Clearly there’s something special about Soviet cinema. At times, the Soviet Union found itself without a rival in its output, producing subversive and avant-garde fare that surpassed that of countries well-known for their quality filmmaking, including the U.S., France, and Japan.

And, of course, the wide range of Soviet movies contains many different forms of beauty that wow viewers to this day. From the poetic cinematic language of directors like Tarkovsky and Parajanov to the musical contributions to movies from such greats as Prokofiev and Shostakovich, there’s much to explore and enjoy. Here are ten of the most beautiful Soviet movies, each with their own unique contributions to world cinema.

1. Andrei Rublev (1966)

Director Andrei Tarkovsky’s Andrei Rublev is a meditation on the role of the artist, set amid the brutalities of Russia’s medieval period. This film captures the important role beautiful creative works play in imbuing meaning into people’s lives.

Andrei Rublev was Tarkovsky’s second feature film after his debut, Ivan’s Childhood. Turning to early 15th century Russia, Tarkovsky found the freedom to express himself in the sparsely documented life of Rublev, Russia’s most celebrated medieval icon painter.

Rublev spends his life wandering the Russian countryside, painting churches as he goes. Throughout his journeying, Rublev witnesses unbelievably cruel acts of violence. A grand prince has a jester’s tongue cut out for making jokes about him. Meanwhile, a nobleman has a group of stonemasons stabbed in the eyes so they won’t be able to repeat the beautiful craftsmanship that they had just completed on his estate. On top of that, the Tartars (a steppe people who then had dominion over Russia) raid the ancient city of Vladimir and murder countless townsfolk.

With this widespread suffering as a backdrop, we bear witness to Rublev’s stance on what the meaning of art is. In a debate with his mentor, Theophanes the Greek, Rublev reveals that he does not see man as inherently sinful, as all the violence that surrounds him might suggest. Instead, amid the many difficulties inherent in life, Rublev believes that art should serve to celebrate the beauty in the world and lift man up to embrace life.

The case in point of this the rejuvenating effect another artist’s work has on Rublev in the latter part of the film. After he kills a man during the Tartar raid of Vladimir, Rublev takes a vow of silence and withdraws from the world. Meanwhile, a teenage boy, Boriska, works night and day in leading an entire small town to make a beautiful, enormous church bell. As the gorgeous bell rings out, Rublev is seemingly healed. Witness to such beauty, he finds the inspiration he needs to continue with his life.

2. The Cranes Are Flying (1957)

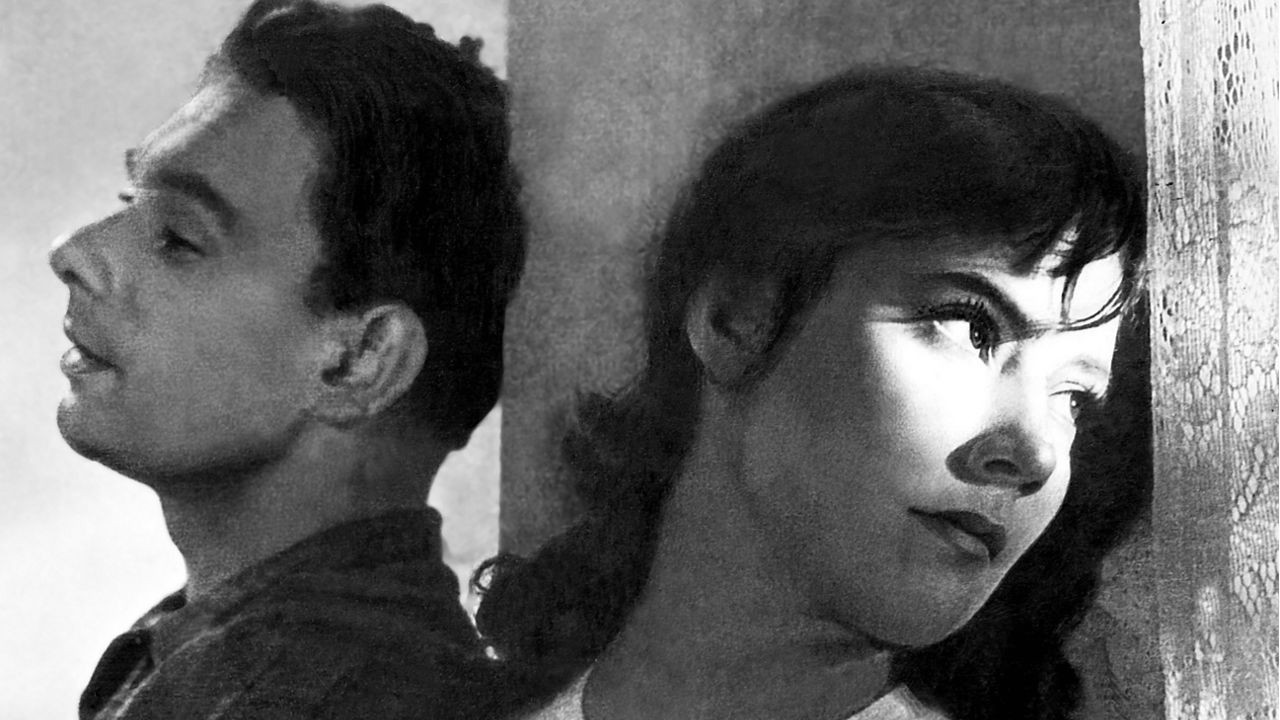

After the death of Stalin in 1953, The Socialist Realism movement that defined the cinema of the early Soviet Union started to loosen its grip on Soviet artists. In a step away from these previous conventions, The Cranes Are Flying was a groundbreaking film that focused not so much on glorification of collective sacrifice but instead praised the heroism in the complicated life experiences of individuals.

