With Cyberpunk 2077 in development, the world seems to be once again enamoured with the virtual space of the Neo-Tokyo inspired worlds of cyberpunk. Films like, Blade Runner, Akira, Ghost in the Shell, and The Matrix seem once again in vogue, a testament to their timeless quality.

Cyberpunk goes far beyond the titular classics though; it was a sprawling genre that reflected an atmosphere unique to the ‘80s and ‘90s and offered countless texts to showcase it. After all, the world of the ‘80s was no longer obsessed with space, or distant worlds, instead storytellers wanted to explore cyberspace, virtual space, and the vast future that was promised by the new computer age.

The consumer technology of Japan was a domineering agent of socialisation, a catalyst for a new future, a future that was a cyber-influenced metropolis, a city built from the digital world, and it all seemed linked to the city of the rising sun, Tokyo. A glimmering example of what was next. films and literature often set the future in a pseudo-Asian world, a logical conclusion for the time, and a dazzling new landscape to explore, and rather importantly, a rather cheap vision to create.

Since it was easy to create the cyberpunk worlds of tomorrow, countless straight-to-video and independent features flooded the market, as they always do. films that were saturated with buzzwords like, hacking, virtual reality, data, cyberspace, and other computer inspired words ripe for a William Gibson novel. These films seemed to be everywhere as they no longer required sprawling sequences of space travel, instead all they needed was a neon glow, green tinted computer screens, and crazy body implants with a punk like spin to top it off.

It was the age of the hackers, the cyber-cowboys, the data-minors, but beyond the staple films, beyond the cash grabs, lies some forgotten films of the cyberpunk catalogue, a few hidden gems that are worth revisiting, films that still have things to say and show, and they are still a relevant example of what the genre has to offer.

10. Nemesis (Albert Pyun, 1992)

Albert Pyun is the king of the straight-to-video action film, he carved a career out of bad films that realistically hold no merit other than existing, that is true for all but one of his films, a film that is the culmination of everything ‘90s, that film is Nemesis.

Nemesis is not a good film, it mainly works as a cash grab rip-off, stealing from everything from Blade Runner to The Terminator, and yet, it somehow works. Nemesis has this style to it that exemplifies a ‘90s sense of ‘cool’ and ‘edginess’. The film feels like an advert for a Sega Genesis game, the kind of film that was made for a rental shop shelf, as its cover was enough to tell you it was going to be fun.

The story of Nemesis is rather poorly executed, it involves all the standard cyberpunk tropes, as Alex Raine (Olivier Gruner), traverses a future full of cyborgs, enhanced humans, and backstabbing governments. What Nemesis does do though is stand as an example of the trashy B-movies that flooded the market when cyberpunk was fashionable, and while it does fall into the bargain bucket of cheap genre videos, it’s the best of the bunch, a solid example of a cinema that has all but disappeared.

9. Split Second (Tony Maylam, 1992)

Split Second is often seen as a science fiction horror film, rightly so with its obvious Alien influence, but its cyberpunk markings are everywhere. The style of this film is cyberpunk through and through. The most interesting aspect of it though, the thing that sets it apart, is its setting, because unlike most cyberpunk films that operate in the seedy back streets of Neo-Tokyo, Split Second operates in the flooded back streets of England.

Split second focuses on cop Harley Stone, played by the legendary Rutger Hauer, as he slowly looses sanity over a string of killings that resemble the murder of his old partner. On a diet of coffee and chocolate, Stone slowly unravels the mystery of the killings. The result is a fascinating example of ‘90s science-fiction with a cyberpunk twist. It’s a mashup of genre traits wrapped in a dripping neon London. The aesthetic is a pure cyberpunk haven, yet the tone is a nightmarish noir, it feels like the birth child of Blade Runner, Ghost in the Shell, and Alien. A bizarre film that could only have existed in 1992.

8. Crazy Thunder Road (Sogo Ishii, 1980)

Director Sogo Ishii, now known as Gakuryu Ishii, is one of Japan’s most innovative filmmakers who pioneered a punk film ideology for Japan. His approach towards filmmaking and his ‘do-it-yourself’ attitude meant that he had two features under his belt before he even finished university, the latter of the two being Crazy Thunder Road.

Made to be his senior thesis for university, and then picked up by Toei studios, Crazy Thunder Road acts as a precursor to many of the staple attributes that would define the underground cyberpunk films of Japan.

The film is a neon chrome fever dream centred around the Maboroshi biker gang (very similar to the biker gang that would inhabit Akira two years later) and their internal conflicts, as leader Ken chooses a life of normality over the Mad Max-esque life of a gang leader.

The film feels like an extension of the Japanese new wave filmmakers with its playful demeanour and experimentation yet showcases a raw mentality that seems the logical artistic expression of the punk movement. While it may not be the most cyberpunk film on this list, it’s without a doubt a monumental precursor to the genre, and a technical marvel in terms of sheer filmmaking ability. A hyper kinetic film that is frantic and aggressive, all covered in a layer of leather, chrome, and neon. A film that puts the punk in cyberpunk.

