There’s truth to the general belief that many debuts even from future famous and great directors lack polish compared to their more experienced, mature works. But it’s a more hidden truth that in many cases, a director’s earliest projects can have a certain youthful energy, refreshing brashness or undiluted simplicity of storytelling that can make it nearly or just as worthwhile (or in rare cases, even more so) than their later and better known work. These are especially fascinating cases where debut features feature themes that would become familiar in their directors’ oeuvre in ways that they’d never be seen again, or highlight themes and styles that they would later abandon.

10. Solo Con Tu Pareja (1991, Alfonso Cuarón)

A movie like this probably couldn’t still be made so easily or free of protest in today’s more politically correct times. Following commercial adman protagonist Tomás Tomás’ ongoing quest to bed as many women of as many types as possible before facing possible serious consequences, Sólo con Tu Pareja (“Only with Your Partner”) could’ve easily come off as just an asinine and monotonous — and to more sensitive audiences, repulsive — male sex fantasy movie. It’s a world where getting someone else’s bride in the woods right after their wedding, or getting a pretty nurse to follow up a routine blood check with special after-hours room checkups is all child’s play.

But Solo is too clever to be as limited as its main character’s mindset, and it embraces its absurdity (and sometimes even stupidity) amicably and wisely enough so as not to take itself even remotely seriously. The core and longest scene involves Tomas trying to entertain and “conquer” two women (one who’s his boss) in two different rooms of the same apartment complex at the same time without letting them know about each other through a combination of quick thinking (and lying), quick performing and risking his life by secretly switching rooms over and over via the balcony. Naked.

Director Alfonso Cuarón’s obsession with sex and the casual variety in particular followed from literally the very beginning of his career (at least in his Mexican films before mellowing out later); that is, from the first second of this movie’s opening shot with pretty much everything else in it to follow. Even the visual style reflects that, with a condom-filled mise-en-scene. There are also frequent sight and sound gags revolving around the act (women’s underwear floating down a building to the sound of a Mozart Serenade), pursuit/craving of it or fallout from it — the movie can’t even show a quick ariel view of random civilians from the top of a building without having them feeling on a statue’s breasts! For some it may be hard to believe this is how the Oscar-winning director of Roma started.

