It has become common in recent years to look back on the ‘80s as one of Hollywood’s worst decades – a tawdry era of infantilization, golden age of the video shop, when Best Picture winners were elephantine bores, and the comic book blockbuster, that still dominates cinema forty years later, was born.

It is almost hard to imagine now that the simple, throwback pleasures of Star Wars were once seen as a fluke rather than a game-changer, but if you look at the top-grossing films of each year during the 80s, its influence is self-evident. Many of the decade’s most revered films were failures when first released, from classics like Once Upon a Time in America and The Thing, to perennial cult favourites like The King of Comedy, Blade Runner and Heathers. Patterns of success during this decade speak for themselves, whereas its failures are far less predictable, and, viewed today, generally more rewarding.

1. Cutter’s Way (1981)

A last hurrah for the paranoid thrillers of the Nixon era, this sun-drenched noir has yet to be accorded the status it deserves. Directed by Ivan Passer, and originally titled Cutter and Bone after Newton Thornburg’s source novel, it was left languishing in obscurity by a disinterested studio.

Cutter (John Heard), is a disabled, alcoholic Vietnam veteran, whose best friend Bone (Jeff Bridges), a part-time gigolo and nonchalant foil to his bitterness, is implicated in an unsolved murder. Cutter becomes obsessed with uncovering the true culprit, whom he believes to be a local oligarch. As they trawl ever deeper in search of intrigue, the supposed enemy’s guilt becomes increasingly clear to Cutter, but no less obscure to the audience. In the end, the criminal is necessarily brought to account, though the film dares to keep his exact crime ambiguous.

Beautifully photographed by Jordan Cronenweth, and with a brilliant performance from Lisa Eichhorn as Cutter’s depressive wife, the film is a quietly devastating coda to the string of existential mysteries that marked the previous decade, easily calling to mind the likes of Roman Polanski’s Chinatown or Robert Altman’s The Long Goodbye (whose co-star Nina Van Pallandt even makes a cameo appearance). Its confrontational despair was no longer considered fashionable, dooming its commercial prospects from the outset.

2. Day of the Dead (1985)

George A. Romero concluded his initial sequence of zombie horrors with this cautionary tale, in which a surviving pocket of humans, stuck in an underground bunker during the apocalypse, get on each others’ nerves. Lori Cardille stars as leader of the scientific faction, whose search for a cure to the plague is thwarted by its military cohabitants. After realizing a return to the past may not be worth it, she and her friends flee to an island and set up their own commune.

Envisioned by Romero as “the Gone with the Wind of zombie movies”, budgetary constraints forced him to create something more claustrophobic, and, probably, more intense. Whereas Dawn of the Dead (1978) was a satire of consumerism, this follow-up explores the dangers of anti-intellectualism, pitched to a level of hysteria. Save for some obnoxious overacting by the supporting cast, this is a complex and deceptively hopeful portrayal of the humanist struggle against nihilism.

The film’s innovative combination of gore and rage, without the humour of its contemporaries, was off-putting to audiences at the time, and it had a poor domestic run. In recent years it seems to have become fair game for the horror reboot cycle, demonstrating at least that it remains the most timely of the series, if not, arguably, the best.

3. Ishtar (1987)

Elaine May is one of New Hollywood’s most fascinating filmmakers, though she directed only four features. The last of these, Ishtar, remains one of cinema’s costliest flops, a reputation that continues to haunt it, despite growing admiration. Intended as an affectionate nod to the Bob Hope/Bing Crosby Road series, Warren Beatty and Dustin Hoffman play an odd couple pursuing their late-life dream of becoming pop stars, mutually delusional as to their lack of talent. Attempting to reach a gig in Morocco, they become embroiled in a CIA power play and get lost in the desert, but survive with their delusions still intact. The result is a droll but winsome satire on U.S. foreign policy and middle-age.

Released during a time when Hollywood was transitioning from the director-driven climate of the ‘70s to yuppy corporate governance, Ishtar became a victim of studio politics, from inside and out, as critics flocked to declare it ‘one the worst movies of the year’, then ‘one of the worst movies ever made.’ Although co-star Isabelle Adjani is sorely underused, looking at the film today, these reviews are pretty baffling, and proof that, in Hollywood, films that went vastly over budget were only a serious problem if women directed them. The reception may also have been milder had it starred comedy actors, rather than showing two of the world’s most famous leading men as vulnerable cartoons of egotism.

4. Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters (1985)

Paul Schrader’s hallucinatory biopic of Japanese author and activist Yukio Mishima is one of the decade’s most ravishingly stylized films, a polyphonic essay, vacillating between docudrama and hyperrealism, whilst keeping its controversial subject at a respectfully ambiguous distance.

The film begins as an account of the events leading up to Mishima’s death by seppuku in 1970, interspersed with episodes from his childhood, rendered elegantly in monochrome, and vignettes from several of his novels. Showcasing fantastical designs by Eiko Ishioka, these interludes serve as an interior world of psychosexual phantasy, their impressionistic high-artifice contrasting with the handheld grittiness of the outer world, where Mishima attempts an unsuccessful coup against the Japanese government. Given Schrader’s sharply indecisive use of form, the suicide is a fittingly destructive end.

Made little more than a decade after his death, the film was condemned in Japan, where Mishima’s ultraconservatism made him a ‘non-subject’. But with no big-name stars, and in subtitled Japanese, it was far from commercially viable for Hollywood, and its lack of box office was hardly surprising. That it was made at all is remarkable.

5. One from the Heart (1981)

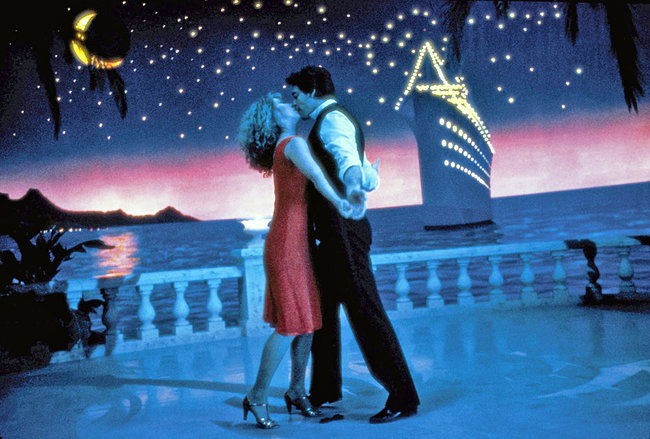

Having had perhaps the most artistically successful decade of any director in Hollywood history, Francis Ford Coppola made an inauspicious start to the ‘80s with this ill-timed attempt to revitalize the musical. Terri Garr and Frederic Forrest play an unglamorously normal couple in an ultra-stylized, twilight world. Fed up with each other, they have separate experiences in the company of exotic Raul Julia and gamine Nastassja Kinski, before ending up back where they seemingly belong in each other’s arms.

Aided by an eclectic score from Tom Waits and Crystal Gale, Coppola chose to build the Las Vegas setting entirely in the studio, fashioning a realm of adult make-believe with the same willful skill as Powell & Pressburger or Jean Renoir. The result is a dazzling return to the aesthetic of the Dream Factory.

Sadly, audiences during Reagan’s Recession had different escapist tastes to those of the Great Depression, and the film was ignored, plunging Coppola into financial difficulty for years to come. Despite this failure, its brash rejection of realism helped spearhead the cinéma du look movement in France.