20. The Lower Depths (1957)

Kurosawa brings Maxim Gorky’s early 20th century play to the big screen with tremendous style. The film’s dramatic origins are apparent in its confined settings, with much of the story taking place in a single room, and Kurosawa applies his cinematic gifts to the material through creative blocking and dynamic camerawork — knowing at every second where place his camera and how to coordinate everything within its field of view.

All of the characters are sharply defined, the actors consummately matched to their roles. Most enjoyable is Bokuzen Hidari as a quirky outsider visiting a community torn apart by lust and hypocrisy. A much better “life in the slums” film than the earlier mentioned Dodesukaden.

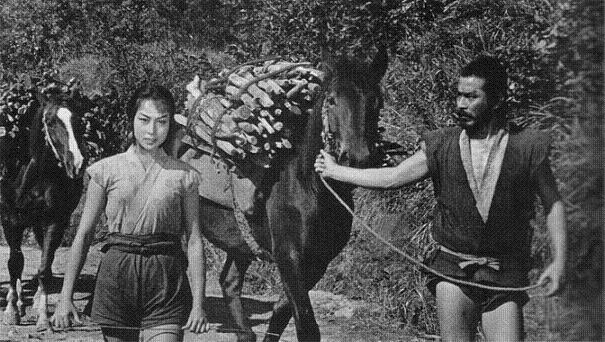

19. The Hidden Fortress (1958)

Much has been written about this film’s influence on the original Star Wars (the story being told primarily through a pair of comic side characters, a quest to save a princess during a time of war), and like the film it helped inspire, The Hidden Fortress is tremendous, lightweight entertainment.

In casting the part of the princess, Kurosawa put out a nationwide call to find a woman “with a fresh and princess-like dignity” who had “the intensity of a samurai’s daughter.” Twenty-year-old Misa Uehara had no previous acting experience, but that’s not evident in her effortlessly strong performance — in particular, the “miraculous” eyes Kurosawa adored in her are used to great effect.

18. One Wonderful Sunday (1947)

That Kurosawa could so effortlessly weave between scenes of whimsy, scenes of despair, scenes of bliss, and moments of breaking the fourth wall — all in one film — and still maintain a cohesive narrative is a true testament to his strengths as a storyteller. One Wonderful Sunday follows a young, impoverished couple who meet every Sunday in Tokyo and try to find some happiness despite the fact that they have very little money. While the woman insists on remaining upbeat and positive, her partner sulks around dejectedly, his few moments of happiness almost routinely spoiled by the harsh realities of poverty in postwar Japan.

At the time of One Wonderful Sunday, Toho Studios had lost most of its established box office talent due to a labor union strike, necessitating the casting of less famous newcomers. Fortunately, Isao Numasaki and Chieko Nakakita prove to be most worthy successors, as they completely sell the illusion of a couple who love each other and who continue to love each other in spite of their different views and the hardships they must endure.

17. Throne of Blood (1957)

Shakespeare’s Macbeth transposed to feudal Japan and enacted very much in the manner of a Noh play. Kurosawa made a few adjustments to his shooting script while filming, such as adding a creepy sequence of two horsemen struggling to find their way out of a fogbank and making the climactic death of the film’s protagonist even more disturbing than it seemed on paper.

16. Rhapsody in August (1991)

Kurosawa once said that before he could begin working on a film, he needed “a feeling about something, a feeling that it can become a movie, whether it’s a novel or anything else.” In the case of Rhapsody in August, he read Kiyoko Murata’s source novel while making Dreams and was particularly taken with a scene in which a group of kids chased after their grandmother in the rain. “I liked that scene very much,” Kurosawa recalled. “And I thought the scene would work wonderfully in a movie.”

Rhapsody in August is notable for featuring Richard Gere in a supporting role, and above all, it’s a thoughtful and elegant movie about generations looking back on one of the darkest and most controversial chapters in Japanese history. Gere plays a half-Japanese nephew to a woman who lost her husband in the bombing of Nagasaki — their interactions observed by the old woman’s grandchildren, who obviously are too young to have experienced the horrors of the bombing but who nonetheless regard its legacy and social impact from their own perspective.

15. Dersu Uzala (1975)

A major comeback after the failure of Dodesukaden five years earlier, this Russian language gem marked the dawn of a new phase in Kurosawa’s career. A good majority of the director’s films moving forward would focus on men beset by old age, drama stemming from their struggles to get along in a world completely unlike the one they’d known.

