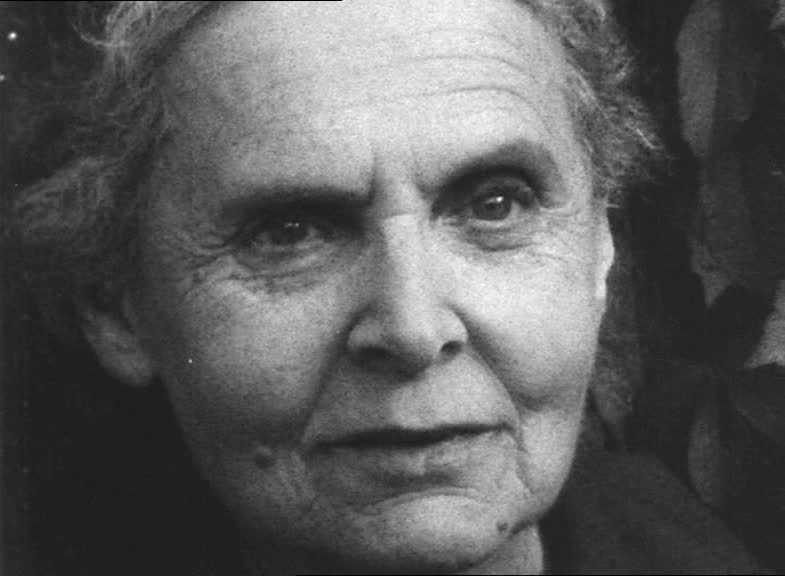

6. Elsa La Rose (1966)

Elsa La Rose is a short, avant-garde documentary, where Varda captures the relationship between writer Elsa Triolet and surrealist poet Louis Aragon.

As you would expect about a film featuring the romantic relationship of two writers, Louis Aragon recounts the beginnings of their relationship in gorgeous, sensitive and poetic language. While, Elsa speaks honestly and bluntly about Louis. The couple describes meeting for the first time whilst recreations of their first meeting play over the screen.

Varda’s intelligence as a filmmaker is on full display here, as by having both Louis and Elsa describe the same event, we see their differing approaches to life. Louis often includes superfluous but beautifully observed details in his recounting first meeting Elsa whilst Elsa is direct and to the point, describing things with clinical detail. With one simple scene, Varda manages to communicate to her audience the major differences in personality between her subjects – their chosen style of communication – and what helps to make them unique individuals – their worldview.

Additionally, Louis notes that his poetry was greatly inspired by Elsa, he remembers having ‘lost his way as an artist.’ As such, Elsa La Rose is a film that unpacks the contrast of being both an artistic muse and in a loving relationship. Yet, Varda’s film never confuses the two, never once mistaking being a muse for being in a committed, loving relationship.

Crucially, an interview with Elsa notes that the poems themselves do not make her feel loved but, in fact, life itself is what makes her feel loved – spending everyday with her partner makes her feel loved. This perhaps is the films greatest strength, in that it manages to look both at the couples artistic, creative relationship and their personal, loving relationship, without ever confusing the two. Elsa La Rose is a short, effective and honest piece of work.

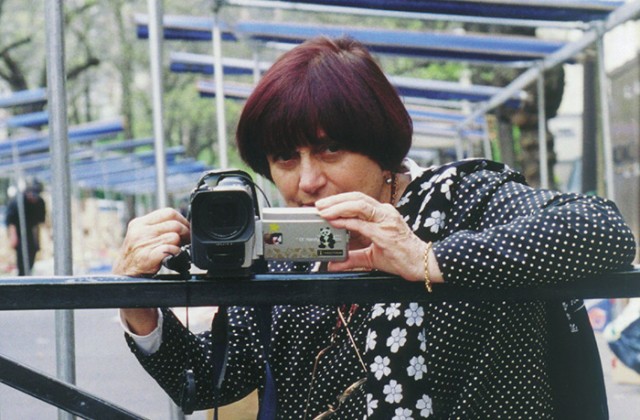

7. The Beaches of Agnes (2008)

The Beaches of Agnes is an autobiographical documentary where Agnes Varda guides the audience through her life and personal experiences.

In her work, Agnes Varda has always been a rule breaker – whether it’s adhering strictly to real time constraints in Cleo From 5 to 7 or use of non-linear techniques in Vagabond – and Beaches is no different. Varda continually shows the audience things they aren’t meant to see. For example, in Beaches she regularly includes shots of her crew setting up, taking the audience out of the story and reminding them they are watching a constructed piece of work.

Additionally, Varda allows for parts of the film that do not necessarily work to remain in the finished piece. Notably, in search of herself, she revisits her childhood home in attempt to reveal something deeper. Varda drolly comments no ‘grand revelations’ occur. In most films, this sequence would be seen as an experiment that failed and left on the cutting room floor. However, Varda leaves it in. Ultimately, by allowing these moments that didn’t work as she would have hoped to remain in her film, Varda creates a greater sense of intimacy with her audience, through her honesty. The audience feel like Varda isn’t hiding anything from them and is willing to share everything about this experience, both the highs and the lows.

