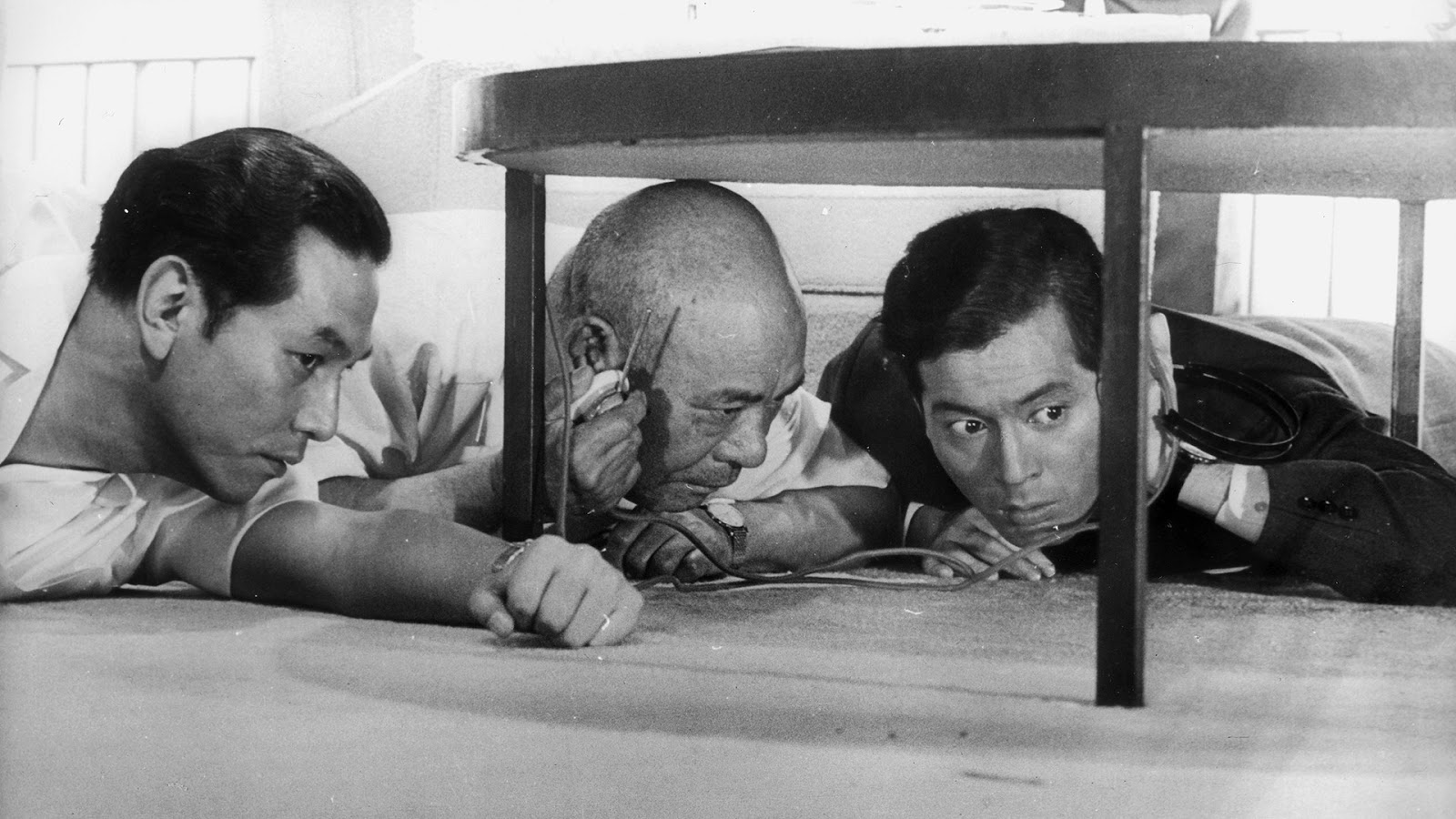

10. Red Beard (1965)

Kurosawa’s final black-and-white picture, and the last film he made with Toshiro Mifune. Red Beard required nearly two years to make and production was hindered by a great amount of on-set tension — all of which proved to be well worth the trouble, as the final results constitute one of the director’s finest achievements. Yuzo Kayama, who had a supporting role in Sanjuro, takes the stage opposite Mifune and does so with tremendous gravitas. Also great is Kyoko Kagawa, cast against type as a psychotic patient, whose standout scene is so chillingly effective one almost wishes there were an entire movie about her.