Kurosawa had originally wanted to make this film in the 1930s, but it’s strangely fitting that it didn’t come to fruition until much later. The eponymous character in Dersu Uzala is an elderly trapper plagued by poor health, who ends up trying to integrate into a “society” he knows little about. By 1975, Kurosawa was not only in his upper years himself (having recently turned 65), but his career had been hindered by a variety of setbacks. The Japanese film industry was steadily falling apart and studios were reluctant to cough up the money necessary to manifest his vision; consequently, he made movies less often and frequently turned to admirers overseas for co-financing (in this case, he made a movie outside of Japan).

The times which had allowed him to crank out his masterpieces on an annual basis had passed, never to return. So in a sense, Kurosawa was very much like Dersu: a wise old man fighting an uphill battle in changing times.

14. Ikiru (1952)

In making Ikiru, one of the most moving films of all time, Kurosawa took a chance by giving the leading role to Takashi Shimura, an actor who, although widely respected, was hardly a box office name. The gamble paid off, as the film became a financial success and granted Shimura further international acclaim, the New York Times calling him the greatest actor in the world.

Shimura is perfectly cast as a middle-aged man stuck in the endless rigors of Japanese bureaucracy (where change and individual accomplishment is essentially forbidden) until he discovers he’s terminally ill with stomach cancer (the number one cause of death in Japan at the time). At first unsure what to do with the time he has left, Shimura later becomes inspired to find something important he can accomplish, something meaningful he can do with his life. And the venue in which he chooses to enact his mission of self-fulfillment is the same bureaucratic office where, up until this point, he’d accomplished nothing.

This incredible film is both a moving portrait of an individual’s drive as well as a savage critique of the shortcomings (and hypocrisy) of Japanese bureaucracy.

13. Drunken Angel (1948)

In writing Drunken Angel, Kurosawa and co-screenwriter Keinosuke Uekasa encountered a conundrum: the movie’s plot concerned the relationship between a tubercular yakuza and the noble doctor trying to treat him, but they could only write one of the characters to satisfying effect. The yakuza turned out solid in every draft, but something was off about the doctor. Kurosawa eventually realized by making the doctor such an angelic, good-hearted person, the story became too “black and white,” too much about obvious good versus obvious evil. To correct this, Kurosawa sagaciously changed the doctor into a vulgar alcoholic, giving him shades of gray and making his dynamic with the yakuza more interesting; now the two men had traits in common.

This stroke of genius helped elevate Drunken Angel into a superb drama about characters who are byproducts of their environment — a community full of dilapidated neighborhoods, disease, and organized crime (all factors which proliferated in Japan after the war). Kurosawa’s use of the environment for symbolism is astonishing. In one great moment, the yakuza, contemplating putting an end to his ways, stands before the murky waters of a sump with a flower in his hand, the flower symbolizing his chance for a new, better life. Upon deciding to go back to his old ways, he throws the flower into the sump, Kurosawa’s camera watching somberly.

12. The Bad Sleep Well (1960)

Kurosawa is most widely known for his samurai pictures and period pieces, but he made several powerful movies set in the modern age, dealing with contemporary issues. In the case of The Bad Sleep Well, he targets corporate corruption. As Kurosawa regularly tackled new subjects, he gave new opportunities to his actors. Here, Toshiro Mifune is cast not as an abrasive, over-the-top ruffian; this time, he’s cold and calculating.

11. No Regrets for Our Youth (1946)

This postwar melodrama was precisely the sort of film which appealed to the American censors controlling Japan’s film industry after World War II: a movie featuring individuals taking a stand against militarism, with a free-minded woman at the center of the narrative. It’s also the first truly special film in Kurosawa’s career.

Leading actress Setsuko Hara delivers one of her absolute best performances as a young woman searching for something precious to her while her country goes through immense change over a period of twelve years. Though she associates with politically minded people, her principal goal — like many Kurosawa protagonists — is to find her own individuality, her own sense of purpose, her own sense of fulfillment. Looking back on the movie, Kurosawa said: “I believed [at the time] that it was necessary to respect the ‘self’ for Japan to be reborn. I still believe it. I depicted a woman who maintained such a sense of ‘self.’”