5. Fanny and Alexander (Ingmar Bergman, 1983)

Often considered one of the greatest films in modern cinema (and undeniably one of Bergman’s greatest too), Fanny and Alexander won for Best Foreign Language Film at the 56th Academy Awards, a nomination that ultimately ruled it out from winning in the Best Film category – of which it would have had a great chance.

Fanny and Alexander is an epic historical drama that follows the titular siblings (played by Pernilla Allwin and Bertil Guve) and their family living in Uppsala. It is a semi-autobiographical tale with many of the characters based off of Bergman’s own family members. An outward projection of the inner workings of Bergman’s mind and imagination, the film tackles ideas around family conflict, religion, and mixes reality with magic all witnessed through the guise of a child’s memory.

Bergman won back-to-back Best Foreign Language Film Oscar’s with The Virgin Spring (1960) and Through a Glass Darkly (1961). But Fanny and Alexander feels like an amalgamation of Bergman’s life work and seems an apt and worthy addition here.

4. Amour (Michael Haneke, 2012)

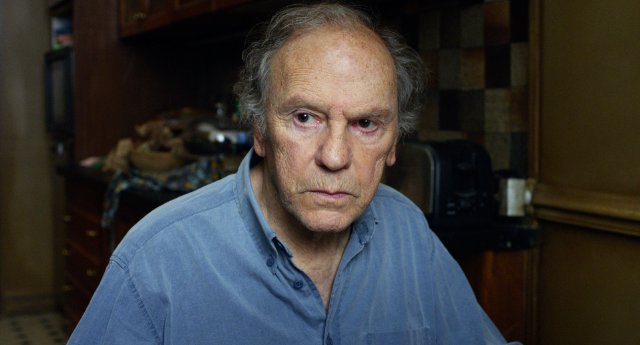

Haneke has always been well-known for making gruelling and difficult work, focusing largely on characters who feel displaced from the current world that they live in. His slow narrative style places the audience into a false sense of comfort whereby he builds his films into a sudden and often brutal climax. On the surface, Amour seems to take a more tender approach by telling the story of a relationship between two long-lasting lovers. While it definitely explores love and endurance, Haneke still manages to underpin his work, though, with his signature harsh and punishing style.

Following the lives of Georges (Jean-Louis Trintignant) and Anne Laurent (Emmanuelle Riva) after Anne has had a stroke and lost the ability to move half of her body, we meander through the struggles each character goes through – both physical and psychological. For the most part, Georges is an amiable and hardworking partner, helping Anne through every excruciating moment. But as the pressure starts to build and the strain of tending for his wife starts to get heavier, he occasionally and abruptly starts to snap. Anne, on the other hand, struggles inside her own head. Unable to move from her bed or play the piano she once was a master at, she pines for a freedom away from her debilitating illness and ultimately wants to release her husband of her burden.

The film’s climax is, well, typically devastating.

Amour is another recent film that garnered many Academy Award nominations – Best Picture, Best Director, Best Original Screenplay, and Best Actress in a Leading Role (Emmanuelle Riva was robbed here) – it still only managed to triumph in the Best Foreign Language Film category. That said, though, Haneke continues to prove why he is a revered filmmaker with Amour continuing a tradition of heart-wrenching, gut-punching, but beautiful cinema.

3. Rashomon (Akira Kurosawa, 1951)

Rashomon is widely considered to be the film that introduced Japanese cinema to Western audiences. To the surprise of many, it won the Golden Lion at the 1951 Venice Film Festival and then went onto win the Most Outstanding Foreign Language Film award at the 24th Academy Awards.

A short, concise tale about truth, honesty, and human nature, director Akira Kurosawa smartly riffs on the idea of the reliable narrator. The film opens under the Rashomon city gate as a priest (Minoru Chiaki) and a woodcutter (Takashi Shimura) retell the disturbing story of a rape, a murder, and its following tribunal. The film is then cleverly split into the different accounts of those involved: the bandit (Toshirô Mifune), the wife (Machiko Kyō), the deceased samurai (Masayuki Mori), and the woodcutter himself. Each account has stark and confusing differences but crucially each point towards an evil inherent in human nature.

Kurosawa’s bold and dynamic film style has cemented him in Japanese cinema history – and cinema history generally. Made famous by Rashomon and the following samurai films – notably Seven Samurai (1954) – Kurosawa was always a versatile and deft filmmaker.

2. All About My Mother (Pedro Almodovar, 1999)

Pedro Almodovar was first nominated in this category for his masterpiece, Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown (1988), that unfortunately lost out to Bille August’s Pelle the Conqueror (1988). Ten years later the Academy corrected that mistake and awarded Almodovar with his first ever Oscar for All About My Mother.

The film re-treads many Almodovar themes of motherhood and family, doing so here with a melodramatic but poignant piece of comedy filmmaking. Following the story of Manuela (Cecilia Roth) as she searches for the transgender father of her now deceased son, we are treated to colourful scenery, histrionic set pieces, and blossoming relationships. While in Barcelona, Manuela befriends local pregnant nun, Rosa (Penelope Cruz), and, along with her old friend Agrado (Antonia San Juan), guides her through single-motherhood. Again, Almodovar treats outsiders – prostitutes, transgender characters, and the mistreated – with a tender touch, showcasing his visionary and brave style that continually challenges audiences with sexual complexity.

A film about rekindling relationships and getting over past losses, All About My Mother seems an apt win for Almodovar who proved again that he was many steps ahead of the curve.

1. The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie (Luis Buñuel, 1972)

Luis Buñuel was a progenitor of avant-garde surrealism. Coming to prominence straight after his debut short film, Un Chien Andalou (1927), of which Roger Ebert once claimed to be the “most famous short film ever made,” Buñuel proved to many very quickly that cinema can push formal boundaries.

In The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie, though, Buñuel subdues his famous surreal compositional style – see his first feature, L’age d’Or (1930), for example – favouring situational comedy and absurdism. Like many of Buñuel’s work, he once again underpins the middle class society he lives in by drawing focus on its many flaws. He does so within the guise of a series of failed dinner parties held by six well-to-do sophisticates where unreliable hosts, military operations, adultery, drug dealing, and espionage interrupt the simplest of dinners in bizarre fashion. At first, what seems a series of humorous vignettes soon becomes complicated as each dinner becomes a Nolan-esque dream within a dream, ultimately making the characters seem even more ridiculous and more self-centred.

Buñuel was uninterested in Awards and when asked by the Academy to pose with his Oscar after winning Best Foreign Language Film – a ceremony he did not turn up to – he wore a white wig and large sunglasses. Even accepting awards, he found a way to combine absurdism with reality, truth with fiction. A true master.