5. Muerte de un ciclista/Death of a Cyclist (1955, Juan Antonio Bardem)

Juan Antonio Bardem, a staunch Communist and a strong advocate for more experimentation, social criticism, and intellectual substance in Spanish cinema, expresses his beliefs and criticisms of Franco’s regime wholeheartedly in this social realist drama that simultaneously resembles a murder mystery and a classic noir.

Within the first few minutes of the Death of a Cyclist, the title is played-out in full: Juan, a mathematics professor, and María José, a wealthy socialite, hit a cyclist on their return from an adulterous engagement. After briefly contemplating their next move, they leave the victim on the side of the road to die in order to ensure their relationship’s secrecy. The rest of the film reveals the psychological effects of their actions and how their fear and guilt grow into uncontrollable paranoia.

Although the film begins with a forbidden romance, Death of a Cyclist is not a story of a love triangle. It is an exploration of a triangle of distrust between Juan, María José, and Rafa, an art critic and guest to Juan’s parties. Spurred on by the misunderstanding that Rafa may have witnessed the illicit couple’s actions on the road, Juan and María José’s anxiety grows; however, it manifests itself differently in the two – revitalizing Juan’s moral and social awareness while furthering María José’s detachment from society.

Bardem masterfully presents the exchanges between the three with irony, suspense, satire, drama, and suspicion. This combined with Bardem’s most noticeable stylistic feature, namely his exceptional – although sometimes disorienting – use of jump cuts and dissolves, effectively juxtapose the social environments of the bourgeois and working class. By doing so, he critiques a Spanish society in which the rich are above the law and the bourgeois only seek secrets in order to exploit the rich.

Death of a Cyclist offers endless layers to analyze, and the film continuously proves to be an evocative depiction of the interplay between knowledge and power and between justice and injustice. If the film needs any more draws, cinephiles will be especially intrigued to learn that Italian actress Lucia Bosè, who plays María José, was dubbed for the original Spanish release of the film and that director Juan Antonio Bardem is the uncle of internationally renowned actor Javier Bardem.

4. El Verdugo/The Executioner (1963, Luis García Berlanga)

Arguably one of the most influential and prolific filmmakers during Francoist Spain, Luis García Berlanga earns two spots on this list, The Executioner being his first, and one in the honorable mentions. Along with Juan Antonio Bardem, Berlanga is considered one of the pioneers of post-war New Spanish Cinema, and his films often achieve legacy-status as masterpieces of Spanish history.

In collaboration with his long-time screenwriting partner Rafael Azcona, Berlanga was able to dodge Franco’s censorship and create this black comedy that follows the story of Amadeo, a retiring executioner who gets José Luis, a funeral employee, to marry his daughter and take on his job in order for him to keep a state-subsidized apartment. Like many of Berlanga’s films, The Executioner relies on one main joke but reaches its punch-line through a humorous tale full of irony and brilliantly overlapping dialogue presented by a lively ensemble cast.

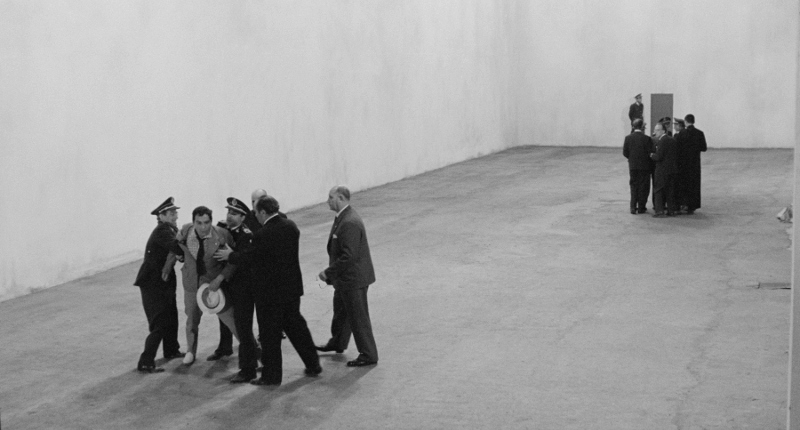

The punch-line in this case is that José Luis takes on the role of executioner with the promise that he will not have to complete any executions, but the final scene shows him being unwillingly dragged off to the garrote to complete his duty. The end is partially based on the true story of José Monero, an executioner during Franco’s reign who did not want to carry out his job. He ultimately executed only one person, Heinz Chez, during his tenure and then left the office vacant.

Berlanga succeeds in hitting the punch-line with great force, but it’s the serious nature of the subject and the somber delivery that make it all the more effective. At its close, The Executioner is a critique of capital punishment as well as the social values of Francoist Spain and the ethical traps society can easily force upon us.

3. El espíritu de la colmena/The Spirit of the Beehive (1973, Víctor Erice)

The Spirit of the Beehive, Víctor Erice’s debut film and one of only three feature works in his whole career, is nothing short of a masterpiece and will leave you asking what else the director could have produced. Set in 1940, just after Franco’s army defeated the Republicans in the Spanish Civil War, the film follows Ana, a young girl who becomes obsessed with James Whale’s 1931 Frankenstein when a traveling theater brings it to her small town.

