5. Exiled (2006)

A quasi-sequel to his 1999 classic “The Mission” (also highly recommended), Johnnie To’s “Exiled” finds the director at his most stylized and assured: if “A Hero Never Dies” was the start of the modern To, with his updated take on the conventions of heroic bloodshed, then this 2006 movie is the consolidation of his place in the history of the genre.

The movie begins with a showdown in typically tense and stylish To fashion: an ex-gangster is hiding out, having abandoned his old life and started a new one with a family, when two groups of hitmen show up: all of his former Triad brothers, one group tasked with eliminating him and another to protect him. Instead of killing each other, however, they all join forces and become targets for the boss who ordered the hit.

To is one of the most versatile and socially conscious directors in Hong Kong: whether he’s doing a political Triad thriller (the “Election” movies), a romantic comedy (“Don’t Go Breaking My Heart”), a musical (“Office”) or a straight drama (“Life Without Principle”), the director uses the conventions and trappings of the genre he’s working within to explore the power struggles provoked by modern capitalist logic and the effects it has on individuals. Therefore, his movies, no matter how seemingly pulpy, always have a dark, cynical underbelly running beneath the cool surface.

“Exiled,” in that context, is a surprising exception: despite the abundant violence, blood, and uber-suave look, it’s one of To’s most sentimental films. He portrays those men’s friendship as a real bond that redeems the cruel world in which they live in. In that way, it’s the most similar he’s ever gotten to John Woo, a director he’s frequently compared to, because he manages to find real pathos in the relationships between the shootouts.

And speaking of those, one can’t be effusive enough about the action in “Exiled”; if only more action directors had the same talent as To for blocking, editing, and camera movement, mainstream cinema would be heaven. Flying curtains have never looked better than in the many scenes in this movie where gangsters shoot at each other through them, particularly one moment in the back half of the film, an all-timer.

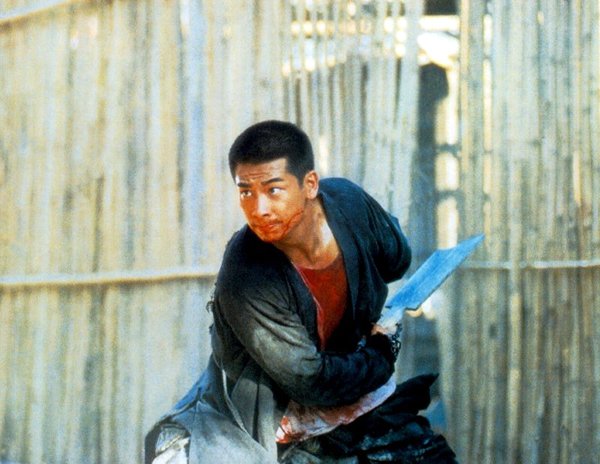

4. The Blade (1995)

Tsui Hark was one of the several New Wave directors who started in the late ‘70s with transgressive reimaginations of the classic themes and traditions of Hong Kong cinema, taking the aesthetic conventions of genre cinema and using them to convey nihilistic ideas about the moral underpinnings of those movies.

Eventually, Hark, like many of his contemporaries, was incorporated into the mainstream, but he never lost touch with his rebellious instincts. “The Blade” is the best junction of those sensibilities: a remake of Chang Che’s classic “One Armed Swordsman,” the film is very much the kung fu epic one had come to expect from Hark at that point of his career, but also a revisionist and quietly vicious take on wuxia that does away almost completely with Che’s vision of heroic men and replaces it with a cynical look at the codes that these characters live by.

It’s one of the meanest martial arts’ movies ever made; there’s very little attention paid to the usual themes of spirituality, honor, and brotherhood. Instead, Harks strips the genre to its basics, laying bare the violence at the core of every hero story.

However dour that description makes the movie seem, don’t worry – the action is still breathtaking, expertly choreographed and edited in Hark’s typically maniacal speed.

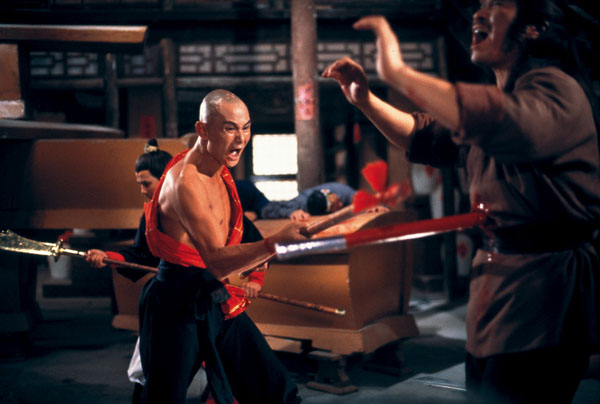

3. The Legend (1993)

From one of the darkest martial arts’ movies to one of the lightest: Corey Yuen’s “The Legend.” Yuen, of course, is a very familiar name to martial arts fans, being one of the most reliable supporting players in many kung fu classics from his fellow Peking Opera School students, like Sammo Hung. Long as his career as a performer is, however, it’s his work as a director that cemented his reputation as a legend of Hong Kong action.

