5. Mrs. Miniver (1942)

There aren’t many films that can earn the plaudits of both Winston Churchill and Josef Goebbels; enter Mrs. Miniver. The former British Prime Minister once claimed that Mrs. Miniver did more for the war effort than a fleet of destroyers, while the infamous Nazi propaganda minister demanded his own wartime filmmakers come up with something as brilliant and effective as Wyler’s family melodrama. It was this wartime propaganda film, following the lives of an affluent Kent family struggling through the war at home, that elevated Wyler to the upper echelons of Hollywood. Born in Alsace-Lorraine, the director was acutely aware of the threat posed by Hitler long before his peers in Hollywood were acknowledging it, and weaves those sentiments so effectively throughout every moment of Mrs. Miniver. It won him Best Director for the first time, and became the first of three Best Picture winners he would go on to direct, a record that still stands today.

Although its overly sentimental tone may feel a little on the nose nowadays, it’s just so brilliantly made that it’s hard not to still be charmed by it, and swept up in its support for the Allied cause. Few Wyler films, and indeed few films from the 40s, had the cultural impact of this one (the final sermon that closes the film was even printed onto leaflets and airdropped over occupied Europe). It opened up the American public to the struggles in Europe, bolstering support and providing hope while still being an incredibly entertaining drama.

Spending time with these characters is an absolute pleasure, brought to life by one of the finest collections of performances Wyler ever had. Greer Garson and Teresa Wright won Oscars for their work, but everyone impresses. Their moments of happiness fill you with joy, and their tougher moments ground you with them in their struggles and the times they are living through. There’s something comforting about seeing a family presented without any personal conflicts – no suspicion or lack of trust.

The film is more concerned with their perseverance through hard times, the ‘Keep Calm and Carry On’ mentality so often associated with this period of British history. The war is literally on their doorstep, and Wyler doesn’t sanitise any of the effects it has on the ordinary people just trying to get by (while still poking some fun at the upper class). Wyler’s use of space is magnificent, utilising every possible corner of the frame to make even simple conversations riveting to watch. His whole pacing of the story is perfect, weaving a soothing tapestry of idyllic life before completely pulling the rug out from under you with the final third. It’s emotional storytelling at its absolute finest.

4. Ben-Hur (1959)

Until James Cameron came along with Titanic, Ben-Hur had stood alone for nearly four decades as the film with the record for the most Oscars. Winning a whopping 11 of its 12 nominations, including Picture, Director, Actor, Supporting Actor, Production Design and Cinematography, it remains one of the grandest spectacles Hollywood ever produced. The story of Ben-Hur is one that studios have frequently retold, but it’s the 1959 epic that is universally considered the definitive version. Wyler was a veteran of the game by then, having over two decades of hit after hit, and it was Ben-Hur that earned him the unprecedented distinction of being the only director with three Best Picture winners under his belt.

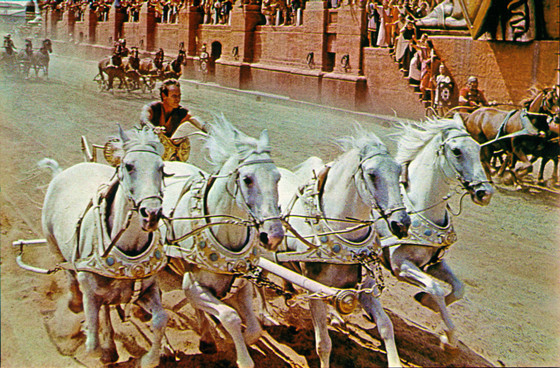

In an era when sword-and-sandal epics dominated the mainstream box office, Ben-Hur was the standard to beat. It’s epic in every sense of the word, a tale of brotherhood and betrayal set against the backdrop of the all-conquering Roman Empire and the preachings of a simple carpenter in Jerusalem. It’s a creative tour-de-force, with enormous sets and a sense of scale that trumps just about other film from the era for sheer immensity. The visuals alone are astounding – when you talk about the money being on the screen, nowhere is that more evident than in Ben-Hur (the chariot race arena alone took a year to carve out of stone).