7. Burst City (Sogo Ishii, 1982)

Two years later, after Ishii finally gets thrown out of university when it becomes clear that he is just prolonging his time there to have access to filming equipment, he directs Burst City, a tour-de-force of punk filmmaking.

Burst City doubles down on everything achieved in Crazy Thunder Road to the point of exhaustion, but not in a bad way, in a cathartic way. The film is a testament to everything Ishii presented during this period and is his final gift to the coming cyberpunk genre. It acts as a rule book for directing, as the camera is pushed to its limits, and the editing is strained to its breaking point.

This film holds no easy summary, Ishii wanted to represent what the essence of punk was, and with it he envisions a futuristic world inhabited by punks, biker gangs, yakuza, and anyone who got in the way. The result of the film is an almost endless conflict of ideology and philosophy, a formally free film, a film that seems more in tune with the rhythmic harshness of an overdriven guitar than any other piece of film. It is a visionary staple for the genre, and arguably the biggest catalyst for the cyberpunk films of Japan.

6. Adventures of Electric Rod Boy (Shinya Tsukamoto, 1987)

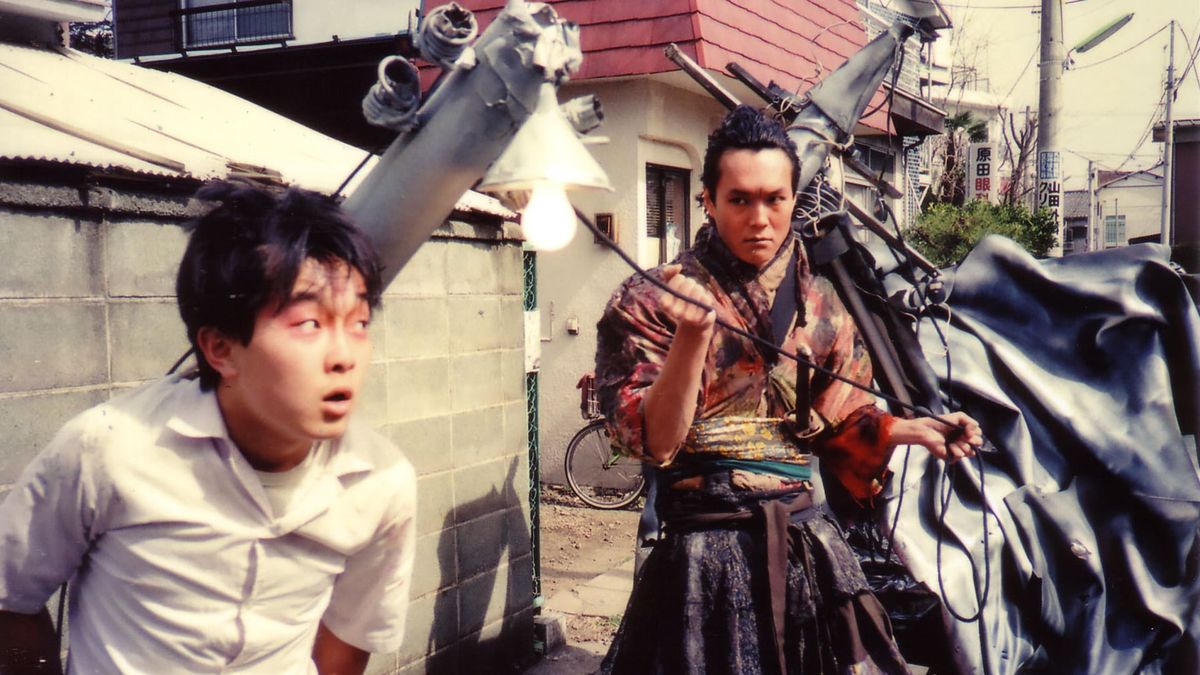

Shinya Tsukamoto directed one of the pinacol films of the genre, Tetsuo: The Iron Man, a visual masterpiece and defining film for the period. Before he created Tetsuo though, Tsukamoto was part of an experimental theatre group called Kaiju Theatre, a reference to his love of monster movies, and together the group created a stage play that would later become Electric Rod Boy. Since they had all the props, and Tsukamoto had a camera, it seemed logical to turn the performance into a film.

Adventures of Electric Rod Boy is born of the same ilk as many of Ishii’s films, after all, Tsukamoto attended the same school as Ishii and was rather jealous of his early success with film. It is to no surprise then that Electric Rod Boy shares the same frantic energy as Burst City and Crazy Thunder Road. The film feels young and formally free, and importantly it uses almost all the camera tricks that would soon be finessed in Tetsuo.

Electric Rod Boy is a manga influenced superhero origin story set to a cyberpunk formula. The stop-motion and kinetic camera begs you to think of Tetsuo, but the realisation that this is in fact the forerunner to the defining masterpiece makes it an essential piece of cinema history. Beyond its formal cinematic achievements, the film is a true inspiration for any independent filmmaker as it was made for nothing and even went on to win the grand prize at the PIA film festival, arguable the exposure that set Tsukamoto on his path to stardom.