This sense of intimacy continues throughout the film. Specifically, where Varda recreates sequences from her childhood but admits she doesn’t know why. Interestingly, Varda comments that ‘memories are like flies swarming through the air,’ they are ‘bits of memory, jumbled up.’ This seems to be Varda preoccupation with the titular beaches, to go through the memories of her life and try to make some greater sense of them, to figure out what matters to her and why. Whether she succeeds or not, is kind of up to her, but it is always engrossing to watch her try.

As a result, it’s hard not see Varda as someone who views film as a way of preserving memory. Film allows the directors thoughts, feeling and ideas to live on long after they pass. Varda celebrates her 80th birthday on camera in one sequence and mourns the death of her husband Jacques Demy in another. Through looking at memory and aging, Beaches is clearly a film where Varda is recognising her own her mortality. Perhaps, this is why she is so transparent with her audience. Either way, this unique mood that Beaches possess makes for an emotional but delightful watch.

8. Jane B Par Agnes V (1988)

Jane B Par Agnes V is arguably the most distinctive film on this list. The film regularly blurs between fiction and non-fiction. Here, Varda interviews English-French model, singer, actress Jane Birkin about her acting career and her life in general. The pair decide what roles they would like to see her splay, then the audience sees Jane act in these roles in short fiction pieces.

As a subject, Jane grants Varda unprecedented access to her creative process and Agnes Varda, herself, seems to be clearly having fun playing with documentary conventions. The film opens with a long take. Jane recounts being alone on her 30th birthday in a monologue direct to camera. The continuation of the take is a bold and impressive way for Varda to open the documentary. Furthermore, Varda’s refusal to cut to anything else, demands the audience’s attention and communicates that Jane is a woman with stories, a woman to be heard.

These stories are revealed in fits and starts across the documentary. Jane is an incredibly sympathetic subject and the film seems to have a paradox at its core. Many collaborators, see Jane a muse, someone who inspires something deep from within them. However, the film notes that muses can often get left behind when artists move on. As the muse, Jane confesses she doesn’t always know what she is to do when this happens. Yet, Varda herself could be seen as using Jane as muse only for her, also, to leave her behind.

Clearly, the film is not an easy watch. It is at points knotty, complicated and absurd. Even Varda herself notes she intended for the film to wander, remarking – ‘I like mazes’. Though, if the audience can look past this fact and focus on the moments of real honesty from Jane, they’ll find plenty to enjoy here.

9. The Gleaners and I (2000)

Traditionally, Gleaning, is the act of collecting the leftover grain after the harvest. Conversely, in her film, The Gleaners and I, Varda looks at gleaning both literally and metaphorically. On a literal level, she meets though who collect grain after the harvest. On a metaphorical level, she meet those who salvage. For example, Varda visits a man, who has a job, but has lived off of salvaged items and food for nearly ten years.

This sequence seems to be the heart of the documentary. Varda uses gleaning as a topic to look at all things forgotten and left behind – whether it be old food, clothes or even people. One of the film’s most tragic scenes sees Varda interview a man living in caravan. Having gone through a divorce, the man has no money – he goes through bins to feed himself, he has lost his wife, children and cannot even afford to go and visit them. He belongs very much to a community of forgotten people.

Most poignantly, Varda even comes to the conclusion that she, herself, is a gleaner. Her films pick up topics others wouldn’t touch – as if they were off the floor – and make human and moving narratives out of them. This is level of empathy is ultimately what makes The Gleaners and I such a powerful film. It really is astonishing and a testament to Varda’s filmmaking prowess that a film that seemingly begins about those who collect grain can turn into such affecting viewing.

As time passes, the films relevance only seems to grow. Especially considering it now – in an age where recycling and caring for the planet is becoming increasingly more pivotal than ever. The Gleaners and I is Varda at her truly empathetic best.

10. Faces Places (Co-Directed with JR, 2017)

Faces Places follows Varda and artist JR – a man who religiously sports black sunglasses and a fedora – travelling around rural France. The pair create murals and artwork out of the faces of the people they meet.

During their trip, Varda and JR uses neat filmic techniques to help create a sense of intimacy within the work. Specifically, when discussing ideas and influences for their murals. JR and Varda film themselves in a wide shot with their backs to camera. This helps instil a feeling in the audience that they are eavesdropping on a private conversation between both two artists but, also, two close friends.

Importantly, this friendship helps to provide the documentary with profound access into personal aspects of Varda’s life – like her on-going battle with her deteriorating eye sight. Had she not made the film with JR, Varda may not have been willing to reveal this or presented herself in such unflinching detail. Yet, the audience being privy to this knowledge helps to adds greater depth to the filmmakers’ journey. If a filmmaker of Varda’s prowess is suffering with an eye disease, it becomes evident this might be her last chance to capture and compose cinematic images exactly as she wants them.

Moreover, Varda and JR’s friendship what makes viewing Faces Places such a heart-warming experience . Despite being 55 years apart in age, this friendship between the directors – Varda and JR – feels very real and very powerful. They tease each other, laugh together and support each other. The strength of the friendship is represented in the films climax – where the pair head to Jean Luc Godard’s house, only for events to take a turn for the worse. As Varda’s eyes begin to tear, JR puts a kind reassuring arm around her in a truly powerful scene.

Appropriately, Faces Places scored Varda her first and only Oscar nomination. At 89, Varda became the oldest Academy Award nominee for any non-honorary Oscar. Even if it was many years too late, it is a fitting end to a brilliant career that the Academy finally recognised Varda and her immense talent.