Amongst all that size and spectacle, Wyler never loses his focus for a second, providing some thrilling sequences and an emotionally investing story. Imposing performances make the characters feel distinct (for the most part, Hugh Griffith’s Oscar winning brown-face role is particularly distasteful to modern eyes, and one of the Academy’s more shameful moments). It’s best remembered for the thrilling chariot race, one of the most visceral, tightly edited sequences ever put to film, but there’s plenty of other outstanding moments too. Giant warships, vast deserts, Roman forums and Biblical events are all brought to the screen with glistening precision and dazzling brilliance. Some of its religious messaging is a bit on the nose, but the way it’s all filmed is just too impressive to not be swept up by it.

3. The Best Years of Our Lives (1946)

Perhaps the most relevant film the director ever made, this was the first film Wyler directed post-WWII. Having spent the previous three years enlisted in the military and shooting some really groundbreaking war documentaries, he returned to studio filmmaking with a subject he and the rest of America (and indeed the world) were all too familiar with – war veterans returning home and readjusting to normal life. It immediately struck a chord with audiences, providing not just an entertaining family drama, but also a powerful message that almost every family at the time could relate to. This isn’t so much about the sentimentality as Mrs. Miniver was, but rather a thoughtful examination of life in a post-war world. It dominated that year’s Oscars, earning seven statues including a second Picture and Director for Wyler.

His image of postwar America, and the experiences of the returning soldiers, is as poignant as it is masterfully crafted. Drawing on his own experiences of returning from the war, the director uses the lives of three characters and their families to address the many problems faced by Americans at this time. He shows how they struggle to come to terms with the realities of returning to a class system, as well as their own physical and mental traumas. The military life is long gone, and with it the meritocracy that allows any man to rise up through the ranks; they find an America that is more confusing than the one they left, and one that seems to care little for their experiences. The deep focus cinematography and precisely orchestrated conversations reveal all of the fear and pain the characters cannot articulate.

The film’s whole design stresses the normality of everyone; there is nothing flashy or overly stylish about any of it, with sets and costumes that look well worn and lived in. This feeling grounds the story; it is through the bonds of family and friendship that our heroes are able to find some kind of peace in a world that will never be the same for them. It’s oddly prescient for a film made so soon after the war, capturing the mood and feeling of a nation while GI’s were still in the midst of returning from service. The film explores trauma, divorce and disability (disabled war veteran and non-professional actor Harold Russell gives a commendable Oscar winning performance) that no doubt impacted families all across the country, and they’re portrayed with honesty and sympathy. There’s little Hollywood manipulation going on here.

Wyler himself suffered the loss of most of his hearing while abroad, which only heightens the sense of respect with which he shows these struggles. Where Mrs. Miniver was instilled with the courage and determination of the mid-war years, The Best Years of Our Lives is tinged with more melancholy and weariness. On top of earning Wyler critical acclaim and accolades, both films serve as lovely bookends to the director’s WWII experiences.

2. The Heiress (1949)

Wyler had a knack for mining every ounce of subtlety and nuance out of his stars, and this was never more tactfully handled than his riveting 1949 drama The Heiress. Adapted from a play by Rufus and August Goetz, which was itself based on the Henry James novel Washington Square, it became a star vehicle for screen legend Olivia De Havilland, coming in a wildly successful run for her following her return from a blacklist in 1946.

It earned universal acclaim for both its star and director, closing out an immense decade for Wyler, cementing De Havilland as one of the top stars of the time, and winning her a second Oscar in the process. Her win is thoroughly deserved; she’s painfully naive and sympathetic as Catherine Sloper, before a bitter descent into a steeliness as she steps out of her privileged, coddled life and into the real world. Her expressive eyes, her slight facial twitches, her stiff body language – it all reveals so much depth to her character, and Wyler makes each and every moment as effective as possible.