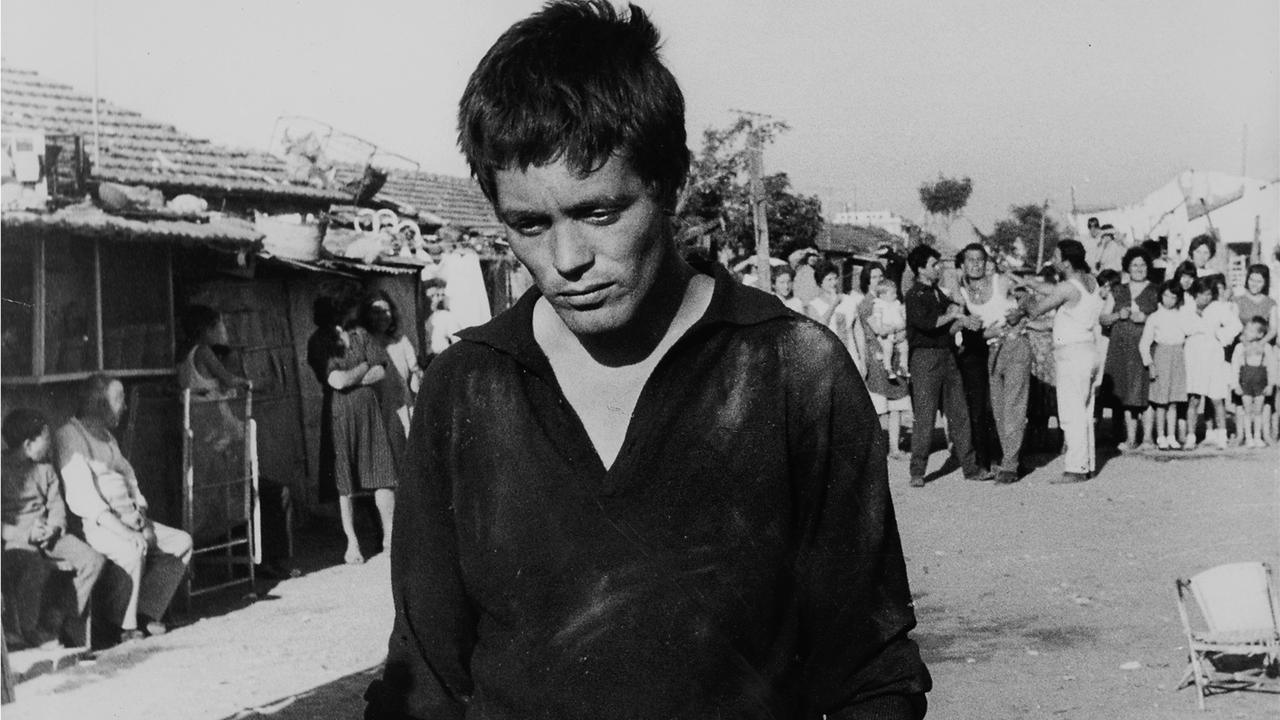

9. Accattone (1961, Pier Pablo Pasolini)

Ballila: “Relax! For thieves, there’s no being unemployed!”

Accattone: “You’re lucky to be so secure. Look at all the thieves who are rich.” [i.e. politicians.]

From his debut here Pier Pablo Pasolini already displayed his brazen boldness and irreverence in subject manner. Accattone (Vagabond/Derelict) explores a squalid side of Rome where the only thing more foul than the neighborhood is its inhabitants, including its titular loafer pimp. It wouldn’t be easy to find earlier films anywhere that had a pimp as protagonist and depicted him as thoroughly human (even if far from very sympathetic) on top of that, with a detailed life (having a wife and child and an extremely uneasy relationship with them).

Accattone is probably not well-suited for many modern audiences with its usually slow pace, poor picture quality and sometimes documentary-like format. But it remains remarkably original and bold, showing pimping isn’t necessarily always just about abusing or warning women about having their money on time (this one’s usually whining to them about that instead), as Accattone has an ambiguously communal relationship with his women and a dubious sense of pride in “taking care” of them.

Then there are the film’s frequent sarcastic asides, jokes and jabs at clergy, politicians and Italians’ ironic fixation on both no matter how steeped in vice society and popular culture actually was. That kind of artistic gall resulted in an angry fascist group attacking a theatre showing this film. Such extreme controversy, threats and violence would continue to follow Pasolini’s career, from having to fight a jail sentence for “offenses” against Christianity and Italy for 1963’s La Ricotta short, up to his vicious and still-as-yet-unsolved murder in 1975.

Truth be told, as the artist (as Pasolini was indeed more than a filmmaker, also being an actor, intellectual, poet, painter and political activist) was one of the most notoriously acquired tastes among those often thought to be great directors, for some this debut will actually be more palatable than most of his more “mature” works. Because while Accattone is by all means edgy and provocative for its time like most Pasolini films, it’s free of what many felt to be the indulgent excess permeating his later ones that would cap with Salo: 120 Days of Sodom.

8. La Commare Secca (1962, Bernardo Bertolucci)

For a director who’d garner a reputation for always wanting to make films on a grand scale or with grand pretensions — including his most famous The Last Emperor and Last Tango in Paris, and the 5 hour long 1900 — Bernardo Bertolucci’s debut can feel refreshing in its brevity and frankness. Basically a “socialist realist Rashomon”, it tells the story of the murder of a prostitute in bits and pieces through the separate flashback accounts of five different suspects under interrogation, representing something of a cross-section of lower-rung Italian male society. The folksy soundtrack and delicate cinematography (even when showing the female victim laying in a field at the beginning) contribute to the candid realism.

But while ambiguity and relativity was the very soul of Rashomon and its message, La Commare Secca like a true grim reaper (as the film’s epilogue and English title went) strips it of its soul and places the story in a new world and context to accommodate a movement (socialist realism) that seldom believed much in ambiguity.

This film doesn’t care about establishing a deep or difficult mystery or sense of relativism, and in fact much of the narrative isn’t even relevant to the main mystery. Instead, Secca uses the Rashomon format mainly for the purpose of showing various kinds of lives in everyman Rome, their dynamics and how they intersect. It does maintain Rashomon’s idea of how untruth is inseparable from human nature, but it’s presented in opposite fashion as the camera tells us exactly when and why everyone’s lying — and under deliberate rather than subconscious motivations.

