The impact of Sergio Leone’s filmography is colossal. Many of Leone’s signature touches from his classic Man with No Name trilogy become norms in the Western genre. Ultimately, his tragically short filmography leaves one wanting more. Fortunately, a quick Google search of popular spaghetti westerns can offer a long list of films that very closely resemble Leone’s iconic output. Therefore, the purpose of this list is to uncover — for the most part — movies that unexpectedly reveal similarities to Leone’s signature style or sensibilities that most Google searches won’t offer.

1. Track of the Cat (1954)

William A. Wellman’s Track of the Cat is a bold American western, fusing elements of arthouse and melodrama. The movie follows a Califronian family isolated in a ranch. Gradually, they become overcome by domestic tensions, hostile weather, and fear of a panther supposedly prowling in the mountains. Wellmam, the director of Wings and The Ox-Bow Incident, conceived of the movie through its relationship to colour. The film relies predominantly on the high contrast between the overwhelming shades of white and black. With some vibrant exceptions, most other colours are muted. Indeed, it’s a heavily symbolic film and a definitive outlier in the landscape of 1950s westerns.

Far more subdued and foreboding than anything Leone ever touched, Track of the Cat nonetheless shares a similar taste for genre subversion. At a time when the western genre was dominated by John Wayne/John Ford or James Stewart/Anthony Mann collaborations, Wellman aspired to take the genre in a different direction. In Track of the Cat, everything is a metaphor and there’s no hint of glory in the Wild West. Other westerns of the era would still sometimes critique the idealized underpinnings of masculinity and racist American valor embedded in the genre. Yet Wellman’s film takes a more radical stance, revealing these qualities as myth from the very beginning.

2. Yojimbo (1961)

Cinema of the West owes a lot to Akira Kurosawa. Star Wars is, of course, The Hidden Fortress reimagined as a space opera. Even countless classics from the western genre are remakes or riffs on some of Kurosawa’s most iconic samurai films. John Sturges’ The Magnificent Seven is Seven Samurai with cowboys. Even Leone’s own A Fistful of Dollars is an unofficial remake of Yojimbo.The premise is the same: a lone figure finds himself in the midst of a conflict between two rival gangs and begins playing them against each other. However, Leone’s own creative impulses result in a very different movie.

Perhaps most notably, Toshiro Mifune’s performance is in stark opposition to Clint Eastwood’s. Mifune is wild, energetic and bubbling with violent glee. Eastwood is famously stoic, watching situations unfold without seeming particularly engaged. Yojimbo is, as a whole, some of Kurosawa’s most unrestrained action cinema. Mifune’s hacks his way through assailants, splattering blood and scattering limbs. Kurosawa collaborates with legendary cinematographer Kazuo Miyagawa, filming in stark, gorgeous black and white. The film’s aesthetics and temperament are vastly different from Leone’s rendition in A Fistful of Dollars. Yet the two distinct films are united by a gleeful predilection for suspense and deception.