His meticulously designed long takes are captivating, with slight eye movements and a characters’ line of sight telling just as much of the story as the dialogue. The man was a master of staging, and uses the spectacular 19th century mansion setting to terrific effect. It has some of the best examples of common motifs throughout his entire filmography – clever use of stairs and mirror shots to convey the story themes and character development. He knows just when to focus on a character long enough to make you think twice about them, maintaining a very slight tension throughout every interaction that keeps you glued to each moment.

Edith Head’s costumes are also wonderful, earning the legendary costume designer the first of her eight Academy Awards. They lend an elegance to every scene, making the characters feel authentic in spite of the obvious Hollywood melodramatic touches. Wyler covers the whole story with a sly, entertaining veneer of formality. The characters speak so precisely, and social faux-pas are always handled in a very proper and polite way, with the deeper feelings found in the subtleties of each performance. Every member of the small cast is superb. It’s one of the finest collections of performances the Golden Age ever produced, with De Havilland as the shining jewel at the centre of it all.

1. Roman Holiday (1953)

Of all the films he produced throughout his long and varied career, Roman Holiday has had the most staying power. Still regarded as one of the defining romantic comedies of Hollywood’s Golden Age, it perfectly captures the magical essence of what the genre is about. Nowadays rom-coms are frequently and rightly derided for lazy comedy and contrived scenarios. When smart, original examples are so few and far between, it’s easy to forget there was once a time when rom-coms weren’t just universally popular with audiences, but critical darlings too. They would frequently earn multiple Academy Award nominations, and were helmed by the biggest names in the industry.

Roman Holiday was the perfect combination of everything that can make the genre so wonderful. It’s a romance in a class of its own – a modern fairytale where true love is stumbled upon, and a princess’s kiss can transform a slimy frog into a handsome prince. Full of charm and wonder, and shot through with heartfelt poignancy, it’s a story that’s passionate, spontaneous and exciting, whether we are discovering it for the first time or eagerly waiting for all the best moments (which would be all of them). Rarely has romance been this graceful, and the two lead stars encapsulate that perfectly.

Of all the stars Wyler helped to create, none are as effortlessly magnetic as Audrey Hepburn. Her breakout role in Hollywood catapulted her into superstardom, earning her an Oscar and making her the most sought-after actress of the 1950s. She brought her distinct style to the role of Princess Ann, charming audiences with her gracefulness and easy chemistry with Gregory Peck. Peck famously insisted that Wyler put Hepburn’s name alongside his own on the poster, so convinced was he that she would become a star and win the Oscar.

In a story of self-willed liberation, Hepburn is a personification of loveliness. Naive and kindhearted but with a strong will and determination, she plays it all with such a genuine wide-eyed wonder that you have no trouble believing she is seeing the hustle and bustle of Rome for the first time in her life. It’s an infectious delight to spend time in her company. Like a coming of age film, she embarks on an adventure into the great unknown, and returns to her duty as a stronger, wiser person. That sense of duty, to her position and to her people, is never forgotten either, and builds to one of the most finely crafted, agonising finales in any rom-com.

Opposite her, Peck could be straight out of a film noir, so crummy and desperate is he to begin with. Slowly he is changed and charmed by his experiences, his expressive eyes conveying affection, excitement and empathy bubbling beneath the surface. The two have a real magical, enduring connection and the whole film rests on the ease with which they play it.

Wyler’s careful touch is apparent in every scene, moving things forward at pace. His legendary perfectionism is lightly worn, each shot controlled and precise, and infused with genuine warmth. In a filmography full of technically brilliant films, it’s easy to overlook the meticulous craft at play in Roman Holiday. Equally at ease with contemporary locations and designed spaces, Wyler creates a world that is energetic and of its time, and yet still timeless. This is only enhanced by the black and white cinematography, which entrances and lends the story a further time-honoured quality. Rome brims with life, history and adventure. It’s a fairytale as old as time, all wrapped up in a glistening Hollywood production – an eternal story for the Eternal City. This royal romance is the crowning glory in Wyler’s extraordinary career.