Montage Theory, the staple of college Cinema Studies classes, holds that the juxtaposition of images via editing can make meaning beyond what can be represented visually. Described by Soviet filmmakers in the 1920s, who sought to apply their new country’s philosophy (dialecticism) to this exciting new art form of cinema, montage theory has since found its way to Hollywood and beyond. Many filmmakers have put their own spin on the montage to marvelous effect. This list will explore which films demonstrate the potential of montage and its effect on cinema history.

1. The Smiling Madame Beudet (1923)

An early feminist filmmaker, Germaine Dulac also wrote film theory and once argued that meaning happened both within and between the shots. Though aligning more with Impressionism and Surrealism, her films use editing to establish a character’s interiority.

A great example of Dulac’s “proto-montage” can be found in The Smiling Madame Beudeut, a forty-minute portrait of the eponymous character in an oppressive marriage, as various shots illustrate her thoughts and feelings. Her husband asks if she wants to attend an opera and the viewer sees Madame Beudet’s imagination of men in ridiculous costumes surrounding a woman and singing at her. Even this comic inset illustrates an oppressive patriarchy. Dulac continues this use of editing. Within the confines of the home, close up shots of things like clocks and flowers become more than details, but instead deeper signifiers of the heroine’s struggles. Though not a true example of montage, Dulac’s work in Madame Beudet shows the evolution of editing in narrative film and how it can be used for artistic, philosophical effect.

2. Battleship Potemkin (1926)

The main proponent of montage theory, Sergei Eisenstein, practiced what he preached in his own films. His October: Ten Days That Shook the World (1928) beautifully explores what he calls “intellectual montage” (editing designed to make the viewer think, rather than feel). This montage shows shots of different deity statues from different cultures, questioning the idea of “God,” in the phrase “For God and country.” However, the “emotional montage” in Battleship Potemkin, in which soldiers massacre unarmed civilians as they protest on the Odessa steps, lives on film history for its affective horror.

Intercut shots of people fleeing, shrieking, dying, and mourning collapse time and space in a moment of shared suffering despite very little on-screen violence. For example, at one point the soldiers shoot a woman in the eye. The impact never appears on screen, but the before and after shots, as the woman screams while blood streams down her face behind her broken glasses, edited with shots of other horror, sears in the viewer’s mind. The Odessa Steps scene, and the famous moment when a baby in a carriage hurtles down the steps away from the dead mother, has spawned many homages including Brian de Palma’s The Untouchables (1987).

3. Man with a Movie Camera (1929)

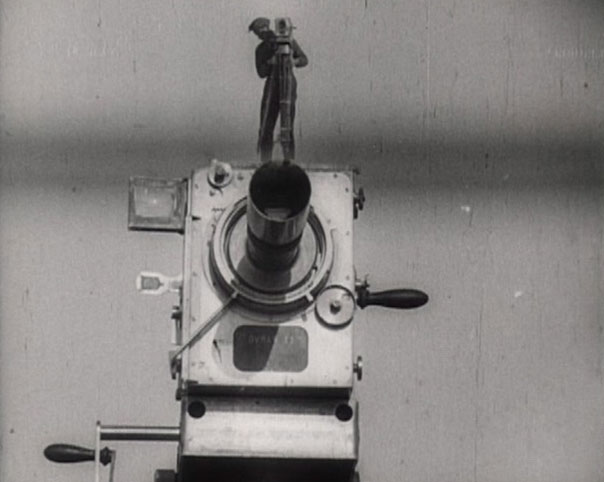

Directed and edited by husband-and-wife team Dziga Vertov and Elizaveta Svilova, Man with a Movie Camera creates a mesmerizing portrait of a Soviet city and its inhabitants without any plot through montage editing. Towards the beginning of the film, a woman awakens and washes her face. She opens her eyes, then the film cuts to window shutters opening, then to the camera itself as the lens focuses in on flowers.

Other juxtapositions are darkly comedic. For example, in one scene a newly married couple joyfully signs papers at a courthouse. The next shot shows a different couple signing divorce papers at the same place. Nearly a century later, Man with a Movie Camera remains one of the most innovative films when it comes to editing and how it creates meaning.

4. Psycho (1960)

Like the Odessa Steps sequence in Battleship Potemkin, the shower scene in Psycho is famous for its violence despite showing very little, through the power of montage. The scene begins as the heroine Marion Crane (Janet Leigh) enjoys a shower in her shower room, until a masked intruder enters and draws back the current revealing a raised knife. Coupled with an unforgettable soundtrack of sharp, screeching violin music, the rapid intercuts shots of a gleaming, thrusting knife and Leigh’s horrified face and exposed skin simulate the violence of the stabbing.

Hitchcock retains the power of the quick montage by following it with a long take of Marion’s dead eyes, then her blood slowly swirling down the blood, forcing viewers to absorb what they’ve seen and cementing Psycho as a classic horror film.

5. The Godfather (1972)

Almost as famous as the aforementioned Odessa Steps sequence or the shower scene from Psycho, the baptism scene from Francis Ford Coppola’s The Godfather remains a staple of film school and montage theory. In this scene, anti-hero Michael Corleone attends his niece’s baptism and solemnly renounces Satan to become her godfather. At the same time, his subordinates carry out multiple murders on his command.

The editing goes beyond cross-cutting, though the action does take place simultaneously. However, the juxtaposition draws a connection between religion and the mob, both integral parts of Michael’s identity, family, and culture. The true ritual, though, is not the baby’s baptism, but Michael’s, as he accepts his role in the mafia. Once again, this montage style of editing creates a deeper meaning to both scenes (the baptism and the murders) than either would have alone.