6. Harold and Maude (1971)

A fatalistic bourgeois teen with a penchant for the macabre has his faith in life restored when he meets and falls in love with an aging woman at a funeral. Confronting her mortality, the infectious joy Maude has for life teaches Harold to celebrate individualism and to live according to his own rules rather than the expectations of the high society he comes from. The unorthodox pairing form two symmetrical halves of the film’s rebel heart.

The story of the Byronic teen hero that meets the older woman who helps him navigate the stepping across into adulthood has a variety of earlier and later iterations, but Harold and Maude earn distinction for the peculiarity of its characters and the contributions of Cat Stevens to the soundtrack. Stevens’s If You Want to Sing Out, Sing Out defines the contagious spirit of the matriarchal heroine’s idealism. There are many admirable qualities about the film, but its soundtrack is among the very best of the genre.

7. Permanent Vacation (1980)

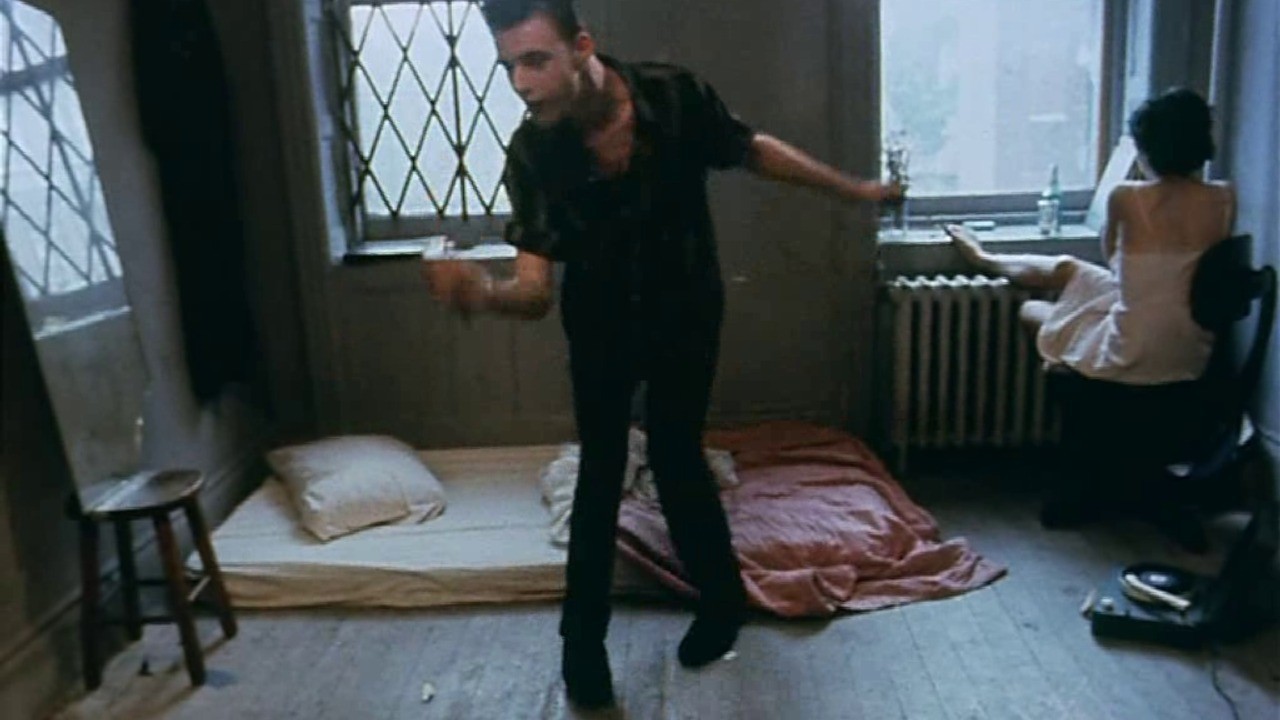

A more callous, impoverished interpretation of youthful independence that other directors would rather not admit, Jim Jarmusch’s debut feature Permanent Vacation crawls through the shuttered neighborhoods of Manhattan. Their bleak trash piles and emptiness are like urban graves that the curious yet self-absorbed protagonist Aloyisus wanders through. Defaced vagrants occupy the steps of eroding buildings. Graffiti stains the crumbling buildings that house the wretched Aloysius comes across in his aimless travels. In a film that centers on the luxury of living in the moment, Jarmusch perpetually brings urban decay into focus. The macabre mood that arises hints at the self-destructiveness of Aloysius’s free-spirited nature.

