When the word “franchise” comes to mind, many filmgoers only remember more big-budget, relatively recent Western ones like Star Wars, Fast & Furious and the superhero ones most recently dominating popular movie culture. But in the larger picture, a substantial amount of the biggest, longest-running and (by dedication of their followings rather than total numbers of viewers) most beloved film franchises are actually from before the 1970s, from Asia or developing countries, or in animation form.

So this list takes a look at some important franchises that slipped through the cracks of popular recognition or memory, yet did much to delight many fortunate enough to have been exposed to them and influence cinema both within their own countries and sometimes even Hollywood movies that lifted from them or built upon their foundations.

10. Tomie (1999-current)

This series based off of a manga from Junji Ito actually tended to be panned by the few mainstream critics who reviewed them. And indeed, “Tomie” (pronounced TOE-ME-EH) is one series that can widely vary in its quality level (and to a lesser extant in its degree of seriousness, level of horror or graphicness etc). But that’s natural and inevitable for a series that has completely different stories, actors, directors and staff on every installment.

The only thing technically the same are the Tomies, but even the Tomies are different Tomies: young girls linked only by their unexplained, probably supernatural attractiveness that makes men lose their minds and do unspeakable things over them, and the even scarier ability bordering on immortality to regenerate and duplicate every time one is killed (therefore, there’s technically a “real” Tomie all the others originated from).

That inconsistency has a big advantage as well: they allow much creative freedom and leeway for personalized interpretations of the character (defined most by the lead actress’ and director’s ideas about it). So in form it’s like an omnibus horror series like “The Twilight Zone” or “Tales From the Crypt” except that the “Tomie” episodes are all based around the same basic concept. In the West, Tomie is by far the lesser known of the “big three” movie/TV horror mega-franchises from Japan alongside “Ringu” and “Ju-on”, though in Japan it’s just as big.

The franchise has also served as an important springboard for several prominent Japanese actresses (including model/singer Miho Kanno who Ito chose to play the first Tomie on the first “Tomie”) and directors to make their names in the industry. It also helped established ones get helpful potboilers while still keeping their basic modes of expression. One standout case was Takashi Shimizu with 2001’s “Tomie: Re-birth” (starring Miki Sakai in one of the most amusing interpretations, giddily and playfully chiding characters for killing her before moving to kill them more permanently), who one year afterward would start his more internationally famous Japan-US “Ju-on”/“The Grudge” series.

Another is Shun Nakahara with personal favorite “Tomie: Forbidden Fruit” (2002), carrying over the light lesbian undertones of his sensitive 1990 signature work, “Sakura no Sono”, into dark overtones with a touchingly macabre father-daughter relationship and conflict as both fall in love with Tomie. Then there’s Noboru Iguchi — known for outlandish J-horror/exploitation films like “The Machine Girl” — naturally going over the top in his 2011 installment, the so-bad-it’s-good “Tomie: Unlimited”. Recently, the franchise is scheduled for its first Western adaptation as a Quibi streaming series.

9. Sartana (1968-1970)

After Sergio Leone’s “Dollars Trilogy” saw Clint Eastwood become an ironic American icon made in Italy, their spaghetti western genre would become an equally ironic national phenomenon in Italy that was primarily made for the American market. Soon the market had exponentially growing hordes of movies and actors imitating, adding their own spins to and/or blatantly ripping them off to varying degrees.

One of the more inspired but less known to follow that trajectory would be the 5-movie Sartana series (not even counting the many imitations of the original imitation to follow — another quirky spaghetti western trend). It’s true that this series is a tad trigger-happy and impatient even among westerns — hell, even among spaghetti westerns — as it can seldom even go five minutes without something or somebody getting shot, shot at or threatened to be shot (and is in fact more likely to have five people shot in one minute instead). But that energy precisely provided much of its appeal to its cult following.

Sartana’s ever-pale and ghastly countenance, plus his skill with knives in addition to guns and sometimes even cards help set the character apart, alongside even darker gallows humor than most other movies in a genre known for it. Yet perhaps the most eye-catching thing about the series lies within its very names: lurid titles you could only find in the wonderful world of Italian exploitation cinema like opening entry “If You Meet Sartana, Pray for Your Death”, and the 4th, “Have a Good Funeral My Friend… Sartana Will Pay!”