Although released in the later years of Franco’s regime, the film still experienced restraints and censorship; however, this turned into a benefit by forcing Erice to present his social critiques with subtlety and artful symbolism. A film critic or historian of Spain during this time could spend hours discussing and debating the meaning behind such symbolism, but even a casual viewer can understand the poetic nature of Erice’s work.

Republican oppression under Franco forced many citizens to live in silence, highlighted by the minimal dialogue and bleak landscapes in the film. Within this silence, however, the Spanish people could use secrecy as a weapon to resist the regime. It is this secrecy – and its power to isolate individuals and separate families and societies – that Erice explores as Ana’s fantasies of her fictional monster lead her into trouble as she aids a wounded Republican soldier hiding in a nearby barn.

Resembling both the poetic and visually stunning nature of works by Abbas Kiarostami and Andrei Tarkovsky, there is no question why this beautiful piece of meta-cinema has gone on to inspire filmmakers like Guillermo del Toro, who has multiple movies exploring similar themes, like the imagination of children during the Spanish Civil War and post-war era.

2. Viridiana (1961, Luis Buñuel)

Anyone familiar with the history of cinema will instantly recognize Luis Buñuel for his famous surrealist short film, Un chien andalou, made in collaboration with Salvador Dalí. Buñuel’s legacy continued for decades after his introduction into the silent era, and he worked across multiple genres and countries, including Spain, Mexico, and France.

Franco’s rise in Spain was the catalyst for Buñuel to flee the country and become a Mexican citizen, and it was not until the making of Viridiana that he returned from his 29 year exile with the help of Juan Antonio Bardem’s production company, UNINCI. The true reason for Buñuel’s return is unknown – but so is the nature of the master surrealist – and his film was short-lived in Spain, only being allowed to return to the country after Franco’s death.

Buñuel is undeniably a true original, and Viridiana showcases his brilliance and his instantly recognizable, unapologetic style. Partially based on Benito Pérez Galdós’s 1895 novel Halma, the religious satire focuses on Viridiana, a young novice who is about to take her vows and enter a secluded life in the convent until her Mother Superior encourages her to visit her dying uncle Don Jaime. Viridiana visits out of charity, however, when she arrives, Don Jaime realizes she perfectly resembles his late wife, and then Buñuel’s classic sarcasm, dark humor, and sardonicism take hold and unfold into a scandalous tale.

As the king of satire, Buñuel does not shy away from suggestive or anti-clerical depictions; however, he refrains from taking any direct stance. His premeditated shots come across tastefully, and his twisted plot revels in bitter humor, leaving the viewer with a film that is unmistakably Buñuelesque.

If you are already a fan of Viridiana, check out another Buñuel masterpiece, The Exterminating Angel, in the honorable mentions.

1. ¡Bienvenido, Mister Marshall!/Welcome Mr. Marshall! (1953, Luis García Berlanga)

Welcome Mr. Marshall! is the earliest film on this list and the second movie listed by esteemed writer-director Luis García Berlanga. Originally commissioned by the state to make flamenco singer Lolita Sevilla a comedy star, Berlanga collaborated with fellow pioneer of New Spanish Cinema, Juan Antonio Bardem, but the two decided to give the film more meaning than their original mandate. The result is a masterful satire and arguably the first great Spanish film of this new era.

With the title being a direct reference to the Marshall Plan, Welcome Mr. Marshall! details the story of a small, poverty-stricken Castilian village that plays into typical Spanish stereotypes in order to garner money from the American post-war aid program. The townsfolk hire a famous flamenco singer, dress in traditional Andalusian-style clothing, and redecorate the town as they think this will make their village more appealing to the visiting Americans.

Two notable techniques stand-out in the film: Berlanga’s use of narration and his inclusion of a dream sequence. While narration is nothing original by itself, Berlanga’s first scene reveals that his use of it will be unique. He opens the film with the narrator describing the town and subsequently pausing the film and removing all of the people from the screen, only to introduce them one-by-one later on. In regards to the dream sequence, Berlanga utilizes it to showcase the other end of the stereotypes, those of what the Spanish view as American culture. Most interestingly, the deaf mayor dreams he is a wild west cowboy and speaks in indecipherable dialogue.

Although Welcome Mr. Marshall! is the first feature film solely directed by Berlanga, his style is evident with his overlapping dialogue, comedic satire, and strong ensemble cast. The film also ends on his classic one-joke punchline – on the day of the American’s arrival, they drive through the town without even stopping, reflecting Spain’s actual exclusion from the Marshall Plan. The film is truly a criticism of the stereotypes between the two cultures and what Spain was simplified to during Franco’s reign.

Anyone of Berlanga’s films could easily make this list, but it is his first that deserves this spot and maintains the most international recognition to this day. It is a must-see for anyone looking into the history of Spanish cinema.

Honorable Mentions: Plácido (1961, Luis García Berlanga), Surcos/Furrows (1951, Jose Antonio Nieves Conde), Furtivos/Poachers (1975, José Luis Borau), Peppermint Frappé (1967, Carlos Saura), El ángel exterminador/The Exterminating Angel (1962, Luis Buñuel)