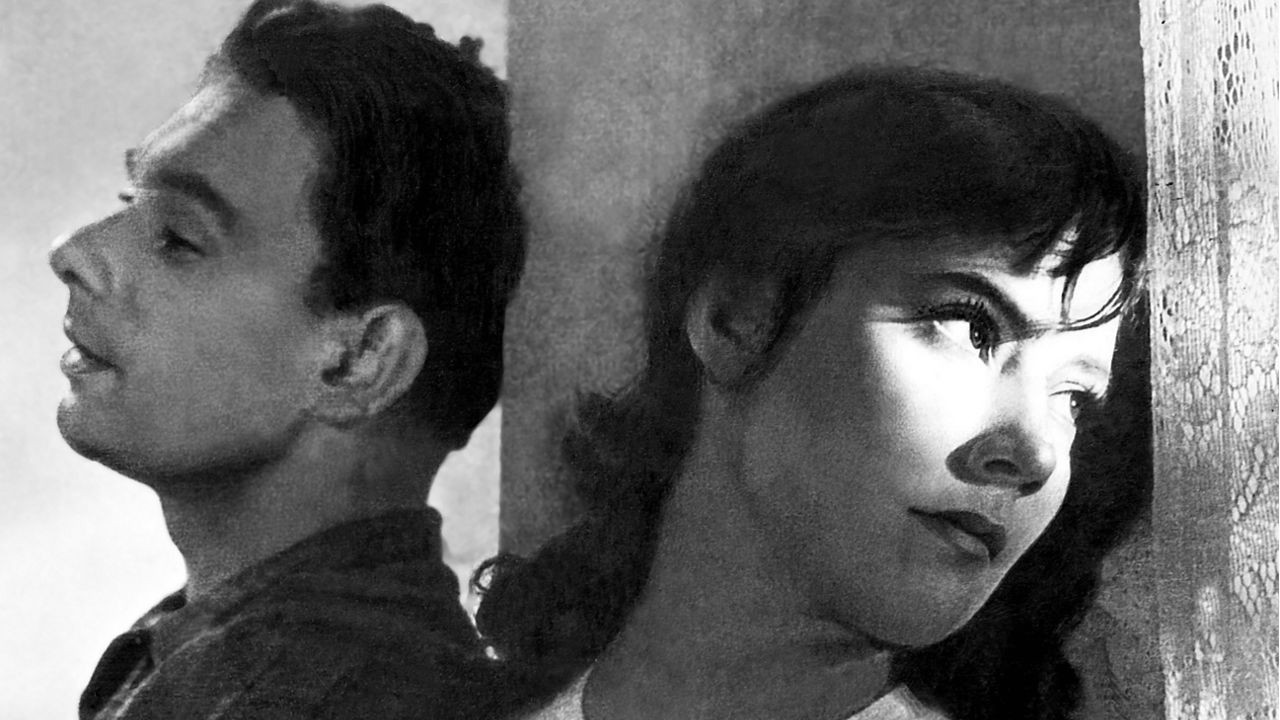

6. The Cranes Are Flying (1957)

A classic of Soviet-era film and one of the greatest war movies ever made, The Cranes Are Flying is the distinguished masterpiece of director Mikhail Kalatozov. The plot is a parallel narrative that traces the anguishes of war at home and on the front when the German invasion into the Soviet sphere rip lovers Veronika and Boris apart.

The filmmaking is overwhelmingly dense in its use of cinematographic, editing and narrative techniques, making it impossible to summarize but a wonder to watch. There is a generous use of Dutch angles, an oblique close up shot, that carries emotional impact but also skews the characters faces to suggest the uneasiness of their situation, context, and how off-center these circumstances place them. Comparable implications come from the haunting circular shots, sometimes sped up to a frenetic pace, of the towering trees and vaulting sky of the battlefield, having a dizzying and subliminal quality that forebodes of the imminence of death.

Feet are a reoccurring motif that draws similarities to the struggles of the characters despite experiencing two different faces of the war. A long tracking shot of Boris’ feet lunging through the mud juxtapose Veronika’s feet scurrying through the snowy streets of Moscow, linking their different hardships in the contrasting wartime theaters to visualize the intangible yet ubiquitous threat of danger, loss, and paranoia.

Whenever one mentions The Cranes Are Flying, in the next breath they mention lead actress Tatiana Samoilova. For her role as Veronika, she became the preeminent actress in the Soviet Union. Despite the craftsmanship of the film, it’s her performance that magnetizes audiences to the plot, personifying the confliction of a woman in love living in an ambivalent time.

7. The Elephant Man (1980)

For those familiar with the nightmarish surrealism of director David Lynch, his second debut feature may come as a surprise, not for its exceptional lucidity in the Lynch canon, but its compassion for the film’s titular protagonist. This is a biographical picture of John Merrick, nicknamed The Elephant Man, an Englishman born with a hideous physical deformity, unbearable for some to look at, casting him into the gutters of poverty where he works the underground circus as a human curiosity. Everyone views John as a monster, too concerned with the vanity of their disgust to bother asking John about his well-being, until a doctor known as Frederick Treves comes along and takes John off the streets and into his care. Treves learns that John is not the monster he appears to be, but a soft eloquent man that aspires to be of middle-class sophistication, his deformity being the only thing chaining him to the freaks and criminals he associates with for survival.