9. The Idiot (1951)

What prevents The Idiot from cracking the top five on this list is the unfortunate fact that, like Sanshiro Sugata, a sizable portion of it has been lost. Kurosawa’s original cut was 265 minutes long, but the most extant version today only clocks in at 166 minutes, necessitating the use of intertitles to explain parts of the story to the audience. It’s a shame, for even in its incomplete version, this adaptation of Fyodor Dostoevsky’s novel is one of the most unusual and intoxicatingly watchable films in Kurosawa’s oeuvre.

Kurosawa shifts the novel’s setting to Japan’s northernmost island of Hokkaido (one of the more “westernized” regions of Japan), composer Fumio Hayasaka delivering a very “Russian” score. It also features what is unquestionably the single most impressive cast in any Kurosawa film. The majority of Kurosawa’s “stock company” appears here, along with a few faces new to his work — such as Chieko Higashiyama of Tokyo Story fame. Most interesting is Setsuko Hara, sweet and lovable in No Regrets for Our Youth, cast entirely against type as an aggressive, temperamental woman molded by the cruelty of the world around her. (Her all black wardrobe was reportedly modeled after María Casares’ costumes in Jean Cocteau’s Orpheus.)

Kurosawa made The Idiot for Shochiku and upon returning to the studio forty years later to make Rhapsody in August searched their vaults for his film’s missing 100 minutes of footage. Alas, the scenes remain lost to this day.

8. The Quiet Duel (1949)

After a labor union strike at Toho Studios in 1948, Kurosawa started shopping his talents to other film companies. For Daiei, he made this tense, thoughtful drama about a doctor who accidentally contracts syphilis while operating on a sick patient during the war. When he returns home, he tries desperately to keep his disease a secret, especially from his fiancée, whom he chooses not to marry so she does not become sick herself — shackling his desires and needs for the good of those around him.

The Quiet Duel also features one of Kurosawa’s most interesting female characters: a cynical nurse played by Noriko Sengoku who’s initially leery of the doctor but later comes to respect him after learning his secret and witnessing his devotion to others.

7. Stray Dog (1949)

An extraordinary masterpiece about a soldier-turned-detective whose pistol is stolen by a pickpocket. Realizing his gun has likely been sold on the black market and is now being used to rob and kill people throughout Tokyo, he sets out on a personal mission to recover it. Eventually, with help from a senior detective, he learns the man using his gun is also a former soldier — one who failed to reintegrate into society and subsequently went off the deep end.

Like a good many of Kurosawa’s immediate postwar films, the director uses genre framework for what might seem to be a typical entertainment film and makes poignant observations about the times in which he lived. Besides the depiction of two soldiers who went down different paths, Kurosawa showcases the extreme poverty present in postwar Japan. There’re also some clever jabs at the occupation’s attempt to “democratize” Japan. Example: one criminal threatens to sue the detectives for following her, abusing a “western” practice reintroduced to Japan to get away with her criminal activities.

6. Kagemusha (1980)

Kagemusha is one of Kurosawa’s most historically interesting films, for a number of reasons. First of all, it emerged through what might’ve been the single most frustrating shoot of the director’s career. Kurosawa had written the script with Zatoichi star Shintaro Katsu in mind for the leading role; Katsu accepted, but the two had a falling out on the first day of shooting and the actor ended up being replaced with Tatsuya Nakadai.

Kagemusha was slated to be photographed by Kazuo Miyagawa, who had previously shot Rashomon and Yojimbo for Kurosawa (not to mention Ugetsu for Kenji Mizoguchi and Floating Weeds for Yasujiro Ozu); unfortunately, Miyagawa ultimately had to stay on only as a creative consultant due to sudden health complications. Typhoons shut down production for a number of days, at a cost of several thousand dollars a day. That the film turned out as well as it did under these circumstances is truly remarkable.

Kagemusha is also unique for its themes of conformity. Many of Kurosawa’s past ventures had been about individuals standing against the system; here was a movie about a rebellious man conforming to the system. A condemned thief is chosen to serve as a double for a warlord. When the warlord is killed by an enemy sniper, he assumes the dead man’s responsibilities and, in the process, comes to revere the warlord’s legacy and is emotionally indoctrinated into the feudal system.

Kagemusha is also Kurosawa’s most physically beautiful film, teeming with a lush color palette. The director’s use of color had come a long way in the ten years since Dodesukaden.