From a story by Pasolini (the two would come up helping each other; Bertolucci was assistant director for Pasolini’s debut, then Pasolini would write Bertolucci’s), neither he nor Bertolucci acknowledged the Rashomon influence, and the latter outright denied it. But from the theme and style right down to the key use of heavy rain in the story, that comes off as rather incredulous.

It’s possible that Bertolucci and Pasolini simply wanted to minimize any risk of having to face the same legal consequences that Sergio Leone would two years later for his unauthorized retread of Yojimbo. Either way however, that makes Bertolucci yet another but a less known case of major directors whose debut or breakthrough films (thus also overall emergence of their careers) were indebted to Kurosawa but nevertheless developed into important distinct voices in cinema themselves alongside Leone, Lucas, Eastwood etc.

7. Three Outlaw Samurai (1964, Hideo Gosha)

From the very start of chanbara (swordplay) champion Hideo Gosha’s debut, he discards and uproots typical notions of heroism: a valiant-looking ronin (played by genre stalwart Tetsuro Tamba) rushes to a farmhouse to find a kimono-clad maiden tied up with a bunch of scruffy men around her — but a few minutes later he’s helping them, not her.

As it turns out that the group of peasants actually took the daughter of their feudal lord hostage in order to demand relief on the crippling taxes he put them under, the ronin comes to tepidly sympathize with them (partially for free lodging and to “enjoy the show”). Within that situation, two more fearsome samurai eventually get involved in the standoff: one who’s a prisoner, freed to back government forces aiming to negotiate or force the release of the hostage (and annihilate the peasants either way); and one (played by famous Japanese Shakespearen Mikijirō Hara) who doesn’t really seem to give a damn at all, calling pretty much everyone from every side “fools” through the events.

TOS reflects an outlook and themes that would continue throughout Gosha’s career, but perhaps more bluntly than ever here: heroes that aren’t really even heroes unless by chance or by whim, and that the samurai era was actually a cruel, brutal world where peasants and women in particular are susceptible to all kinds of exploitation.

There was also a contemporary tinge to Gosha’s cynicism, as his jidaigeki films had an open class consciousness about them that stressed and often centered around the privilege, trust and impunity the upper classes (for the setting of his films, the samurai) enjoyed. In that way, some of the most telling scenes come naturally and seem uneventful compared to all the violence — as when the haughty Lord’s daughter is brought to “understand why they kidnapped [her]” upon having to eat the peasants’ meager and revolting food. In short, Gosha went far beyond the call here for what was just expected to be an extension of a TV series.

6. Violent Cop (1989, Takeshi Kitano)

“Beat” Takeshi Kitano would establish himself as a master of unifying beauty and brutality, with moments of calm or lyrical serenity in amazingly fluid transition to extreme violence and darkness. The director (and star of all his yakuza films) would become especially refined with that duality in his two most famous films in the West, 1993’s Sonatine and 1998’s Hana-bi, then get into more viscerally violent films starting with 2000’s Brother.

But the most unhinged of them all (which is saying a lot for the director) was actually his debut where he plays the titular lawman out to bust a drug ring and save his sister from it by any means necessary. Violent Cop’s less disciplined, more upstart nature allows it to revel more in its extremes, with a protagonist and overall action that can go from endearingly and quaintly comical in some parts (the way he punishes a juvenile delinquent in his parents’ house) to shocking and outrageous to the point the crime fighter may well be more criminal than the criminals. Few films start off so breezily fun to gradually build to an end so grimly nihilistic.

Quite fittingly, Violent Cop was originally set to be directed by Kenji Fukasaku, the foremost yakuza film director of his period. So when Fukasaku couldn’t coordinate his schedule to work with the very busy star, Kitano decided to direct it himself. Thus it ended up serving as the perfect symbolic transition of one seminal yakuza filmmaker who had pretty much left the genre by then passing the torch to another, as Kitano would go on to make that much bigger of critical hits (Sonatine and Hana-bi) and commercial hits (the Outrage series) in it for the decades to come.