6. One False Move (Carl Franklin, 1992)

Carl Franklin’s debut is virtually built to be forgotten. It’s a quietly compelling crime picture, free of the excess gore and smirking nihilism that Tarantino disciples rattled off later that decade. Working off a script co-written by Billy Bob Thornton, Franklin understands the value of slowing things down to give a sense of place and an intimacy with the characters. A dirty little secret about the most successful noirs is that they are triumphs of atmosphere and character, rather than extravagant plot twists.

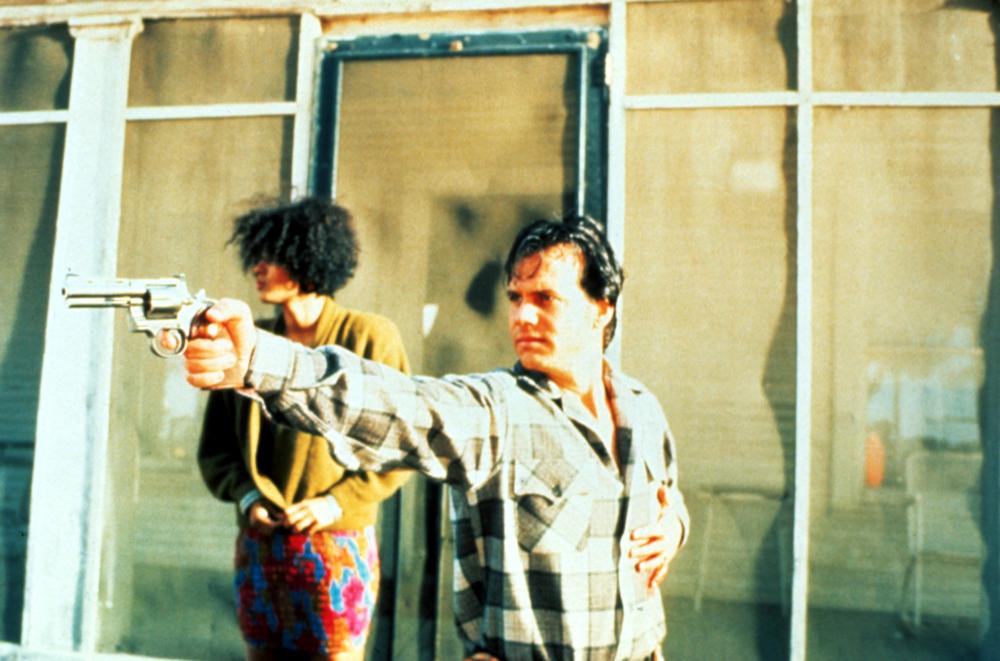

The movie begins with Ray (Billy Bob Thornton), Pluto (Michael Beach) and Fantasia (Cynda Williams) robbing some LA drug dealers and brutally killing the witnesses. As they go on the run, the cops quickly figure out that at least Fantasia is on her way to Star City, Arkansas with her share of the loot. So LA sends a pair of cops to that small town, presided over by Sheriff Dale Dixon (Bill Paxton).

Few movies have made better use of Paxton, who launched his career playing squealing morons in the likes of Aliens (1986). His gosh-golly sheriff is easy to mock, but as the movie unfolds, we see he’s not the butt of the joke, but rather the flawed heart of the movie. Franklin portrays the racial dynamics in new and interesting ways, and shows us a side of the South that audiences rarely see. It’s not so much reinventing genre conventions, so much as employing them to fully capture people that are usually ciphers in other films. Franklin would remain a stellar craftsman, although he kept producing movies too smart to shout about themselves.

7. Fearless (Peter Weir, 1993)

Peter Weir complicates the picture of Hollywood in the 1980s by taking unremarkable concepts and delivering mainstream hits like Witness (1985) and Dead Poets Society (1989). He gambled in content, but not in style, which is not how to be bandied about in “Conversations About Auteurs.” Even worse, his very best work tends to be forgotten, like Master & Commander: The Far Side of the World, and this picture.

Adapted by Rafael Yglesias from his own novel, Fearless finds Jeff Bridges surviving a plane crash, one of the most upsetting ever rendered onscreen. Because he helped several others escape to safety, he’s touted as hero, but the most surprising consequence is he’s no longer encumbered by fear of any kind. Rather than treating this as a superpower, the movie depicts how this makes him obnoxious, and even a bit cruel, to his wife (Isabella Rossellini), his children and his friends. With no need to lie or play along to get along, he becomes a kind of destructive force that is at once right, and deeply damaging.

Weir doesn’t stint in rendering the glories of a life without fear, but always returns to their costs. The movie builds beautifully to its own shattering climax that manages to be as life-affirming as it is horrifying. And Rosie Perez’s performance as young mother who lost her child on the flight is a career high that rightly snagged her an Oscar nomination. There simply has been nothing like it, before or since, and belongs beside It’s A Wonderful Life as a testament to how precious and fragile any life is.

