4. Road to Perdition (2002)

A stylistic departure from the gangster films of the 90s (Goodfellas, Casino, Carlito’s Way, Miller’s Crossing et al), Road to Perdition plays more like Clint Eastwood’s Unforgiven – a revenge film with a heart. Mendes’ mob film works best when it is working on a personal level where a delicate piano duet or a small moment between father and son driving a car has a deeper, lasting effect. The action is swift and clinical, here, but it is the slow and intimate moments around the action that makes this gangster film more subdued.

Tom Hanks plays the hard-faced hitman, Michael Sullivan Sr., a son of sorts to mob kingpin John Rooney (Paul Newman). At first stern and cold towards his children, he swiftly turns his attention to saving his son and steering him from a similar gangster fate when he is a witness to one of Sullivan’s jobs. Now on the run from Rooney’s biological son, Connor (Daniel Craig), and sadistic photographer turned assassin, Maguire (Jude Law), Sullivan finds a way to balance reconnecting with his son with enacting revenge against those who have blown his world apart.

Occasionally sentimental and occasionally over-reliant on voice-over narration, Mendes has still managed to somewhat turn the gangster film on its head, again imbuing it with a pathos and spirit (seemingly a staple throughout all of his work).

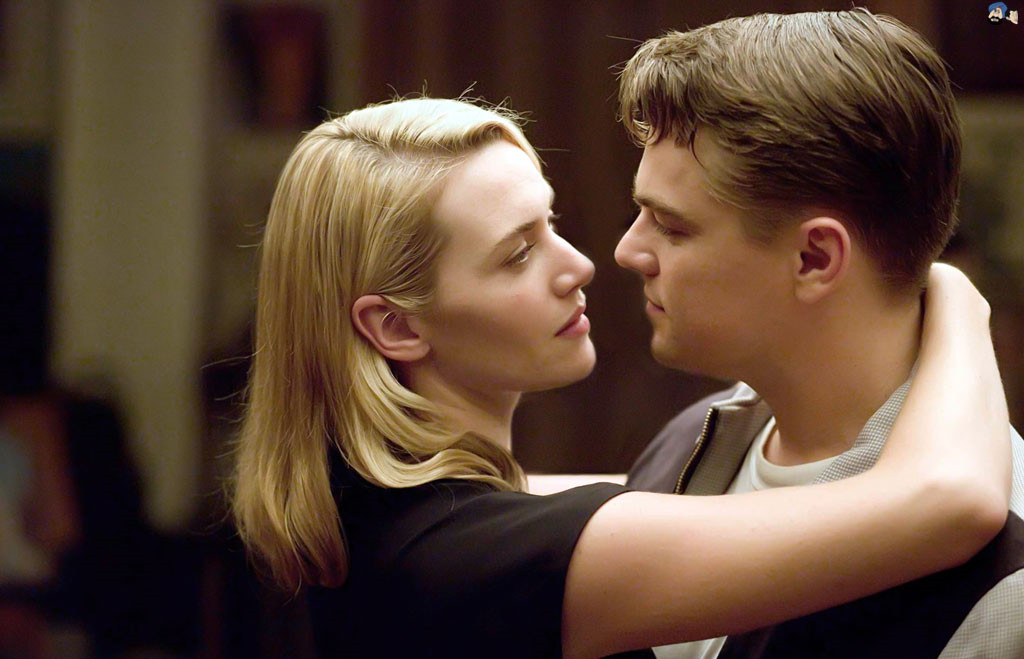

3. Revolutionary Road (2008)

Almost ten years after American Beauty, Mendes once again tackled American suburbia with Revolutionary Road, an adaptation of Richard Yates’ book of the same name. On the surface the Whealers (Kate Winslet and Leonardo DiCaprio) are the perfect couple: they are young, fresh, ambitious, and looking to settle into the perfect American family lifestyle, in the perfect picket fenced home.