A camera aperture turned as far down as possible creates an atonal palette as dim as the Manhattan skies. The natural lighting also adds to the darkness of the film’s vision. A No Wave echo resounds in the harrowing chime of the film’s score. Glossy feel good perceptions of youth lose their fiction when confronted with this abrasive glimpse at one’s most narcissistic years.

While the film may have a crude presentation, for instance in its blown-out and crackling sound, there is a technical understanding of film’s unique powers as an art form from the opening frame. Take for example the initial establishing shot. On a busy street where the bourgeois and impoverished American dreamers brush shoulders, though usually barreling down the sidewalk with the velocity of a New York minute, are brought to an inert halt, whilst the sax of the busker shrunk in his corner plays at a normal pace. These peripheral and forgotten moments that capture the attention of those not yet integrated or avoiding the system are the ones Permanent Vacation likes to remind us of.

8. Slacker (1990)

Every other film of director Richard Linklater celebrates youth in one way or another, so let’s take the opportunity to honor his break-out feature since it lays the foundation from which his subsequent films spring from. Released independently, Slacker bums around the various circles of Austin can kickers, conspiracy theorists, street philosophers, creative idlers, and those who do not have any ambition to fit inside the pigeonholes parents, college, and society in general provide.

There are some noticeable rough edges to the film, such as the lack of professional actors, the occasional fumbling of lines, and the sound mixer dips the microphone into the frame during one scene. A colorful cast of characters and the method Linklater uses to thread them together makes these shortcomings forgivable. The camera movements track one group of characters, then similar to their short attention spans, focuses on someone else who incidentally enters the scenario, following their trail until it becomes bored with them and again finds a new personality to take an interest in.

Each scene shines a limelight on the principles, preoccupations, and obsessions of those normally kept out of focus. When practical middle age concerns close their talons around people’s necks, it bleeds dry the eccentrics of these unassimilated forward-thinking twenty-somethings. This is a film about those who are yet to give up on themselves for middle-class comforts.

9. Suburbia (1983)

Director Penelope Spheeris crafts a blend of reality and fiction in her debut dramatic release. Prepared to sleep in a ditch before enduring his mother go drunkenly berserk one more time, Evan abandons home seeking a riot of his own volition. The taste of cheap beer from last night’s punk show still on Evan’s lips, a benevolent punk rocker integrates him into the squat he has formed with other runaways and children of broken homes. While they find themselves embroiled in the consequences of typical teenage mischief, a pair of unemployed men focus their discontent on the misanthropic youth. A rivalry breaks out that exposes the gulf of the generational divide.

Ready to direct her fictional vision of the LA punk scene after the release of her documentary on the topic in The Decline of Western Civilization, Spheeris features local punk bands that give the film a degree of authenticity. Long sequences that use reverse angle shots between performances of local punk groups and the feral mosh pit below create an atmosphere of the type of rebellious freedom the characters are chasing. These sequences portray the barbed utopia of the punk rock sub-culture. Similar to its younger demographic, punk is also not invulnerable from the naive prejudices it has towards others, and Spheeris does not shy away from acknowledging that amid the chaotic fun of early independence and under-age drinking.

10. We Are The Best! (2013)

If there were one film you wish you could wrap your hands around and hug, it would be Lukas Moodysson’s We Are the Best! An aversion to gym class inspires three tween Swedish punk rockers to form a band, striking imprecise chords to the mantra “we hate sports”, then in the fashion of Swedish civility, hugging each other goodbye after practice. Rather than a shot/reverse shot that cuts one character off from the other to distinguish them, the camera opts for a pan between the characters that enfolds them like arms wrapped around one another. Each frame flutters with curiosity from the handheld cinematography, injecting each scene with intimacy. The slightly oversaturated complexion of the film adds to its warmth in the otherwise snow tumbling streets of Stockholm at Christmas.

Among the film’s thematic concerns, and this is common for the genre, is the feeling of being an outsider. The film examines this issue through a variety of topics, but most poignantly through the perception of beauty. Perspective shots that reflect the character’s image either through windows or mirrors bring attention to the discomfort of adolescent self-perception. Choosing protagonists who exhibit an androgynous punk rock aesthetic exacerbates this reality, and proves that among a band of outsiders, one can still feel alone.