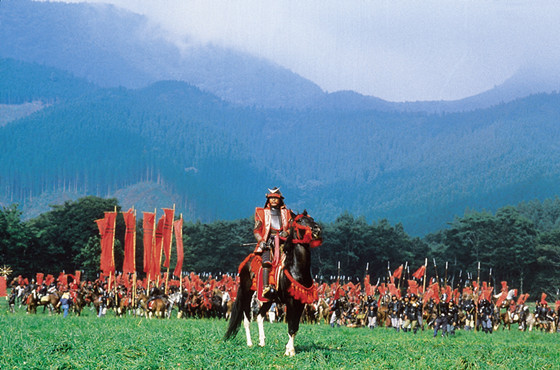

5. Ran (1985)

In the opening scene of Ran, a warlord named Hidetora Ichimonji chases down and slaughters a wild boar. Just when his bow is drawn and he’s ready to take the shot, the film cuts to its main title card, sparing us the actual moment in which the poor animal is killed. It is one of the few moments of mercy Kurosawa grants his audience in what is without a doubt his most disturbing and gruesome film.

Drawing inspiration from Shakespeare’s King Lear, Kurosawa returns to the subject of an old man in changing times. Ichimonji has lived a life of war and bloodshed and with his sons now taking over — and turning against him — his past has come back to haunt him. The horrors Ichimonji experiences — watching his men slaughtered, being banished from his own kingdom — very much mirror the cruelty he inflicted upon others when he was younger, except the violence is now geared toward him.

In writing the famous castle attack scene, Kurosawa specified the scene would play with “no real sounds” and that the music superimposed would be “like the Buddha’s heart, measured in beats of profound anguish, the chanting of a melody full of sorrow that begins like sobbing and rises gradually as it is repeated, like karmic cycles, then finally sounds like the wailing of countless Buddhas.” He offered no solution to the question of why men continued to kill each other over the generations, instead presenting acts of violence as horrifying and dehumanizing.

4. Yojimbo (1961)

Perhaps the most purely entertaining film in Kurosawa’s oeuvre and a counterpoint to Ran in terms of how it depicts violence. Toshiro Mifune’s laconic ronin wades through the villains of a corrupt town, often murmuring a joke in the wake of a kill. (After killing three men and lopping off the arm of a fourth, he tells the town carpenter to prepare three coffins, pauses, and then says four might be necessary once the maimed man bleeds to death.) None of his victims are made out to be sympathetic, and the movie never pretends to be “realistic” and is joyfully (and intentionally) funny.

And let it be said that Masaru Sato’s score is about as bouncy and memorable as they come.

3. High and Low (1963)

In the hands of another director, High and Low might’ve been a good genre film (a solid police procedural entertainment, if you will) but under Kurosawa’s care, it becomes one of the most thoughtful motion pictures of the 1960s.

Kurosawa uses genre framework (a kidnapper targets the son of a wealthy businessman) to raise moral dilemmas and offer poignant social commentary. A friend of the rich man’s son is kidnapped by mistake, but the criminal insists the businessman still pay the ransom or else place responsibility for the child’s death on his hands. Once the police become involved, the movie starts delving into the dark underbelly of Tokyo and uncovering the social ills affecting the less-well-off in postwar Japan. High and Low is as technically perfect as they come, and the final shot of this picture ranks with the most haunting endings in cinema history.

2. Rashomon (1950)

Working with two short stories by the pessimistic author Ryunosuke Akutagawa, Kurosawa tells the story of a murder in the forest and how the various parties involve offer their own versions of what happened, in the process exploring the relative nature of truth and man’s reluctance to be honest even with himself.

Two years after it achieved impressive box office results in Japan, Rashomon appeared at the Venice International Film Festival (unbeknown to Kurosawa, who was filming The Idiot when it was submitted) and promptly left its mark on the cinema landscape. Daiei’s studio boss Masaichi Nagata, who had been skeptical of the production, subsequently took credit for its acclaim and brilliance, but history continues to acknowledge it was Kurosawa, his screenwriter Shinobu Hashimoto, and the marvelous camerawork by Kazuo Miyagawa that made this film into what it is.

1. Seven Samurai (1954)

To place Seven Samurai at the top of any list about Kurosawa may seem routine, but this remarkable film deserves every ounce of praise it’s received and then some. Seven Samurai runs 207 minutes in length and never seems slow as it uses every frame to develop its characters, build tension, and deepen its thoughtful commentaries on class divide.

Kurosawa’s direction is thoroughly astonishing, especially his attention to detail. He spends so much time exploring the village and identifying how the warriors intend to fight the bandits threatening them that, by the time the battles are underway, we know the environment as well as the characters do. And since the characters are so wonderfully fleshed out, there is genuine rooting interest in seeing the heroes emerge victorious — as well as sympathy whenever someone loses their life in battle.

One could write about Seven Samurai for pages and never run out of things to say, but this endlessly fascinating film deserves its reputation as one of the landmarks of 20th century art.