8. Young & Dangerous (1995-2013)

For the 1980s, 90s and 00s, Hong Kong cinema would have one triad (gangster) movie series that would largely define each of those decades: the 80s had the “A Better Tomorrow” trilogy and the 00s would have the “Infernal Affairs” trilogy. The one to define the 1990s would not get nearly as sizable of an international following as the other two, or as much influence in Hollywood (as “Tomorrow” would lead to Woo and a few other HK directors being recruited by Hollywood, and “Affairs” would lead to Martin Scorsese’s Oscar-winning remake “The Departed”). Understandably so, since “Young & Dangerous” is a lot more culturally and regionally esoteric and more rough around the edges, with indie-like production values for almost every installment.

But it was arguably the series that was needed the most, as it came during a particularly dark time in HK cinema when notable movies were few and far between. Unlike earlier popular action/emotional drama-oriented triad movies spearheaded by John Woo and Ringo Lam, “Y&D” would largely concentrate on the politics of the gang world, extensively showing them trying to make deals, create and settle conflicts, carve territories and decide who holds what position (with significant changes every time including new members, changes in hierarchy or character deaths).

But as formal as that sounds, the other half of the series was anything but, concentrating on the youthful and nonchalant nature of its lead Hung Hing Triad’s upstart members — meaning they’d as often just be screwing around (loitering, chasing girls, engaging in vulgar banter, clubbing, cruising etc.) as they’d be carrying out actual gang business. That youthful appeal ironically made the series very controversial at a time when it wasn’t easy to be controversial in HK’s anything-goes film industry at all; because many including government officials (perhaps reasonably) saw it as blatantly glamorizing gang life.

The series was so dominant during its peak time that it had almost as many spin-offs as it did main entries (including two of each released in 1996 alone), and additional movies unofficially connected but clearly inspired by and featuring some of the same staff/actors (like 1996’s all-female “Sexy & Dangerous” which happened to be Shu Qi’s non-erotic video screen debut). But a more serious female-oriented spinoff, 1998’s “Portland Street Blues” is actually one of the best with a story that takes itself more seriously.

Another fun entry of opposite nature is the Leslie Nelson-esque goofy 2010 self-parody “Once a Gangster…”. The series has bonus appeal for anyone with interest in Hong Kong for its heavy emphasis on the city’s real-life locations, geography, and challenges of trying to stand out as a big gangster in such a small, tight, densely populated city.

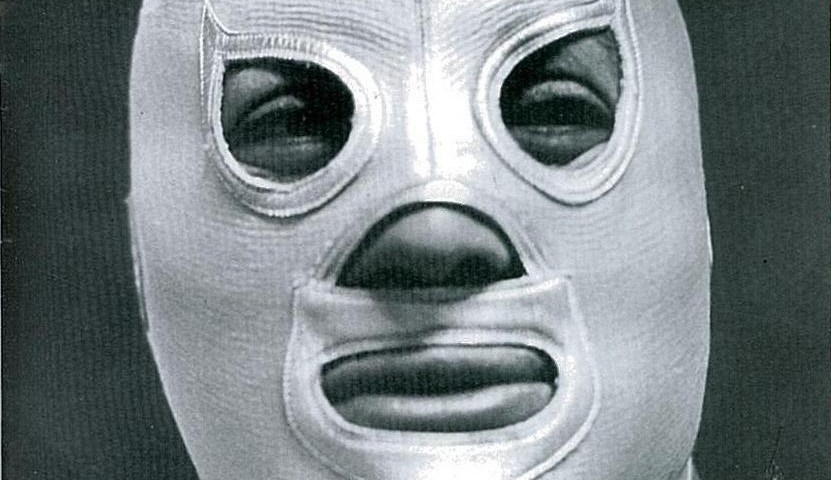

7. Santo (1961-1982)

In terms of how deeply they affected their countries’ national consciousness, Hulk Hogan and The Rock have nothing on Mexico’s El Santo (“The Saint”), as he became a cultural phenomenon on three different fronts: pro wrestling, comic books and movies. Santo became a hero for the downtrodden altogether to lengths unimaginable for a pro wrestler almost anywhere else. He also had tasks no other pro wrestler had to deal with, as not even The Undertaker ever had to face off against mafia, zombies, demons and enhanced human atoms.

