In the year when the Best Film Oscar was given to a foreign-language movie for the first time, this list takes us around the world, to show how cinephiles have been discovering long-lost gems of world cinema throughout the decade.

1. Insiang (Lino Brocka, 1976)

Our first stop is the Philippines, where today one of the world’s greatest, if seldom seen, directors, Lav Diaz, is still churning out his epic sagas of the political repression and meagre resistance that took place under the Marcos regime. But the last few years has seen the re-emergence of a film-maker who worked during that time, and whose rebellious spirit has been a major influence on Diaz and other Filipino directors since. Lino Brocka is best-known for Manila In The Claws Of Neon (1975), a powerful saga of innocents lost in the big city, but its follow-up is arguably even more wrenching.

It tells the story of a young woman living in the riverside slums in close quarters with her bitter mother and the mother’s ne’er-do-well boyfriend, and how this claustrophobic situation spills over into rape and bloody revenge. Brocka evokes the volatility of this underclass milieu through his jagged editing, close-cropped framing, and aggressive sound design. But the film is also compassionate and strangely tender, building to an ending that is unashamedly melodramatic but where the most powerful emotions are unspoken.

2. Cairo Station (Youssef Chahine, 1958)

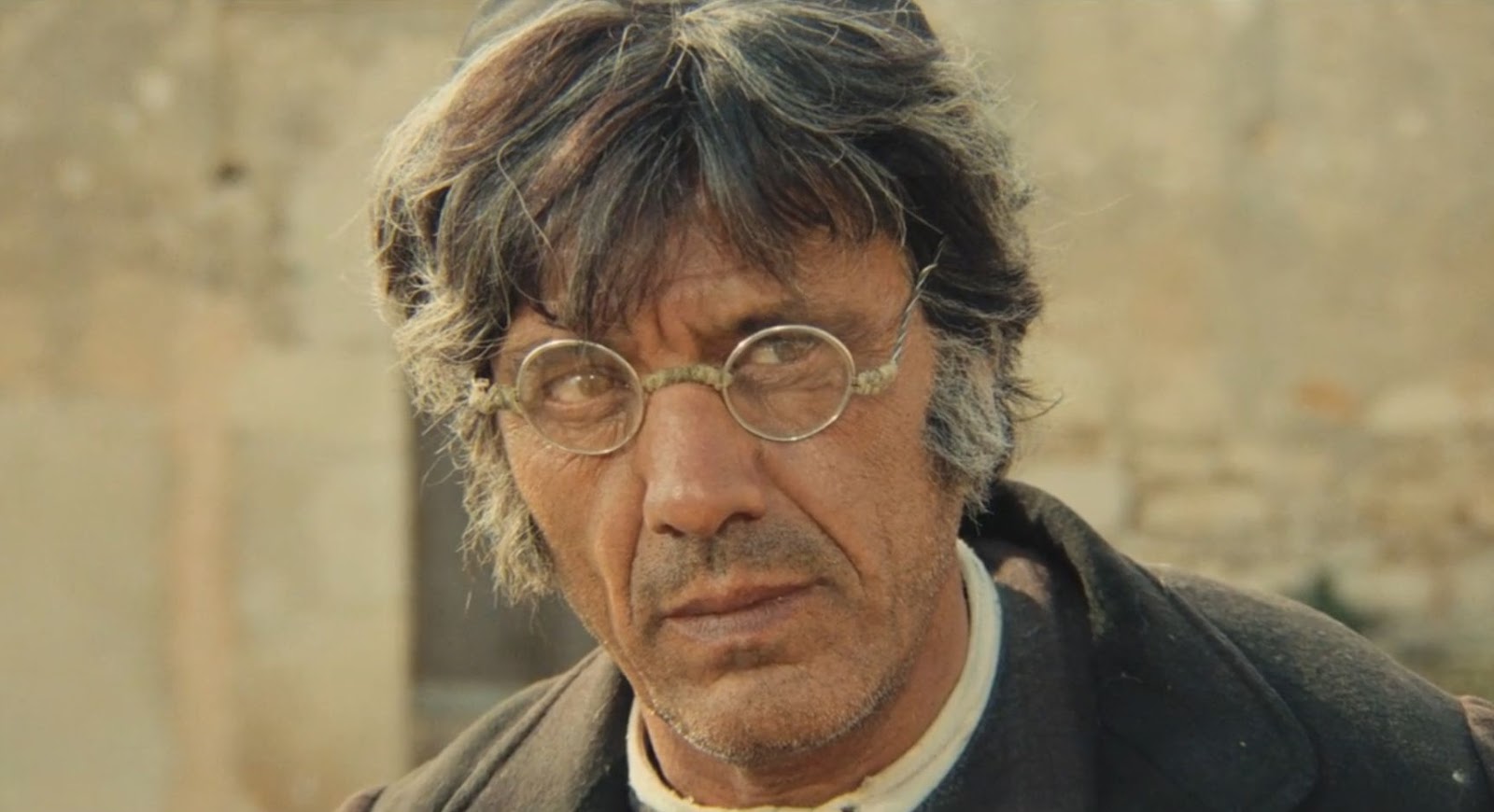

Another melodramatic powerhouse roiling with sexual and social tension is Egyptian director Youssef Chahine’s Cairo Station. Chahine himself plays a poor newspaper salesman plying his trade in the hustle and bustle of the capital’s train station, but who is tormented by his lust for Hannouma, one of the beautiful and fiery girls who peddle drinks to passengers.

These two protagonists anchor the story, but Chahine revels in the noise, colour and excitement of the passing crowds and provides a dizzying kaleidoscope of characters, from union workers warring over their respective territories to young lovers escaping for the day, all of which adds up to a compelling portrait of Egyptian society in general. The style is predominantly neo-realist but spiced with generous splashes of black humour and Hitchcockian tension.

3. Mr Thank You (Hiroshi Shimizu, 1936)

From trains to buses, and from the heaving metropolis to the gentler world of the remote seaside village, this time in Japan. Shimizu’s film is so light and breezy, it’s easy to ignore how original and groundbreaking it is, both in the context of Japanese cinema and in the way it broaches social issues.

