6. Crime Wave (1985)

John Paizs probably isn’t a name you’re familiar with unless you’re a particularly keen enthusiast of Canadian cinema in the late 20th century; but if Crime Wave, his feature-length debut, is anything to go by, he deserves far more recognition than he’s ever received.

We follow Kim, a young girl living in a quiet Canadian suburb, and her fascination with Steven Penny, a young man renting the room above her parents’ garage. Steven is an aspiring screenwriter looking to create the next great “colour crime movie”; but though he’s written countless beginnings and endings for his new script, he can never seem to think up a middle part to connect them.

It’s hard to get into just what makes this film so weird without wandering into spoiler territory. Suffice it to say that this seemingly simplistic setup, which feels like it could be the foundation for a pretty muted comedy-drama, gradually takes on some very Lynchian qualities as the lines between reality and Steven’s scripts begins to blur, and various elements of magical realism begin to seep into this seemingly mundane setting. This, combined with the film’s quietly anarchic style (it merrily flips between being reminiscent of a classic noir and a corny mid-20th-century educational film with little transition), makes for anything but what you’d expect from the first impressions the film offers.

7. We Are the Strange (2007)

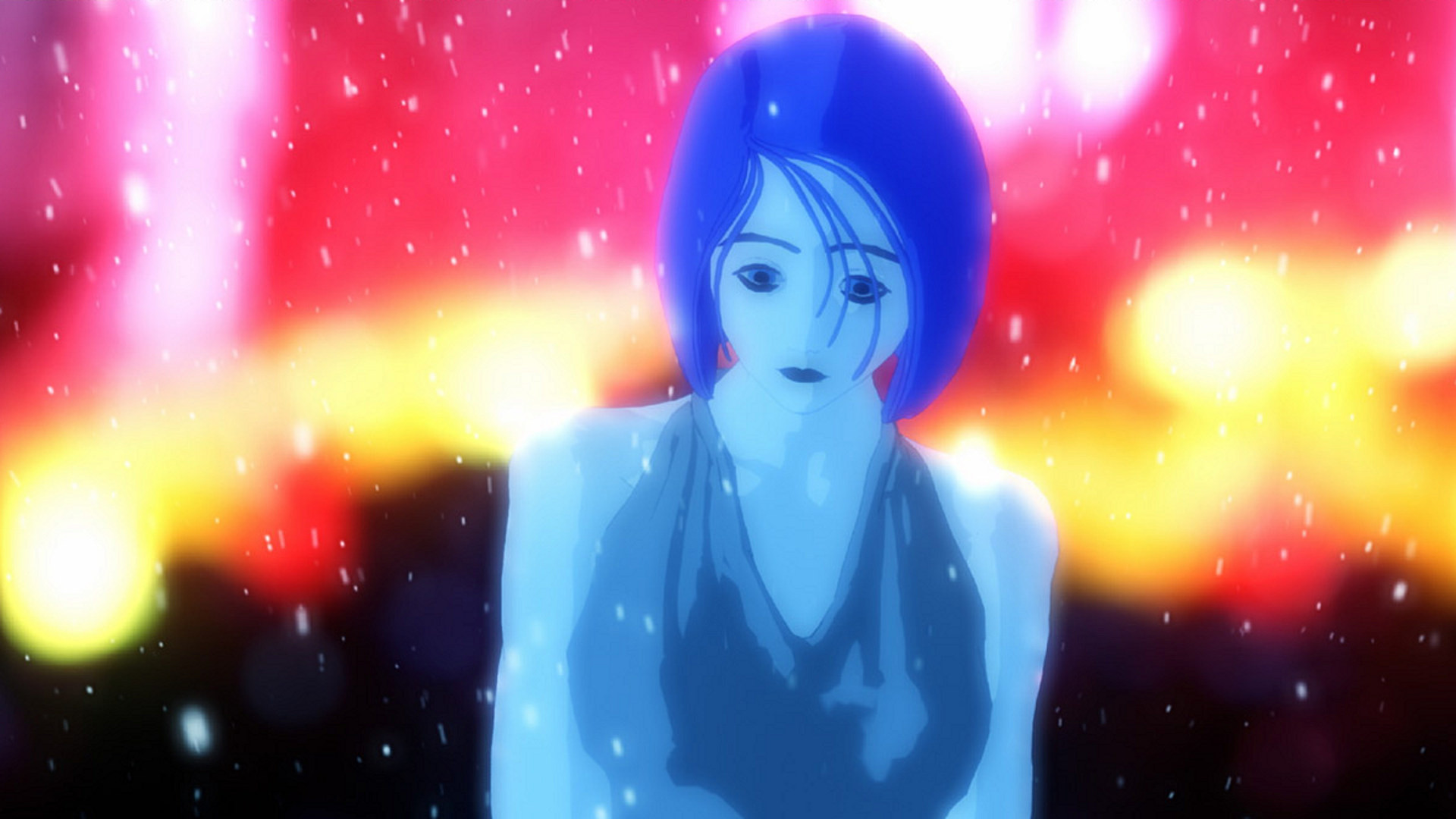

Advertised on the creator’s YouTube channel in 2006, premiering at Sundance in 2007, and then uploaded to that same YouTube channel a year later, We Are the Strange was one of our earliest signs that, for all its issues, YouTube really could be the ideal platform for a new generation of cinematic auteurs.

