6. La Notte (1960, Michelangelo Antonioni)

A film about the emotions of emotionless characters, La Notte is the best representative of the chilling effect of a Michelangelo Antonioni film. It is this crisis the characters find themselves in that also makes the film difficult to enjoy. The cold deadpan style of the acting creates a distance between the two characters, but has an alienating effect on the audience as well.

Much like the solitary modern architecture of Milan where the story is set, there is an inescapable harshness to the civility of the character’s discontent. They refuse to explicate their suffering, making the film all the more sufferable to watch. At any time when the characters do express emotion, a barrier exists between either them or the action and the camera. The level of observation diligently remains a degree removed to contain any intimacy that finds its way into the frame. Those who make it to the film’s end are dealt a tragic coup de grace for their efforts.

7. The Color of Pomegranates (1969, Sergei Parajanov)

Sergei Parajanov’s biography of the life of the 18th century Armenian poet Sayat-Nova is unparalleled in its method. The film is commonly characterized as avant-garde and poetic, and for whatever those descriptions are worth, it is certainly that. More important is how it channels the unique capabilities of film to produce a work of art more comparable to religious paintings rather than other films.

Through materialism, process, dance, music, poetry, architecture, among other forms of ethnography, Parajanov renders an immersive experience into the history and culture that cultivated the life and mind of the great Armenian poet. There is a fixed frame approach to the cinematography. The camera is mostly static, as are often the actors who are positioned in poses, unless they are dancing, playing music, or performing some other movement in a carefully choreographed fashion.

Each object and action that occurs within the frame has a meaning that contributes to the telling of the story. The assembly of elements, such as a conch shell held to the breast in one hand and a peacock feather held in the other, follow an arbitrary dream logic, especially to someone who enters the movie cold. But the interaction of the symbolism gives the film its profundity. Scenes unfold like a series of iconographic paintings. Notice the heightened sound of monks slurping down pomegranate seeds or the splash of water during a foot bath. Few other films have a similar love for life that draws as much attention to that which life consists of.

Without any prior knowledge of Armenian culture or at least knowing who Sayat-Nova was, the content of the film is incomprehensible.

8. Stray Dogs (2013, Tsai Ming-liang)

An alcoholic father and his two children live on the torrentially soaked streets of Taipei. While the father works as a sign holder on a busy thoroughfare during the day, the children keep dry wandering supermarkets where they eat samples to stay fed. In public bathrooms and abandoned dilapidated buildings, the family performs their nightly routine of washing and preparing for bed. Emptiness is everywhere, in the lack of encounters and dialogue, the open spaces the characters traverse, and the vacant buildings they occupy.

With an eye for evocative yet oppressive imagery, Tsai Ming-liang’s Stray Dogs is nonetheless difficult to love. The use of excessively long takes and minimal dialogue require a degree of patience that some viewers will balk at. Tsai’s approach to time is comparable to the structuralist style cinema seen in the films of Chantal Akerman or Andy Warhol. For those willing to accept the slow pacing, there is a meditative quality to the film that gives the audience the opportunity to deeply experience the characters’ lives and the spaces they inhabit.

Many scenes are also static, without movement from the camera or the actors. When a cut finally comes, it doesn’t link together dramatic action as in most other films, but articulates the states of mind and emotional content of the characters. The order in which scenes are presented creates a relationship between them that is highly suggestive. Scenes are selective and minimal in content, stripped down to their most basic and raw elements. Tsai’s tactics may be pedantic to some, but they concentrate his subject matter to its most pure and poetic form.

9. Teorema (1968, Pier Paolo Pasolini)

Although the New Wave had lived and died by the time Teorema released, it has one of the best shot-on-location scenes of the 1960s, which is part of its fame among those who are yet to see it. The lives of a bourgeois Milanese family fracture into surreal dimensions after each of them have a sexual encounter with the same mysterious visitor. What writer/director Pier Paolo Pasolini is saying in this film is difficult to pin down, but easy to speculate because of the obtuse and ambivalent story.

A film that also revels in pessimism, its characters are as joyless as they are unsympathetic. Although the characters are intellectual and articulate, their intellect alerts them of their crisis, whether vocational, sexual, familial, spiritual, or otherwise, so they seldomly speak. This insistence on brooding can be infuriating to those wanting something more palpable and less abstract. The ending is also inconclusive. Yet the ambitions of the film go beyond the immediate problems of its characters. Its vision of a culture in crisis culminates in an unforgettable series of macabre and surreal scenes, staring into a void that most other films don’t dare glimpse at.

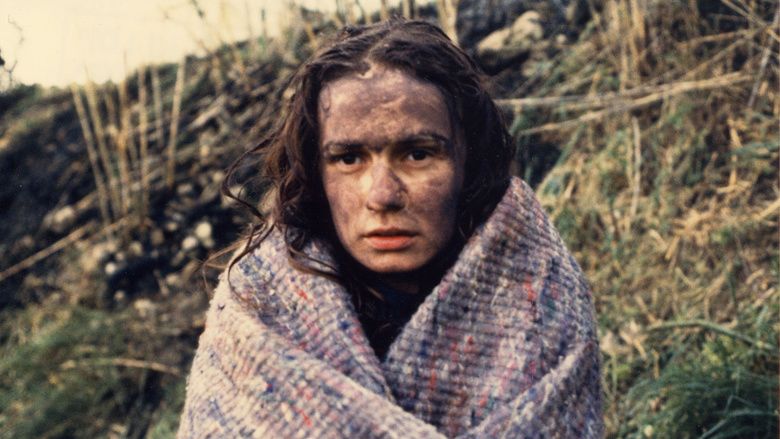

10. Vagabond (1985, Agnès Varda)

A young Agnès Varda said she had no interest in creating films that are pleasant to watch, but linger in the minds of viewers days and weeks after they have seen the film. Vagabond lives up to this ideal in its observational depiction of liberty and poverty. Rejecting the deadening expectations placed on a typical lower-middle-class woman, Mona embarks on a barbed homeless freedom wandering the countryside of France. The film’s French title, Without Roof nor Law (Sans Toit ni Loi) better communicates this idealism of the central character.

A testament to the film’s greatness is how Varda structures the narrative as an investigative documentary. The story reveals Mona’s doomed fate at the beginning to capture the audiences’ empathy, and to establish the mystery the film sets out to solve. Interviews of minor characters who encounter Mona punctuate each new chapter of her journey.

As the testimonials slowly reveal, Mona repetitively neglects the kindness of others to pursue a singular minded hedonism. Few personal details about her are learned. She avoids and deflects questions, insistent on maintaining her persona as a stranger. Those interviewed oscillate between respecting and condemning Mona, creating a moral question the viewer eventually has to answer for themselves. It’s this conflicted feeling for an unsympathetic character that makes the film hard to return to.