A film that takes place almost entirely on the home front during WWII, The Cranes Are Flying presented to Soviet and international audiences a novel lead character, sensitive and flawed. Veronika, our protagonist, starts the film prancing around beautiful pre-war Moscow with her lover, Boris. However, as soon as news of the German invasion comes in, Boris enlists and sets off for the front. In a heart wrenching and confusing scene, Veronika doesn’t even get to say goodbye, as she arrives too late to make it through the crowd of well-wishers.

Soon after, Veronika’s parents die in an air raid, and she is taken in by Boris’s family. Disaster continues to strike when Boris’s cousin, Mark, rapes Veronika during another air raid, and then Boris dies in a swamp (though she does not know it). According to the values of the time, Veronika is shamed by soldiers for her betrayal and met with countless silent looks of disapproval.

Nevertheless, Veronika goes on with her life, despite the humiliation she experiences. She works steadfastly as a nurse and never gives up hope that Boris is still alive.

Throughout this poignant movie, emotions run raw with the help of creative cinematography. As Boris collapses after he is shot, we are treated to an uncut, unedited camera swirl revealing the life he and Veronika could have shared were it not for his untimely death. As he falls to his knees, the camera spins in constant motion away from the birch trees above his head, up the staircase back home in Moscow to the apartment door from which the happy young couple pass in their wedding dress. Meanwhile, at the end of the movie, when Veronica finally comes to accept that Boris is gone, the frantic interplay between her – anxious, then heartbroken – and the joyful crowd around her makes it difficult to not grow tearful.

3. Hedgehog in the Fog (1975)

Sometimes labeled the greatest animation of all time, Hedgehog in the Fog is a beautiful work of art created by master animator, Yuri Norstein. In the 2003 Laputa Animation Festival in Japan, two Norstein works placed first and second in a poll of 140 artists and critics: Hedgehog in the Fog and Tale of Tales. Such accolades speak to Norstein’s special animation style and storytelling.

Norstein’s unique impressionistic animation style involves painting multiple glass plates and filming them on top of one another. By moving the glass plates side-to-side and towards or away the camera, he is able to create the effect of movement. You won’t find any CGI in any of his work. Rather, everything is done by hand. For example, he achieved the entrancing fog effect in Hedgehog in the Fog simply by moving a sheet of tracing paper away from the plates, towards the camera.

These amazing animation techniques really make you feel like you’re that hedgehog lost in the fog. In this poetic tale, the hedgehog is going to his friend, bear cub, as every night the two meet to drink tea with jam, and gaze at the stars. However, the hedgehog gets lost and soon encounters a series of terrifying experiences with various forest creatures. In the end, the hedgehog makes it to his friend and decides it’s better to be together than in the scary world outside.

4. The Color of Pomegranates (1969)

The Color of Pomegranates is a breathtakingly beautiful movie that explores the life of the 18th century Armenian troubadour, Sayat Nova. The film abounds in dazzling color, twinkling trinkets, and interesting traditions of the different peoples of the Caucasus.

A creation of Armenian director, Sergei Parajanov, The Color of Pomegranates expresses itself in a unique poetic language that is difficult to find outside of his works. Ostensibly, the film follows the life and times of Saya Nova. However, the plot almost doesn’t matter at all. Rather, gorgeous set pieces and alluring sounds transport you to how Sayat Nova must have experienced the world around him. You experience a similar, all-immersive world in other Parajanov films, from Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors, which draws you in to traditional Ukrainian-Carpathian culture, to Ashik Kerib, an ode to Georgian culture.

A common theme in Parajanov’s films is the celebration of a national identity in Soviet countries that was distinct from that of the Soviet Union. In The Color of Pomegranates, every traditional Armenian outfit, ornate object, and church scene is a celebration of Armenian identity – something that was being muffled during the Soviet period.

5. Hamlet (1964)

This Soviet adaptation of Hamlet was created by a constellation of some of the greatest artists there ever were.

Boris Pasternak (of Doctor Zhivago fame) provided the Russian translation of the original Shakespeare text. Notably, he transformed Shakespeare’s 17th century English into the colloquial Russian of the time, injecting into it an understandable, yet poetic voice that Russians rave about to this day.

Meanwhile, famed director, Grigori Kozintsev, masterfully created a convincing adaptation with stunning visuals. The Elsinore castle is set in the Ivangorod fortress on the border with Estonia. Ground level camera shots and frequent frames looking through the castle’s barred windows transform the building into a foreboding prison. On top of this, Kozintsev reconstructs Claudius into a Stalin-like character and condemns him for turning Denmark into a prison state. Such an interpretation of the Hamlet story imbues it with a political angle you won’t find in other adaptations. In this version, Ophelia is a victim of the malevolent Stalin-style-controlled state, and Hamlet himself is forced into his dilemma with this as a backdrop.

Of course, no mention of Kozintsev’s Hamlet (or other works) would be complete without praising the musical contributions of by Dmitri Shostakovich. The great composer and director worked together on film scores, all the way from New Babylon (1929) to King Lear (1971). In Hamlet, Shostakovich created a stirring score that majestically conveyed the emotional turmoil of the story.