The franchise is unabashedly camp (though unlike most Western camp like 1966’s “Batman” the actors take it all completely straight-faced and free of histrionics), yet unique for the fact it’s a pan-camp series covering most of that spectrum. Thus the kinds of movies the legendary luchador found himself in were often already indicated in the titles: “Santo vs Black Magic” is in horror movie territory, “Santo vs the Evil Brain” (not to be confused with another entry called “Santo vs the Diabolical Brain”, but that one too) is in science fiction territory, and “Santo vs the Strangler” has him in a mystery against a more realistic, giallo-like serial killer. But they all keep a kitschy air about their presentation and how freely they’re willing to mix up the superhero angle with the pro wrestling one, sometimes going as far as including entire 20-minute wrestling matches.

At times the plots even more bizarrely reach a crossroad where Santo the superhero still ends up having to fight the installment’s criminal/creature in the wrestling ring. Notice especially zany cases on 1962’s “Santo vs las Mujeres Vampiro” (the Vampire Women) where a “heel” wrestler turns into a werewolf at the end of the match, or “Santo vs la Invasion de los Marcianos” [the Martians] where the martian leader escapes Santo’s sleeper hold by (how else?) beaming up to his ship. More imaginative entries like that and “Santo Attacks the Witches” with its striking set design stood out among the whopping 50 movies the character was the protagonist of.

As if the originals weren’t already loco enough, Santo (or at least others donning his name & costume) also had a second “unofficial” career appearing in other countries’ B entertainment. The most notorious case was 1973’s bonkers Turkish superhero movie “3 Dev Adam” (3 Mighty Men) where he serves as Turkish Captain America’s sidekick against an evil, depraved Spider Man.

6. The Dead End Kids (1937-1939)

Generations before famous juvenile delinquent ruffian movies like “Kids” or “Slumdog Millionaire”, the Dead End Kids popularized and milked the concept. Unlike other franchises, they usually weren’t the stars per se but the focal points representing broken neighborhoods vulnerable to crime that Warner Bros then specialized in portraying.

They made their name (literally and figuratively) with a play called “Dead End” that was soon adapted into a 1937 movie directed by William Wyler. Rugged if somewhat compromised, that film helped solidify the rise of Humphrey Bogart in his role as a gangster who teaches the Kids to be better criminals in amusing fashion. Not minding being on the run as one of America’s most wanted, he’s still severely broken down by two women — his mother who disavows him and his lost love he has to bring himself to disavow upon finding out she’s become a prostitute with syphilis (in that quaintly subtle Code-era 1930s way).

1938 and 39 followups “Crime School” (also with Bogart) and “Hell’s Kitchen” seem dated in some ways, but are conceptually ahead of their time, featuring the impudent Kids trying to survive in highly abusive and corrupt reform schools. Ronald Reagan would also partially develop his career in “Hell’s Kitchen” (where he’s the only male character who’s relatively sane and free of gangster tendencies) and 1939’s “Angels Wash Their Faces”.

But standing head and shoulders above the rest is a masterpiece of the gangster genre, “Angels with Dirty Faces” (1938). There, “fighting Irish” delinquents James Cagney and Pat O’Brien do a robbery together as kids. The latter escapes to later become a priest, and the former gets caught and sentenced to reform school, coming out a seasoned gangster (who the Kids all follow and look up to much to the consternation of O’Brien) with Bogart as his slimy lawyer. The film is interesting and unexpected in how it portrays the priest and gangster relationship (as the two are still completely friendly and respecting towards each other even while warning each other not to get in their way/go too far respectively), and Father O’Brien’s one-second lapse back into sin when pushed to it in a bar is a classic moment in cinema.

While one could say they were a novelty act, the Kids were still quite an effective and influential one. But the end of their run — which fell just as suddenly and rapidly as it rose with six of their seven films in 1938 and 39 — was exacerbated by how they were as notoriously unruly and difficult to work with off the camera as their characters were on it. But they didn’t really reach a dead end from there, as they’d splinter into several loosely connected groups (like “East Side Kids”) for other studios to make an even more rapid assembly line of generally less memorable and successful movies. Nevertheless, their time in the sun in Hollywood was brief but glowing.