates a dreamscape to which the mythic bible story unfolds upon, but gone are the trappings of the classic story, instead the story is told from a female point of view. Chytilova questions everything about the origin story of ‘man’ and gives it a needed female voice. Satirical and political in all the right ways. A beautiful moment for feminist filmmaking.

3. Branded to Kill (Seijun Suzukui, 1967)

The Japanese new wave was a radical time for film. During the fallout of the war Japan found itself occupied by the allied forces and unable to have any true artistic output of their own. When the occupation ended Japan found itself scrambling to regain a sense of self identity and normality. The cinema became a haven for families and citizens trying to move on with life now that the past was behind them, but studios lacked the amount of material needed to meet the growing demands; hence, we find a moment in Japan’s history where left filmmakers were able to run wild: Japan’s new wave.

The studios would essentially green-light anything, and this is where we see some of Japan’s greatest filmic experiments, especially from director Seijun Suzuki, most notably known for Tokyo Drifter. Branded to Kill found Suzukui fired though, as the studio had lost hope in his ability to make films that ‘made sense’. He was the filmmaker that pushed them too far, but thankfully we still have the film that pushed them. Made on the fly, with almost no preparation, Branded to Kill is a stylish film about a hitman who is number two, but soon finds himself hunted by the ghostly number one. A true marvel of maverick filmmaking.

2. Sword of Doom (Kihachi Okamoto, 1966)

The Samurai film is to Japan what the Western is to America. When we think of the Samurai film we think of Kurosawa, a master of the form, but there were others, one of which was Okamoto, the director of Sword of Doom.

Sword of Doom is a meditation on the very narrative of the samurai. Here we are left questioning the realities of honour when it is so closely related to fighting and death. Here we examine the very probable realities of the psychological damage that would come from a life of violence. Here we examine the very role of a samurai and the films that depict them. It is best to know less about Sword of Doom, because we already have so many expectations of the genre that Sword of Doom works best when it can subvert them freely.

Sword of Doom stands neck and neck with the great samurai films of Japan and should not be allowed to fall into obscurity.

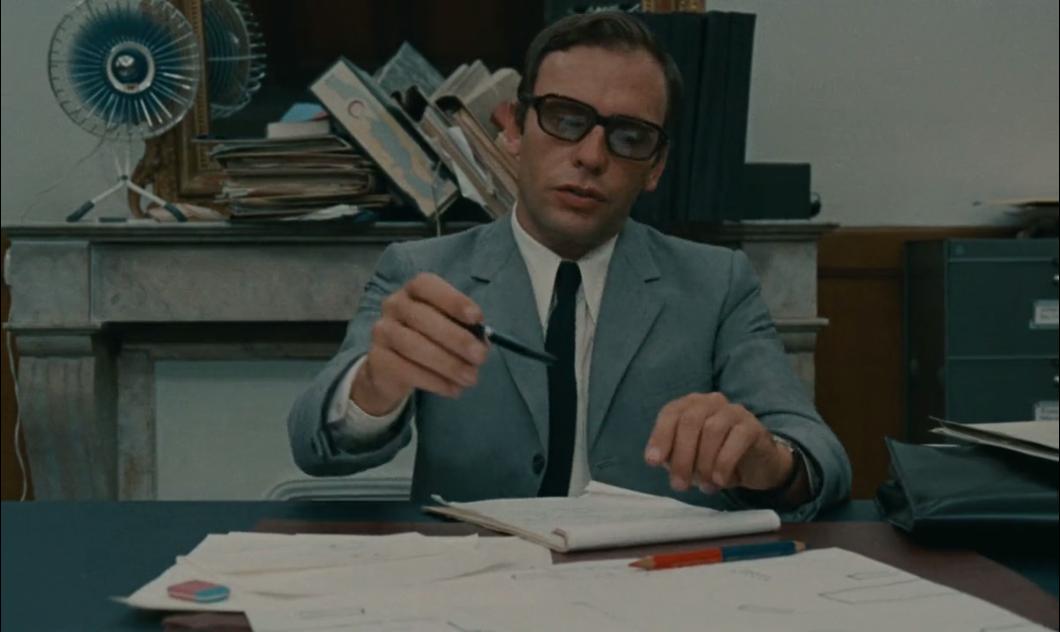

1. Z (Costa-Gavras, 1969)

Z is a film that leaves you drained in the best way. It is emotionally heavy but completely justified in its reasoning. The film is a fictionalised narrative influenced by the assassination of Grigoris Lambrakis. The film is satirical with a clear motive. It is a film that still today has so much to say and show.

Z interestingly was, like Parasite, nominated for best picture and best foreign language film at the academy awards, while it only won the latter, the fact that it was nominated in 1969 is a true testament to the magnitude of this film. While Z has somewhat fallen into history it is still a must watch film, and if that one-inch barrier is beginning to fall then what a place to start your journey into worldwide cinema with the film that almost achieved the same victory as Parasite over 50 years ago.