Under the surface, though, things are not quite right. April is failing at her ambition on becoming an actress, Frank is stuck doing a job he does not want, and both are engaging in affairs – with neither really giving a damn. What gives both of them hope is a spontaneous plan to move to Paris and start again among a new city, culture, and way of life, leaving behind the “hopeless emptiness” of their sterile American lives.

What ensues is a beautiful tension between fear and love. Frank fears losing his chance at promotion but loves his wife, he fears failing in Paris but loves the spontaneity of the idea; April fears having another child but loves her children, she fears for her marriage but also wants to save it. This causes an internal conflict that is constantly playing on their minds resulting in Frank’s decision to stay in America after the persistent opinions from those around him.

Both of their internal frustrations and external failings to conform and achieve a better, more fruitful lifestyle here portrays the tattered remnants of the American Dream. Set in the 1950s, Mendes carves a critique on the desire to cling to safety and comfort.

2. Skyfall (2012)

Much like in Spectre, James Bond (again played brilliantly by Daniel Craig) is still reeling the effects of the previous film. After being accidentally shot, Bond uses his presumed death as a means of escaping his espionage lifestyle and replaces it with alcohol and solitude, regret and grievance. As Bond is progressively plagued by past traumas, M (Judi Dench) has to deal with her own wounds as her past is manifested in the elusive Raoul Silva (played menacingly by Javier Bardem) – a facially disfigured cyberterrorist hell-bent on enacting revenge on M, thus scarring the Double O programme altogether. Once again there is a foe to fight and an organisation to save but without the sharpshooting, slick Bond to do it.

Silva (and Bardem) are excellent here whereby his deep rooted connection to M separates him from the usual Bond villain caricature; Silva is not evil for evil’s sake but is driven by past conflict and injustice thus imbuing the role with a sympathetic edge that other Bond villains lack. Silva also, like Bond, lets his past traumas get the better of him as he hesitates when facing M which ultimately underpins his evil motives with a very un-villain like uncertainty.

Bond’s haywire behaviour at the beginning of the film (a trait that never really leaves him in Spectre either) parallels nicely with Silva’s own actions. He is always acting on a knife edge, here, and one push too many could spiral Bond’s trajectory along a similar path to Silva’s. The two are never too far apart which creates a tension that plays out brilliantly throughout Skyfall and marked Mendes’ first entry into the Bond franchise as a fresh and intelligent piece of storytelling.

The best Bond film? Arguably.

1. American Beauty (1999)

Mendes’ debut feature saw him win five Oscars (including Best Picture and Best Director) at the Academy Awards making his narrow miss this year seem less of a blow. The film is a beautiful synergy of ensemble cast, smart narrative devices, and a balance of humour and tragedy. It is Mendes’ first critique of American suburban life, choosing here to leave no one out of view: the surplus worker, the ambitious housewife (Annette Bening), the discontented daughter (Thora Birch), the abusive father (Chris Cooper), the nihilistic son (Wes Bentley).

Despite the facade of rose bushes, Lynch-esque picket fences, and automatic garages, everyone and everything is in breakdown by trying to live up to the life they all believe they should be living. Only Lester Burnham (played magnificently by Kevin Spacey) is privy to it – “in a way, I am dead already” he proclaims.

American Beauty follows Lester’s realisation as he, under the influence of pot and the adrenaline of quitting his job, starts to live life on his own terms. This is the films first beauty: Lester’s “no shits given” attitude to life that breaks the usual suburban mould. The second lies in his daughter’s best friend whose cheerleader antics and flirtatious behaviour take hold of Lester and is the driving force that sparks the revitalisation of Lester’s love for life (despite how delusional and disturbing it all is).

The third, and possibly truest, comes from Ricky Fitts’ observation of the world around him. Mostly an array of absurd, voyeuristic video recordings of his neighbours but occasionally beautiful videos of plastic bags floating in the wind (or the beauty of everyday life), Ricky’s odd and sometimes crazy reflection of the world culminates in his relationship with Jane Burnham – her only respite from her own sense of hopeless emptiness.

A triumph in storytelling, Mendes marked his prowess from the very start and kick-started his eclectic filmmaking career in brave and ambitious style.