The references to cinema of days past are never subtle when it comes to Quentin Tarantino’s filmography. From the very beginning of his career, he set out to pay tribute to and make art just like his heroes, ranging across all eras of the industry. However, there’s one specific era, the time in which his love for cinema was ignited as a child, that most of his passion stems from; the late 1960’s and early 1970’s.

It’s just that type of nostalgia that makes his latest film, Once Upon A Time… In Hollywood, so personal, and ergo, so reference filled. Set in 1969 on the advent of the shocking Manson Tate/La Bianca murders, the film follows Rick Dalton (Leonard DiCaprio), a once great T.V. Cowboy struggling to fit in with the ever evolving counterculture, and his best friend by way of stunt double Cliff Booth (Brad Pitt), the effortlessly cool war hero with intriguingly dark secrets. They fit into a world of real industry icons on both sides of the culture divide in this lovingly recreated swinging Hollywood, coming across the likes of Roman Polanski (Rafał Zawierucha), Charles Manson (Damon Herriman) and Sharon Tate (Margot Robbie).

Because of film industry setting, Tarantino carefully selected films from the era that his fictional characters could feasibly have starred in or seen, and uses them to build the world around them. Now, with the recently published novelisation of the film, a greater insight into the films that made Rick, Cliff and this world has been granted, adding to ones mentioned by Tarantino at the time of OUATIH’s release. Below are just a handful of the cinematic jigsaw puzzle pieces that made the film the 60’s cinema lover’s dream that it is.

1. The Born Losers (1967)

Eagle-eyed viewers will have noticed from the very first press shots of the film that Booth, Rick’s best friend and stunt double, wears a particularly interesting and appropriate denim jacket and black t-shirt combination. As stated in the novelisation, it’s the wardrobe for Billy Jack, the central character in Tom Laughlin’s 1967’s outlaw film The Born Losers. And just like the story states, if Cliff were a real stuntman at the time, there is no doubt he’d have worked on that film and kept the clothes.

Charming Vietnam war veteran Billy Jack (Laughlin), a half American half Indian, has taken to a life of loneliness and occasional vigilantism. However, when a deadly biker gang ride through a small California beach town, he sets into action to prevent them terrorising the locals.

Already, the central character is Cliff Booth all over. Laughlin plays the role without bravado, letting his charm simply be a by product as he rather violently and unapologetically gains justice. Scenes of him fighting the gang members so viscerally echo OUATIH moments in which Booth does the same to the Manson family, that what Tarantino writes in the novel feels very relevant; not only did the stuntman work on the film, but he remained good friends with Laughlin. A lot of the former’s personality comes through the film, and becomes an increasingly obvious inspiration for Booth and the type of films he would have conceivably worked on, creating deeper layers of understanding for the character through a real, cinematic language.

While Booth was inspired by many real stuntmen of the era, most notably using Burt Reynolds and his close friend and stunt double Hal Needham as a model for Rick and Cliff, both on and off screen, he seems far closer to Laughlin. With the similar Vietnam war veteran angle, he’s poised as somewhat of an onlooker to the film industry, not having fully devoted his career to it like the people surrounding him. Similarly, Laughlin would venture in and out of Hollywood, and just like Cliff, never really figured out his place within the changing tide of tinseltown.

2. Beyond The Valley Of The Dolls (1970)

Though released a year after OUATIH is set, and the fact there are plenty of other objectively better counterculture films from the era, this gonzo Russ Meyer directed trip is one of the absolute essential films in capturing the youth spirit of the late 60’s. From the free love to the insanely campy performances to the ritualistic drug use, Meyer and co-writer Roger Ebert worked to ‘damn the man’ in more ways than one, and crafted many party scenes and plot elements that Tarantino would use as a touchstone some 50 years later.

In an effort to secure a promised inheritance for their front-woman, hip rock group The Kelly Affair head to L.A.. Though they find instant success upon arrival, heartbreak, melodrama and even violence are just around the corner for Kelly (Dolly Read), Casey (Cynthia Meyers) and Petronella (Marcia McBroom).

