Quinqui, pronounced “kinky,” coming from the word “delinquent,” is a Spanish film genre that explores working class life during the Transition period. For those who may not know, the Transition is from 1975, the fall of the fascist dictatorship to democracy in the late 1980’s. While politicians grappled for a dignified, moderate identity in the midst of Franco’s death, the disgruntled youth swung in the opposite direction. In a storm of graphic violence, casual sex, homoeroticism, AIDS, police brutality, and drug use, specifically heroin use, which ran rampant in Spain throughout the 70’s and 80’s, Cine Quinqui portrays a raw portrait of Spanish society in a time of crisis.

Free for the first time in forty years, Spanish directors no longer faced censorship and could create the chaotic, joyful, taboo cinema people had craved for so long. Enamoured with freedom and hedonism, Quinqui filmmakers captured the complex, romantic nature of the teenage delinquents who broke the mold of what could and couldn’t be done in a post-Franco society.

Seeing as this wasn’t a hot topic in the academies, directors often found their actors in the street. They were often delinquents themselves, and went on to work with Quinqui directors to portray their lifestyles, like Jose Luis Manzano and El Torete. Unfortunately, many died quite young from heroin overdoses or AIDS.

Despite its raw, B-film quality and low-brow content, Cine Quinqui has been integrated into the Spanish canon. In the same way that the French New Wave is emblematic of France in a time of flux, or Italian Neo-realism is emblematic of an Italy in crisis, Cine Quinqui reflects Spain’s slow, seemingly endless climb out of a fascist dictatorship.

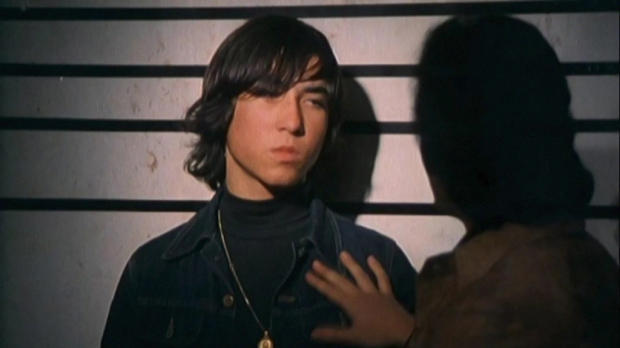

1. Knifers (1980)

Director Eloy de la Iglesia sets the tone of Quinqui philosophy by opening Knifers (Navajeros in Spanish) with Ten-Si’s quote: “Men don’t become criminals because they want to, but have been driven towards crime out of misery and necessity.” Based on the life of José Joaquín Sánchez Frutos, aka El Jaro, a teenage delinquent who, like many Quinqui protagonists on this list, started his life of crime at a very young age.

The child of negligent parents who locked them in a room to go out drinking and spend the money their children earned when they escaped to go out begging, El Jaro had to put his childhood on hold to survive. However, De la Iglesia doesn’t criticize the parents directly in Knifers, but uses the foil between his mother, a sex worker, and Mercedes, his lover who shares the same age and occupation as his mother to express how the adults are simply pawns in a bigger, more evil mechanism— fascism.

Only five years after Franco’s death, many families were in dire straits, criminalized, leaving parents and even children to turn to escapism, like heroin and alcohol. This is a recurring theme in Knifers— the constant need to escape, whether from a building crowded with cops or an uncomfortable feeling. Yet even in destroying architectures of entrapment, like the gang of boys who pour through the doors of a drug dealer’s house to save El Jaro, De la Iglesia takes a cynical tone for Spain’s lost generation of the Transition. By juxtaposing his death, a gunshot wound to the head with the birth of his child, De la Iglesia seems to suggest that the cycle is bound to continue.