The best movie he ever made is arguably 1993’s “The Legend of Fong Sai-yuk,” the purest distillation of his style that merges broad comedy with overwhelmingly complex fight choreography. In one of his best starring vehicles, Jet Li plays Chinese folk hero Fong Sai-yuk, who gets mixed up in a plot to overthrow the evil Manchurian emperor, all the while falling in love with the daughter of a rich merchant – an ally of the enemy.

“The Legend” is one of the rare examples, outside of the Jackie Chan movies, where the comedy and the kung fu work in unison rather than at odds. The exceptionally sophisticated timing of both the awe-inspiring stunt work and comedic gags is honestly comparable to Buster Keaton’s best hours – and the fact that such rich work is often ignored or ridiculed by Western audiences (even serious critics sometimes) only speaks to how action cinema (especially of Asian origin) is still underrated as a legitimately artistic endeavor.

2. Full Contact (1992)

The second Ringo Lam movie in the list, “Full Contact,” despite having a similar title, couldn’t possibly be any more different than “Full Alert”; if the later is a discrete and focused procedural, the former is a no-holds-barred action extravaganza, one that not only doesn’t make any excuses for its excesses, but actively delights in them. In fact, one could argue it’s a movie made of nothing but excesses and is all the better for it.

Starring the most iconic face of heroic bloodshed (and one of the greatest Chinese movie stars of all time) Chow Yun-fat, “Full Contact” begins as a heist thriller but quickly reveals itself to actually be a revenge story – not so much a subversion of expectation, just a natural progression of the narrative, one completely in keeping with Lam’s go-for-broke approach that mashes many disparate genre elements in a cohesive whole.

“Cool” is usually a terrible adjective to describe a movie – simply a lazy attempt to reduce the filmmaker’s stylistic choices to an easily understandable buzzword. That being said, I truly can’t think of a better term to define “Full Contact,” which features one of the coolest leading men ever to grace the screen in what might be his most badass role as the chain-smoking, vest-wearing, motorcycle-riding bouncer who gets double-crossed and comes back for retribution, in one glorious sequence after another. The movie is never just a cheap surface, however, since Lam infuses with enough underlying psychological darkness and downright nastiness that makes the tone more complex and difficult to pin down morally.

On top of everything else, “Full Contact” also features one of the best last lines of any action movie ever – you’ll know it once you hear it.

1. The 8 Diagram Pole Fighter (1983)

In a fair world, Lau Kar-Leung would be spoken of in the same breath as critically recognized masters of choreography like Bob Fosse, or storytellers focused on myth-like narratives such as Sergio Leone. In his best work, Leung was an almost unsurpassed genius at both and “The 8 Diagram Pole Fighter” finds him at his most mythic and with the most jaw-dropping, astounding can’t-believe-what-I’m-seeing choreography of his career.

With a darker, more serious tone than average Shaw Brothers fare, the movie begins with a tragic scene: the Yangs, a family of martial artists, is ambushed by a government official conspiring with the Mongols. Of seven brothers, only two survive: one who goes insane from shock and returns home; and the other, equally grief-stricken, who retires to a Buddhist temple in hopes of becoming a monk.

What follows is one of Lau’s most lyrical and sustained efforts of drama, as the characters genuinely (and surprisingly, for a kung fu flick) grapple with the emotional consequences of seeing your entire family killed in front of you. It is, naturally, hugely melodramatic in tone (it’s a Hong Kong movie, after all), something the director navigates confidently, with a visual style to match the larger-than-life nature of the story. The imagery is frequently primal and iconic, like the red-tinged opening fight (in the background, the costumes and, eventually, in the blood spilled).

And speaking of fights, it would be impossible to speak of “The 8 Diagram Pole Fighter” and not mention its action scenes, since the movie features some of the greatest fight sequences ever committed to celluloid, especially the duel between Gordon Liu and a monk and the insanely intense climax. If ever kung fu choreography was surpassed on film, it’s definitely in another one of Lau Kar-Leung’s masterpieces. When it comes to bodies in motion beating each other up on screen, the man was ever only in competition with himself.