Incredibly controversial at the time of release due to it’s sexual content, the party film has become a staple of cult classic cinema in the years since. It’s everything the youth at the time believed in; drugs, rock n roll, sex, and disillusionment with Hollywood, which is were the film dovetails well with OUATIH. Aside from the style, music and party scenes being a clear influence on the film (just compare it to the Playboy Mansion scene), Beyond is so heavily layered with biting satire of Hollywood that it demonstrates Cliff and Rick’s own struggles with the industry, albeit from a different perspective.

All of this culminates in what is possibly the most related scene, in which screenwriter Roger Ebert cheekily penned in a mass murder sequence that’s all too eerily similar to the Tate/La Bianca murders. At his Hollywood Hills home, famous record producer Z-Man Barzell (John LaZar) hosts a ritualistic drug fuelled night that results in him going on a murderous rampage and brutally killing some of the guests. It effectively tapped on the paranoia of the real murders of the time, adding to the mystic of the film. Tarantino uses this pulped up version of the event to his advantage for OUATIH’s final scene, similarly rewriting history, albeit in a much more violent fashion.

3. Gas-s-s-s! (1970)

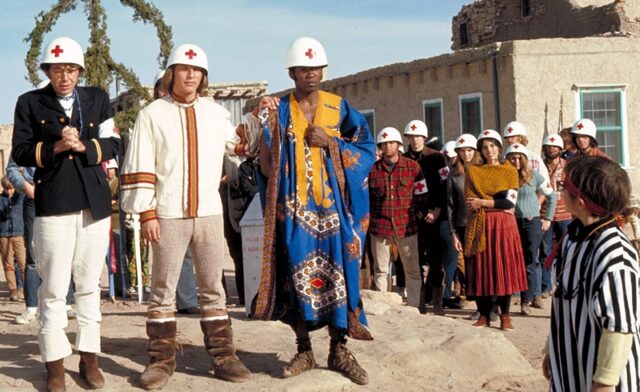

“Are you now or have you ever been a member of any organisation that advocates the violent overthrow of the government of the United States of America?”. “Yes… the Paul Revere & The Raiders Fan Club”. This kind of sharp political satire was oozing out of the counterculture at this time, especially through hippie cinema. This Roger Corman directed romp will be instantly recognisable to fans of OUATIH’s soundtrack with the use of a song from the film, but it has much more relevance to Tarantino’s latest than meets the ears.

After a deadly gas explodes across the globe, everyone over the age of 25 instantly dies, leaving the hippy youth to fend for themselves. Two teens in particular, Coel (Robert Corff) and Cilla (Elaine Giftos), navigate the desert in search of allies and supplies, and come across increasingly wackier scenarios. Expect car stealing cowboys, golf playing biker gangs and Edgar Allan Poe.

If there’s one film that audience’s can imagine Rick Dalton avoiding, it’s most definitely this one. It represents everything behind his now famous quote near the beginning of the film – “Fuckin’ hippie motherfuckers”. It’s send up of authority and willingness to let these ‘hippie motherfuckers’ take over is key in understanding Dalton’s distant for them, as it’s just further proof that his former T.V. cowboy fame is fading faster and faster in favour of this new, more youthful approach. The idea that these androgynous long hairs, the total opposite of his clean cut, macho ideal take control in the dream world of this film, is exactly what Dalton didn’t want.

The one scene that seals this is a shootout between Coel and the cowboys that he and Cilla meet in the desert, in which they accompany every shot at each other by shouting the name of a famous film or T.V. cowboy. Commenting on the blurred lines between the fantasied violence and the real, it’s all too appropriate to imagine Rick’s name thrown in among the rest.

The political satire Corman weaves through the film is so overt that it’s hard to believe there were any fans of the old Hollywood left at this point. With this being released a year after the Manson murders, and the Vietnam war raging even more, it’s a perfect snapshot of the culture war that Tarantino so dutifully recreates.