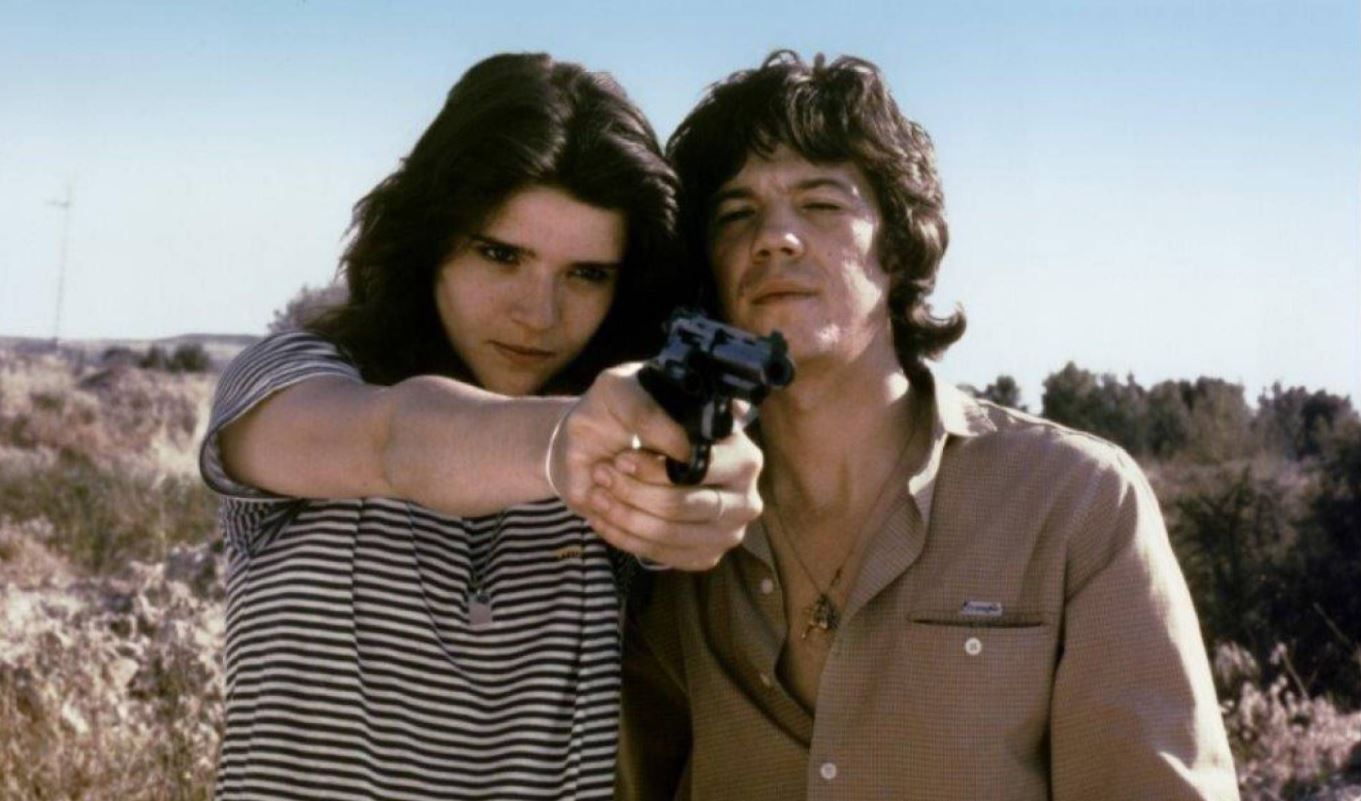

2. Street Fighters (1977)

One of the most emblematic films of Cine Quinqui, Street Fighters (Perros Callejeros in Spanish) depicts the lives of three Romani teenagers who set out for a life of grand theft auto, petty crime, and the good life. Similar to A Clockwork Orange in its attitude, structure, and most of all, its bizarre turn of events, Street Fighters completely disregards narrative norms, reflexively behaving like its boundless protagonists.

Not so much interested in plot so much as a theme, director Jose Antonio de la Loma encapsulates the burning desire for freedom and the desperation to maintain it, specifically with his protagonist, El Torete, who manages to slip out of anything, even prison and shootouts. However, while it’s easy to write off Street Fighters as an action film with some saucy one-liners, De la Loma, like De la Iglesia, frames his story with an empathetic lens.

