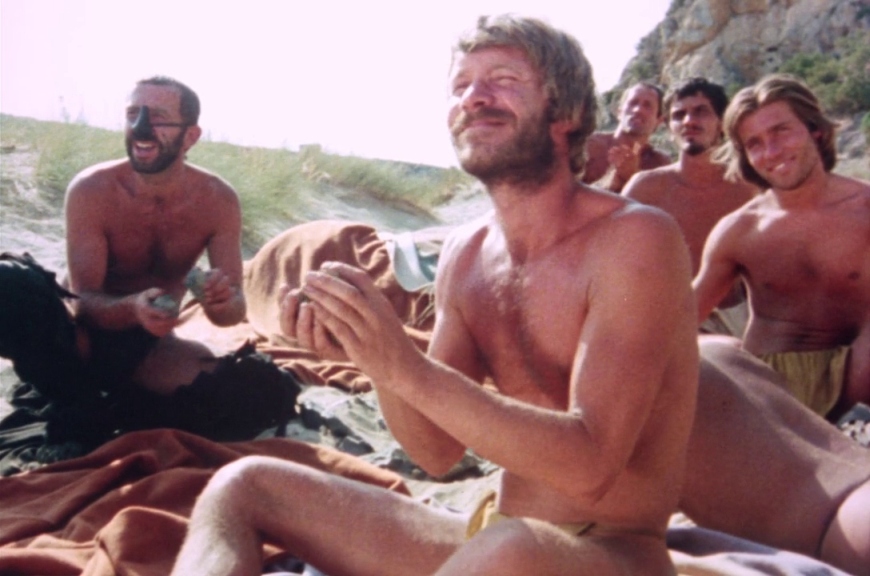

5. Sebastiane (Derek Jarman, 1976)

Derek Jarman – the writer, diarist, activist, gardener, and enfant terrible of British avant-garde filmmaking – began his filmmaking career set designing for films like The Devils (1971) for Ken Russell. His super 8mm experimental short films of around the same period were formally liberating and reflected the more liberal, open minded time. This was sustained in his debut feature film, Sebastiane, and reflected (possibly for the first time in film history) a positive and progressive representation of sexual liberation and homosexuality.

The film centres on the martyr, Saint Sebastian (Leonardo Treviglio), as he is exiled from his high military post to a remote coastal garrison where his rank is reduced to private. His pacifist views come to loggerhead with the garrison’s residing general (Barney James) who starts to abuse and assault Sebastian into taking up arms for the Roman Empire. This abuse turns into desire and the general’s sexual repression comes to the foreground as the soldiers around him intimately engage with one another, finding a solace in the boredom through passion and intimacy.

Sebastiane laid the foundations for Jarman’s radical and revolutionary work that was to follow and is a keystone in LGBTQ cinema. The entire film is in Latin too, of course.

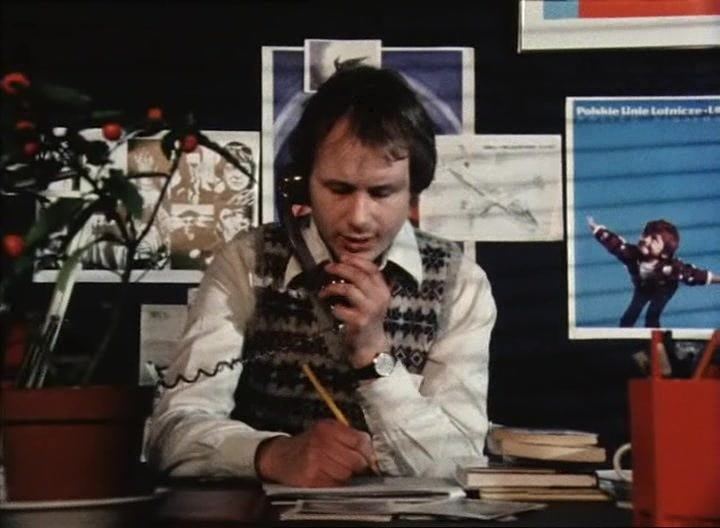

4. The Falls (Peter Greenaway, 1980)

In an alternate world struck by the VUE (“Violent Unknown Event”), this documentary recounts 92 entries into the directory of its survivors, their names all beginning with the letters FALL. The Falls is a bizarre retelling of the short stories of these survivors, told in documentary fashion where the deadpan narration contrasts the absurdity of the content – with brilliant and witty effect. Some survivors receive mysterious ailments, some are gifted with new languages, but it is Greenaway’s seamless blending of science fiction and the documentary that makes this bizarre story and audacious epic. It is stylistically delightful, funny, and intelligent.