The Mr Thank You of the title is the local bus driver, who transports customers from the little villages and towns nestling in the mountains to the distant capital, Tokyo, and who somehow helps each of his passengers along the way. They include a poor family en route to sell their daughter into marriage, a pompous salesman, and a brazen young woman, whose licentious behaviour seesaws between rude provocation and moral comment on the delusions of her fellow travellers. If the film has the whiff of didactic fable, that’s undercut by its constant humour and innocent affection for all the characters on the bus, the beauty of the location photography, and the sheer strangeness of its conception.

4. Kaos (Paolo and Vittorio Taviani, 1984)

A journey of a very different kind opens this film by the Taviani brothers: some peasants tie a tiny bell around the neck of a crow and it flutters off into the sky, soaring above the landscapes of Sicily. Set to Nicola Piovani’s haunting music score, the cruelty of this opening sequence evokes the position of the poet, trapped and forever driven by their obsession with beauty to seek out landscapes of the mind.

The poet in this case is Luigi Pirandello, four of whose stories make up this portmanteau film, the first three of which are based on folklore, the last an autobiographical tale involving an incident in the childhood of Pirandello’s mother, an incident which seems, by allusion, to magically link the other stories together. The fact that this film has lain neglected for so many years is a wonder in itself. It is not only the Tavianis’ best work, but one of the greatest examples of lyric cinema ever made.

5. Dainah La Metisse (Jean Gremillon, 1932)

Another journey, both literal and metaphorical, takes place in Gremillon’s fascinating early work, Dainah La Metisse, this time on a luxury cruise liner. On board is a black African magician and his ravishing mixed-race wife (la metisse of the title) who becomes a favourite both of the gentlemen in first class and the burly crew working the engines down below. When his wife is seemingly assaulted, the magician’s jealousy boils over.

Gremillon is chiefly known for his realist dramas of the 1940s, so the discovery of this gem came as a surprise, because it feels closer in style to German Expressionism, mixed with the austere, unearthly composition of Carl Dreyer. A particular highlight is the masked ball, in which the guests leer over the doomed couple in grotesque masks and the magic act appears almost supernatural in its effects. The film is also notable for its sympathy with a black lead character and the intelligence and honesty of its examination of colonial high society.