There’s some semblance of a story and cast of characters here, but overall, this feels much more like an extended art exhibition than a film – not that that’s a bad thing, especially if you’re keen on experimental cinema. But what really stands out about this film is how, in many ways, it feels like a convergence between pre- and post-internet age artistic influences. The film’s animation consists of a combination of stop motion, rough digital animation, and some very contemporary-looking pixel art. The result is…well, it feels kind of like the sort of film Jan Svankmajer would have made if he’d grown up in America during the height of the DeviantArt era.

There’s also the structure. M dot Strange cites David Lynch as an inspiration, and his influence on the film’s generally surreal tone and ambiguous plot is definitely there. However, the film’s structure and imagery also shows some clear influence from anime, particularly the flashy, stylised, action-heavy sort popular in the 90s and early 2000s (the film’s final sequence, in particular, feels like an extended tribute to mecha anime). This kind of weird crossover of artistic and cultural influences feels strangely symbolic – a sign, perhaps, of the fresh influences that the millennial generation of experimental filmmakers will showcase in the coming years.

We Are the Strange can be a challenging watch at times, between its overwhelming barrage of strange imagery and its deliberately obscure plotline; but it’s a fascinating early example of the changes that the advent of the internet has brought, and continues to bring, to the world of weird cinema.

8. Dead Mountaineer’s Hotel (1979)

Boris and Arkady Strugatsky may not exactly be household names in the West; but for enthusiasts of Soviet science fiction, they’re icons. Their work was deeply philosophical and introspective, and in spite of attempts by the government to censor it, it was widely read across the Soviet bloc, and had a lingering influence on contemporary intellectuals.

Dead Mountaineer’s Hotel (or “Hukkunud Alpinisti” hotell) is a lesser-known adaptation of one of their lesser-known books; but it’s a wonderful example of how quietly strange Soviet sci-fi films could be.

For one thing, it feels much more like a classic piece of detective fiction than a sci-fi film at first. We follow police inspector Peter Glebsky as he drives to a remote Alpine hotel, responding to a call for help. When he arrives, all seems well, and at first, he assumes the call was a false alarm. When an avalanche traps everyone at the hotel and one of the guests turns up dead, however, it becomes clear that things are not what they seem.

It takes a while for the sci-fi-driven weirdness to start seeping into this very And Then There Were None-type setup; and when they do, they’re very understated. However, they’re also the sort that, in the spirit of the Strugatsky brothers’ work, invite some serious introspection. The film as a whole certainly goes for the slow burn; but it plays both its sci-fi and detective fiction elements with sombre seriousness, and maintains a quietly ominous tone throughout. It’s quite unlike any detective or sci-fi film you’re likely to see come out of Hollywood, and while there are, perhaps, a couple issues with it (its 80 minute runtime, for instance, really doesn’t feel like enough time to properly introduce the rather broad cast of characters), it’s overall a very effective introduction to the general spirit of Soviet sci-fi, a greatly underappreciated subgenre in the West.

9. The Beast of Yucca Flats (1961)

If you’ve heard of this one at all, it’s likely because you saw the Satellite of Love crew mock it on Mystery Science Theater 3000 (and, let’s face it, even they couldn’t make it watchable). Some misguided folks have compared this to Plan 9 From Outer Space; but they couldn’t be more wrong. If Ed Wood is the Steven Spielberg of bad cinema, Coleman Francis (who directed this) is the Todd Solondz. His films are steeped in misery, bleakness, and an ingrained sense of nihilism.

Above all else, though, Beast of Yucca Flats is weird. Not weird in an artistic or experimental way, though; its weirdness comes more from the unique experience of watching how this film utterly fumbles the most basic elements of filmmaking at every turn. There’s a sort-of plot following a Soviet scientist (played by Tor Johnson, a 400-pound former pro-wrestler and Plan 9 alumni) getting caught in a nuclear blast in Nevada and turning into a shambling monster that strangles people; but for the most part, this film is about, well, a whole lot of nothing happening.

We spend ages watching static shots of Tor shambling his way across the sprawling desert or cars making their way down the highway, all while a narrator, voiced by Francis himself, rambles away about nothing in particular (there’s some stuff about how evil progress is and how there’s a flag on the moon – it’s impossible to follow) in a dull, droning monotone. The overall effect is simultaneously intensely boring and, somehow, strangely hypnotic; and the viewer is left with the impression of a film that became experimental and surreal purely by accident.

10. Fun In Balloon Land (1965)

Similar to The Beast of Yucca Flats, you’ve probably only heard of this one if you saw Rifftrax or The Cinema Snob making fun of it. And also similar to Beast, this is a prime example of a film becoming unintentionally weird purely through sheer incompetence.

This is only a “film” in the loosest sense of the term. Produced by a balloon company, the film consists mostly of footage of an old Thanksgiving balloon parade with an extremely overexcited female narrator desperately trying to make things seem interesting. The rest is some vague fairytale narrative about a sleeping curse being cast over a kingdom, told through grainy footage of a young boy wandering through a cavernous warehouse filled with crudely-painted balloon figures and dioramas.

The film might best be described as watching a succession of unlabelled VHS tapes you find gathering dust in your grandma’s attic – it’s simultaneously mind-numbingly boring and strangely unsettling. The incoherence is surreal and confusing, creepy and dreamlike, all completely by accident. There’s no fun to be had in watching it, but it can be quite a fascinating glimpse into the ugly underside of cinema in the 60s, and a reminder that zero-effort children’s entertainment long predates YouTube.