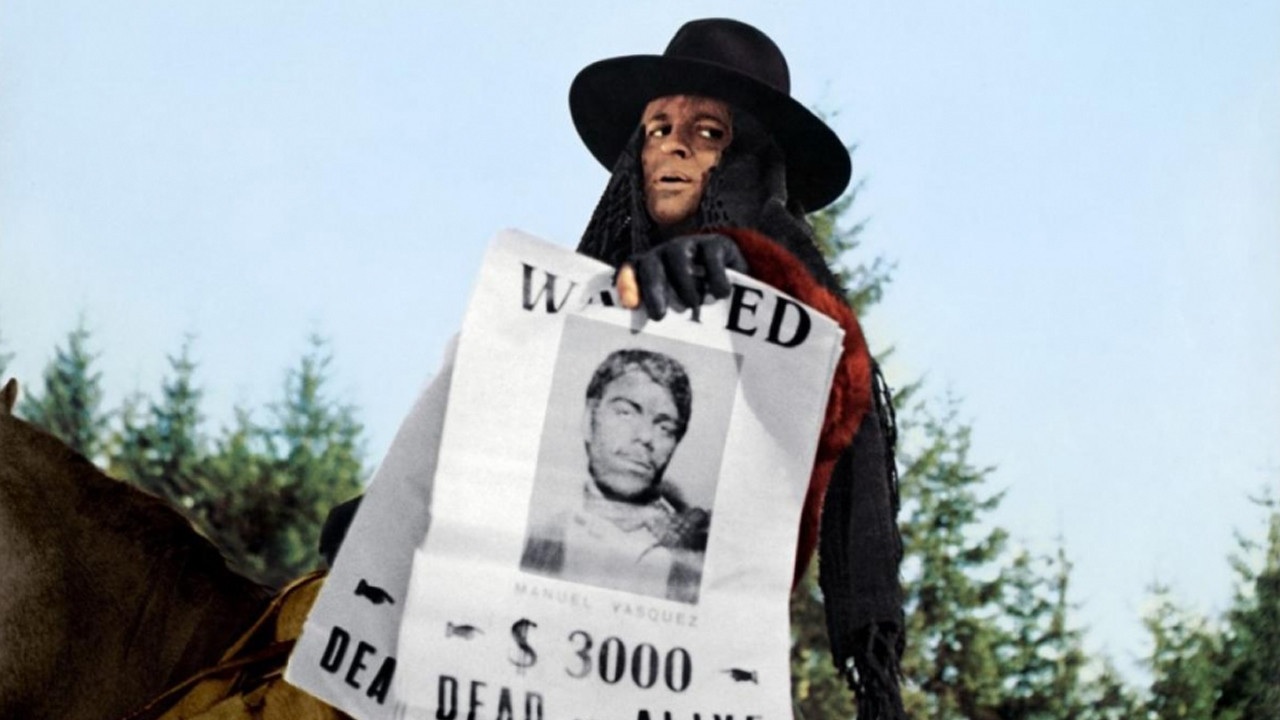

3. The Great Silence (1968)

Sergio Corbucci, a contemporary of Leone, delivered his magnum opus with The Great Silence. Jean-Louis Trintignant plays a mute gunslinger named Silence who’s hunted by a collective of bounty hunters led by a sadistic Klaus Kinski. While the movie leans into similar iconography and stylings as Leone, it’s ultimately far more mournful and elegiac. Even Ennio Morricone’s score avoids the grandiose dramatics he brings to Leone’s works, instead focusing on the sadness of the western. The film is among the western’s bleakest works, trampling over any sense of hope. Corbucci was influenced by the recent, tragic murders of Che Guevara and Malcolm X, and wanted to craft a condemnation of America’s eternal tendencies towards hatred and violence.

The Great Silence is packed with unforgettable imagery. Corbucci avoids the classic western landscapes of wide deserts and sun-glowing skies. His film is cold. Landscapes drown in thick snow, and a wild wind howls across the soundtrack. The warmth and radiance of the old John Wayne western is dead. The Great Silence is about a transition into a period without hope. In Corbucci’s western, there’s no room for heroes. His take on the spaghetti western is far more nihilistic than Leone’s. In The Great Silence, America is irredeemably broken.

4. The Wild Bunch (1969)

After the success of Italy’s spaghetti westerns, American westerns changed. It happened pretty abruptly with Sam Peckinpah’s The Wild Bunch, a film whose slow-motion, blood-splattering shootouts feel revolutionary to this day. The movie is far more chaotic than anything Leone ever released. With its signature quick cuts rapidly teleporting the camera across a battleground, it can be hard to follow the fight. That’s, however, what makes The Wild Bunch so mesmerizing. Peckinpah and his editor Lou Lombardo make visceral action scenes, prioritizing chaos over coherence. The film’s hectic cuts toss the audience headfirst into violent shootouts.

Peckinpah is a tremendous filmmaker, maligned in his own time and still underrated today. His films, bloodsoaked and gritty, introduced a newfound depravity to mainstream American cinema. However, his reputation as merely a sadistic artist feels reductive. Peckinpah was also an incredibly sincere filmmaker, deeply concerned both with how his characters repress their emotions and also the life-shattering consequences of violence. He wasn’t merely a trigger-happy lunatic.

There’s no better evidence than Pat Garrett & Billy the Kid, a film where countless acts of violence have severe and devastating emotional repercussions. This degree of sincerity is absent from much of Leone’s early work, but it begins to trickle in. By the end of his career, with Once Upon a Time in America, Leone’s relationship to violence had changed. America, like best Peckinpah’s work, is a film deeply concerned with the results of violence, both on its victims and its perpetrators.

5. 1900 (1976)

Bernardo Bertolucci’s 1900 is the director’s finest work. It’s a five-hour epic, tracking the history of Italy’s political landscape in the first half of the 20th Century. The movie follows two childhood friends (Robert de Niro and Gérard Depardieu) into adulthood. The men are opposites, raised from contrasting socioeconomic backgrounds and maturing into polarized ideologies. Bertolucci uses these characters to explore the clash between Italian socialism and fascism.

Leone’s films were never overtly concerned with political systems or ideology. However, 1900 bears the markings of a clear predecessor to Once Upon a Time in America. Some of the key players are present; De Niro and Ennio Morricone are some of both movies’ greatest assets. 1900, much like America, is concerned with tracing the evolution of a country through specific relationships. At the core of both movies is a tragic friendship. Bertolucci and Leone both shared a knack for capturing something grand and epic through moments of intimacy.

Unfortunately, 1900 was a commercial failure at the time of its release. Its catastrophic box office revenues drove producers away from the risk of distributing incredibly long films in wide release. As a result, Once Upon a Time in America was cut into an increasingly short film, until it was released domestically at almost half its full length.