4. The Wrecking Crew (1968)

Though it can be argued that Sharon Tate doesn’t get enough screen time in OUATIH, especially compared to her fictional counterparts, the scene in which she cautiously enters a movie theatre to see her latest film on the big screen is pure cinematic joy. As Tarantino intended, it preserves the memory of her in a good light, as a rising ingenue as opposed to murder victim. Though the director has made his distaste for this film clear, and even going as far as to add in the film’s novelisation how much Cliff hates it too, it’s another key puzzle piece for this world.

The fourth in the Matt Helm series of comedy spy films, the titular hero played by ‘king of cool’ Dean Martin is sent on a mission to prevent an evil count (Nigel Green) from destabilising global financial stability. Along the way he teams up with Frey Carlson (Sharon Tate), and the duo travel across the globe before battling the mastermind and his accomplices, Wen Yu Rang (Nancy Kwan) and Linka (Elke Sommer).

Not much more than the lighthearted, pulpy James Bond rip off it was intended to be, this product of spy-mania was even a relic by the time of it’s release in 1968. Being lead by an actor cut from the same cloth as Old Hollywood staples such as Rick Dalton, it’s attempts to be hip this late into the counterculture movement fall woefully flat. However, in that, it makes for a great companion piece to OUATIH in demonstrating how Hollywood was shifting at the time.

Tarantino even goes as far as to show Sharon having flashbacks to her fond memories of stunt training for the film with none other than Bruce Lee, who of course made a memorable and now controversial appearance in the film. Keeping these moments, in which Robbie portrays Sharon as opposed to stock footage from The Wrecking Crew that she is seen watching, short and sweet helps in using this film as a great jumping off point for understanding her as a character within Tarantino’s fictionalised world. Mixing Robbie’s Tate in with the real, albeit briefly, so effectively places his film in reality that it’s impossible not be engrossed.

5. Gunman’s Walk (1958)

In one of the many inspirations that formed DiCaprio’s Rick Dalton, Tab Hunter in this film, as the dashing yet conflicted cowboy Ed Hackett, can arguably be considered chief among them. Displaying serious acting chops in what is really quite a brilliant screenplay for a western of this era, the connections between Hunter’s misunderstood anti hero are all too clear to connect with Dalton in his fictitious show Bounty Law, and later roles in Spaghetti Westerns.

The two sons of Lee Hackett (Van Heflin), Davy (James Darren) and Ed (Tab Hunter), land in a Shakespearian feud as the half French/half Sioux love interest Cecily (Kathryn Grant) comes between them. After a fierce competition between Ed and Cecily’s brother Paul (Bert Convy), Ed is under fire as his riding results in the death of one of Paul’s fellow Indians, and Ed’s prejudice, family and loyalty all come into question.

Just as with OUATIH’s Rick, the late 50’s were Hunter’s golden era. Known as a clean-cut cowboy, he was somewhat of a Hollywood heartthrob who didn’t mind being typecast. After all, with both actors, it was how they made their fame. However, as OUATIH makes it clear, that high doesn’t last forever, with Dalton following in Hunter’s footsteps and relocating to Europe to star in Italian westerns by the end of the 60’s in a risky move to reignite their careers. What makes Gunman’s Walk so special, and more in line with Tarantino’s latest, is it’s surprising subversion of the western genre and how it echoes similar cultural tensions to ones that would be depicted in the film.

Most of our time with Dalton is spent seeing him come to terms with playing ‘the heavy’ on Western T.V. show pilot Lancer, in what is implied to be part of a string of similar roles as his heroic star fades. Though Hunter’s Ed Hackett is the lead of Gunman’s Walk and still a heartthrob, his evil actions here essentially make him ‘the heavy’ of the film, and put his star status at the time in an interesting context. Additionally, the distain he holds for the native Indian’s echo similar racial tensions that would occur through the majority of the next decade, and hint at Dalton’s prejudices in the culture war between he and the hippies of 1969.