While he suggests that the protagonists are criminals as a means of survival, he also suggests that the police aren’t concerned with protecting and serving the public so much as they enjoy abusing their power on people who can’t question them. De la Loma conveys this in one scene in particular, where a woman is supposed to identify the boys who assaulted her, only to remain silent when she sees how the police hit and insult them.

In the dawn of a new chapter in Spanish history, De la Loma questions the role of authority figures, but, as represented in his signature abrupt endings, he doesn’t seem to have an answer.

3. What Have I Done to Deserve This?! (1984)

Pedro Almodovar isn’t what many consider to be Quinqui, but rather a pillar of the Movida Madrileña, a more hedonistic, flamboyant Spanish film genre that occured around the same time. However, in his adaptation of Roald Dahl’s Lamb to the Slaughter, Almodovar dips into the Quinqui genre with his slew of absolutely unhinged characters. From her teenage sons who dream of sex work and drug peddling, a father-son forgery duo, and a pill-popping housewife finally cracks after her husband shamelessly courts an old flame, a famous German singer and nazi sympathizer, Almodovar calls on the same yearning for escape and freedom typical in Cine Quinqui.

Shot in a rougher, grayer style than Almodovar’s crystal clear, romantic, and colorful norm, What Have I Done to Deserve This?! works on the viewer’s anxiety on an aesthetic level as well. By keeping audiences trapped inside the crowded, dim spaces with Gloria, the protagonist, Almodovar inspires empathy with the delinquent.

What Have I Done to Deserve This?! was a box office hit, both domestically and internationally, and shot Almodovar to A-list status.

4. Overdose (1983)

In Overdose (El Pico in Spanish), set in Bilbao, where the rain never seems to give way, a sort of star-crossed friendship grows between two boys, Paco and Urko, one whose father is the chief of police and the other a communist politician. The bond that glues them together? Heroin. Yet as the boys fall deeper in the ever-deepening hole that is addiction, they turn to a life of crime together.

Full of twists, turns, and false endings de la Iglesia makes an interesting metaphor by comparing the addict’s cycles of abuse to the uncertainty Spain faced as a nation in the twilight of the transition. Ten years after the initial fall of the Francoist regime, the conflict between fascist politicians and communist radicals had yet to stabilize, leaving many in a state of uncertainty and a desire to escape the pain. As demonstrated with the juxtaposition between Paco and his mother, who is terminally ill throughout the film and uses similar drugs as her son to subdue her pain, De la Iglesia depicts the many colors of escapism during the Transition. “It brings me peace,” both mother and son say.

With his motifs of water, Overdose expresses not only the desperate search for instability in a flood of vastness, but also the release of repressed emotions buried during Franco’s regime. From vast, ocean backdrops to cathartic walks alone in the rain, De la Iglesia throws even his most staunch characters, police men and strict fathers alike, into profound introspection and re-evaluation.

5. Hurry, Hurry (1981)

Before anything else, Hurry, Hurry (Deprisa, Deprisa in Spanish) has an amazing soundtrack. Composed of various Flamenco groups, like Los Chunguitos and Loli y Manuel, director Carlos Saura uses the raw emotions of Flamenco to pull at his viewers’ heartstrings, but also develop the characters through music at key points of the film, like when Angela and Pablo fall in love at first sight or when the gang of kids peel out in their getaway car.

Empathetic towards his characters, where the general public saw them as delinquents, Saura shows the gang in arcades, in restaurants drinking milk, peppering various oral fixations to suggest that despite their criminal activities, Saura suggests that the kids are just that— kids. However, the police are not as sympathetic to a stunted generation that never had the privileges to simply be children, and when the gang flies too close to the sun in their most ambitious and deadly heist, they perish, preferring death over prison.

Hurry, Hurry made big waves not just in Spain, but in all of Western Europe, winning the Golden Bear in Berlin in 1981.