Peter Greenaway would come to prominence making avant-garde narrative films like The Draughtsman’s Contract (1982), The Cook, the Thief, His Wife and Her Lover (1989), or Prospero’s Books (1991), but his first feature length film acts as the perfect bridge between his idiosyncratic short films and his fiction. Not for the faint hearted as it is 195 minutes long, but well worth the long haul.

3. Pressure (Horace Ové, 1976)

The same year as Jarman’s debut film also saw the first ever British feature film directed by a black man: Horace Ové’s Pressure. Ové was a Trinidad-born filmmaker, photographer, artist, and writer and would go onto become one of the most important and leading (if not the leading) figures in black British independent art and filmmaking.

Coming to prominence with his documentary Baldwin’s Nigger (1969), about James Baldwin and Dick Gregory’s London address on the black experience in America, Ové’s Pressure witnesses the development of the black power movement in London from the perspective of an England-born black adolescent caught between two cultures. Tony (Herbert Norville) is an educated lad trying to find accounting work to help supplement his family’s income but – much like his father 16 years previous – he is continually met with prejudice and abuse. This slow realisation of the bigotry of the white British community draws him closer to his activist older brother and makes him aware of his black consciousness.

A candid portrayal of social inequalities, generational division, and racial injustice, Ové debuted with a masterpiece and one that is as relevant now as it ever was.

2. The Seventh Continent (Michael Haneke, 1989)

Michael Haneke is a double Palm d’Or winning filmmaker with films The White Ribbon (2009) and Amour (2012). The same films were nominated for Academy Awards with the latter winning Best Foreign Language film. His other notable films include Funny Games (1997), The Piano Teacher (2001), and Caché (2005) that are all similar examinations of social issues and depict ordinary middle-class characters undergoing a psychological change due of their disillusionment to modern society.

But it is his debut feature, The Seventh Continent, that packs the real punch. A rhythmic exploration of modern life, we follow a bourgeois family over a three-year period as their mundane and uneventful existence starts to get the better of them and ultimately becomes their downfall. In true Haneke fashion, the ending is devastating and has a truly haunting impact – it is not for the faint hearted.

Here is another example of a film director kicking his career into gear with a true masterpiece and another film that laid the foundations for what was to come.

1. London (Patrick Keiller, 1994)

Artist filmmaker, Patrick Keiller, came to prominence making short documentary films that had a fictional edge. These films married handheld, architectural photography around London suburbs with a fictional voice-over that added the main narrative. His first short film, Stonebridge Park (1981), was inspired by a railway bridge in a London suburb and recounts the story of a petty criminal fleeing the murder of his old employer, ultimately instigating Keiller’s audio-visual style that would come to define his work.

This idiosyncratic film structure would come to a head in Keiller’s debut feature film, London (1994). An unseen, and unnamed, narrator (Paul Schofield) recounts his journey around London with his friend and lover, Robinson, an academic and researcher into the ‘problems’ surrounding London and city life. Set around the 1992 General Election, Robinson pines for the Romantic past as he and the narrator take excursions to the dwellings of various Romantic writers, witnessing urban decay, economic collapse, and other inequalities along the way. London would become the first of a trilogy of films by Keiller featuring the Robinson character with Robinson in Space (1997) and Robinson in Ruins (2010) – the latter being narrated by Vanessa Redgrave after Schofield’s death.

The essayist approach to filmmaking could be seen as influenced by the work of Chris Marker or the early films of Peter Greenaway, the poetic simplicity of the images akin to Humphrey Jennings or Alan Renais, but it is Keiller’s witty narration and seamless marriage of image and audio that stands him out from the crowd. London is neither fiction nor documentary but all the better for it. A psychogeographic masterclass.