8. Out of Sight (Steven Soderbergh, 1998)

Elmore Leonard novels seem built for the screen with punchy, natural dialogue, sharp, grounded twists and cooler than ice-cold heroes. But movie adaptations tended to drop the gags (Stick) or tone down the malevolence (Get Shorty) and certainly ignored the emotional baggage so many of his leads carried. Tarantino delivered one of his finest efforts, if not a hit, by adapting Rum Punch into Jackie Brown (1995), but by then he had so fully integrated Leonard into his own style, that remains very much his own joint.

Steven Soderbergh is a more natural chameleon, and in 1998, he was still struggling to regain the perch he enjoyed after his debut, Sex, Lies & Videotape (1989). Here, he had a world class script from Scott Frank that deftly captured the full range of Leonard’s work. Out of Sight concerns a talented thief (George Clooney) falling for the US Marshal (Jennifer Lopez) out to get him. Don Cheadle is but one of an all-star cast, but his turn as a malicious and ridiculous sociopath is one of the best of its kind.

Wildly hilarious and just as nerve-wracking, perhaps its greatest accomplishment is the romance between Clooney and Lopez, with both at the top of their game as actors, and movie stars. Their rendezvous in Detroit is rendered for maximum heat and glamour, thanks to the time lapse editing by Anne Coates, rejiggering their cat and mouse seduction into a tone poem. It’s rare to find romance of this wattage in any era, but especially now when so few movies even concern themselves with people falling in love. The greatest mystery was its meager box office haul, but by then adults might have already begun to assume the big screen no longer offered grown-up pleasures like these.

9. The Straight Story (David Lynch, 1999)

David Lynch’s Disney film sounds like a lousy comedy sketch, but in 1999, he did in fact direct a G-rated film based on the true story of Alvin Straight, who rode his lawn mower from Iowa to Wisconsin to visit his ailing brother. The result was one of the greatest feats in a career full of them, a movie far more moving and honest than any of the comforting fairy tales that built Walt’s cultural juggernaut.

Here, Alvin Straight (Richard Farnsworth) is neither knight nor folksy do-gooder. He’s a WWII vet haunted by his regrets and when he does share his wisdom, it’s laced with a sense he learned such things from his own mistakes. Lynch never taps his brand of dream logic here, but he still eyes Alvin’s Midwest world through his oddball lens, which only seems to ground the characters. Real people are this strange. But as Alvin makes his way down the highway on his souped-up mower, his obstacles are engine trouble and old age, not some psychotic pimp.

It plays closer to a lost Willie Nelson song, using a simple story line to grapple with the thorniest parts of being alive, with grace and good humor. It may lack Lynch’s mysterious blend of sex, violence and despair, but this is most certainly an adult picture. No teenager sees themselves in Alvin Straight’s wrinkled visage, or understands just how much forgiveness and reconciliation will come to matter. Lynch casts another living legend as the brother, and the two actors, when they finally meet, remains one of the most profound moments Lynch ever produced, perhaps all the more so for coming from the fellow responsible for Blue Velvet.

10. A Most Violent Year (JC Chandor, 2014)

The energy of the most gangster pictures comes from the thrill of watching them get away with it, at least for the first hour. Gangsters embody the dark romance of capitalism, where ambition is unbound by law or decorum. There may be an honor code, but it’s the best kind: enough to feel superior, but never enough to get in the way of what they want. A Most Violent Year reverses this polarity, by following someone trying desperately to stay on the straight and narrow, when cutting ethical corners would make life much easier.

Set in the New York circa 1981, the movie has Oscar Isaac playing a middle-class owner of an oil transportation company that finds his trucks hijacked, and suspects his competitors are responsible. The DA already assumes Isaac is involved in shady dealings, so Isaac feels committed to staying above the fray, a stance that his wife, played by Jessica Chastain as Lady Macbeth by way of the Queensborough bridge, doesn’t support. She thinks he should be plotting retribution. As the pressure mounts, Isaac can’t help but take less than legal means to protect himself, which only further risks running afoul of the authorities, all without the profits from an actual criminal enterprise.

By virtue of its time period, and its bone-dry procedural tone, critics nodded at its competence, but dismissed it as merely an homage to the kind of crime dramas Sidney Lumet mastered. It’s more than that. Rather than viewing the gangster ethos as some kind of the perversion of capitalism, we watch at how the free market forces people to act like gangsters. Michael Moore could hardly muster a better indictment of the American way, and JC Chandor does so without the smirk and speechifying. Instead, he does plenty more by merely charting the demise of the one man’s best intentions in a broken system.