As John Hurt, who stars as Merrick, says, the basic premise of the film is that things aren’t always as they appear. The look of the film, shot in black and white, the masquerading macabre of the London poor all around, has the elements for a Victorian period horror film. Yet what the film becomes is a deconstruction of the horror movie villain, peeling back John’s boils and scales to reveal the intelligent and sensitive man clothed in monster skin. While this film may be somewhat of an outlier in the Lynch canon, one can still expect montage sequences of symbolic imagery and doomed billowing clouds in the night sky. These cerebral moments come as a reprieve from the emotionally tragic realism of Mr. Merrick’s story.

8. The Long Day Closes (1992)

A semi-autobiographical non-linear film from Liverpool native Terrence Davies, The Long Day Closes is a mosaic of dreams and memories that has a lucidity comparable predecessors couldn’t reach. Weaving in and out of the rainy alleys, solitary churches, and austere classrooms and townhouses of Liverpool, Davies reimagines his lonesome childhood in the character of Bud. Bullied and introverted, Bud quietly struggles to reconcile his religious upbringing with the realization of his homosexuality, finding a respite from his worries and the drab English background in the wonder of the cinema.

The tapestry Davies threads together follow an emotional logic that makes effective use of dissolves. Whether the narrative is moving forward or backward in time is never clear, but it is also irrelevant, since each sequence has a thematic link that the use of the dissolve clarifies. Davie’s affinity for the dissolve is in its power to dispense with the restraints of a linear narrative. Free from the shackles of traditional storytelling, Davies focuses his attention on the burgeoning moments that form Bud’s emotional content. This poetic form of cinema has the power to leave one in a rapt reflection of the imaginary nature of memory, and how they are more essential to who one is than the lived experience they recall.

9. Sansho the Bailiff (1954)

Of the many tragedies that make up the bulk of the filmography of Kenji Mizoguchi, Sansho the Bailiff ranks as the most shattering. Based on an ancient Japanese oral tale of the same name, Mizoguchi’s Shansho shines a dark light on the liberation of women.

In the chaos of the slavery system of Heian period Japan, a mother and her daughter and son travel the tumultuous path to the location of their father’s exile, but are abducted by slave traders. The children grow up in the slave encampment of a samurai, dreaming of the day of their escape when they can return to their parents. During their enslavement, the son starts to accept his status as a slave while the sister holds onto the convictions their father gave the pair as children. This distortion of strength between brother and sister, man and woman, specifically the power to endure, is the phenomenon that forms the basis of the film’s tragedy.

There are many notable elements of a Mizoguchi film, but few others can compare to the beauty of his framing. Unlike many comparable films, Mizoguchi doesn’t rely so much on the close-up, but instead on repositioning the camera in accordance with his actors’ movements. This constant framing and reframing extend the unfolding drama, favoring long takes, introducing and allowing characters to exit a sequence, and emphasizes the body language of actors to communicate the state of mind of their characters.

Earlier films of Mizoguchi focus on the Japanese theater, and the actor who plays the character of Zushiô, the son, is originally a stage actor, so naturally practices of the revered Japanese theater also characterize Mizoguchi’s style. The stage requires an enormity of movement from its actors to make the action dramatic, which is a feature Mizoguchi incorporates in Shansho. At the moments when the family splinter and then again when they eventually reunite, their spirits broken from the merciless tragedy committed against them, the pathos of the performances plunge to the brink of the human capacity for suffering.

10. Weekend (2011)

The premise of Andrew Haigh’s Weekend is as simple as it is universal. Two strangers, college students Russell and Glen, have a one night stand that echoes with the initial murmurings of falling in love. Glen reveals the next morning that he is departing overseas to attend art school, snuffing out the flame between them before it can emerge into the white blaze of passion it otherwise promises to be. The film is a melancholic examination of the fleeting nature of love that one experiences in their twenties, when it suddenly and unexpectedly arises, and one is as unprepared as the other for the commitment necessary to maintain the connection they yearn for.

One of the elements that universalize Weekend is the apocalyptic emptiness of the town where the romance occurs. The sleepy college town is indefinite, suggesting that the hope and loss the characters quickly experience could happen anywhere. Russell’s apartment building is one of the film’s favorite images to meditate. Every window in the sky-rise has the drapes closed shut or lights turned off, except for his, creating a sense of loneliness and alienation despite being among many people. When he gazes out at Glen exiting the building and walking through the courtyard, no other pedestrians wander by, as if Glen is the only other person in Russell’s shuttered world. This desolate cityscape channels how Russell views his homosexuality as an abyss, which no one other than Glen can guide him through.