8. The Driver (1978)

Good as “Streets of Fire” may be, however, it still pales in comparison to Walter Hill’s magnum opus: “The Driver.” A quiet but hugely influential film, “The Driver” is not often cited as one of the seminal ‘70s New Hollywood movies, but it should be, since its impact reaches far and wide among generations of filmmakers.

Notoriously, it was the main inspiration behind Edgar Wright’s “Baby Driver” (as well as another recent and popular car movie we’ll talk about in a second), but traces of Hill’s visual style can be found even in the work of titans of American cinema, like James Cameron and Michael Mann. The way the car chases are shot and lit in the first “Terminator” are directly indebted to this film, as is Mann’s sensibility in the telling of stories about professional men in both sides of the law, with strict codes of conduct, playing games of chance in an attempt to connect and escape the loneliness their code and competence imposes on them.

What’s most surprising about “The Driver” is how it’s still visually striking, even despite decades of imitation: the green neon that lights nighttime LA looks utterly stunning, as does the clean, geographically sound chase scenes that set the bar for what would come next. Clocking in at less than 90 minutes, it’s the platonic ideal of a lean and mean crime movie, the kind that merits that old label of “they don’t make ’em like this anymore” – at least not with this level of skill.

7. Drive (2011)

A movie not so much inspired by “The Driver” as much as it is a spiritual successor to the 1978 classic, Nicolas Winding Refn’s “Drive,” in the last 10 years since it took the film world by storm, has remained basically unblemished, despite the dwindling reputation of its director, whose subsequent efforts failed to capture the same hold of public imagination as this, his mainstream breakout.

It’s true that Refn’s movies (and his miniseries) have since gradually fallen deeper and deeper into the hole of his private obsessions, becoming oblique style exercises disengaged from regular narrative concerns. But even if that wasn’t the case, it would be too much to expect for the filmmaker to achieve again the perfect storm that is “Drive”: a mix of hyper-violent homage to ‘80s genre fare with romantic drama, featuring a brilliantly crafted character at its center, who miraculously toes the line between relatable vulnerability and quasi-mythical hero iconography (who can forget that scorpion jacket?).

Most importantly, all of that is delivered via absolutely impeccable craft, by a crew of artists who deeply understand the genre in which they are working, managing to distill an entire era of filmmaking to its essential stylistic elements, honoring everything that made those ‘80s classics special. Cliff Martinez’s incredible synth score and Refn’s meticulous framing allied with Newton Thomas Sigel’s irresistible neon lighting all work in perfect unison to move “Drive” beyond mere pastiche into a work with ample personality of its own. It’s the extremely rare case of a modern neon-noir that gets everything right – the kind that only comes once in many years. It’s already been 10 since this movie came out, so let’s hope another one is just around the corner.

6. To Live and Die in LA (1985)

There are many movies that use the alluring veneer of noir to seduce the viewer into its world of violence, and sex and decadence as an excuse to explore larger themes (the aforementioned “Strange Days” being a perfect example) – and then there are some movies that are simply pure, unadulterated, shameless pulp, content to swim in the shiny surfaces of the genre and explore it for all its decadent glory.

William Friedkin’s “To Live and Die in LA” is one such case, one of the single greatest style exercises ever made; a relentlessly nasty and exciting cop film that miraculously avoids going full copaganda, as so many other ‘80s buddy movies do, thanks to Friedkin’s frank misanthropy that puts the alleged heroes in equal footing of violence and cruelty with the fantastic villain played by Willen Dafoe.

The film is everything a genre fiend could ever hope for: highly stylized ultraviolence; a magnificent ‘80s synth score; high wire car chases; and, of course, the obligatory neon drenched environment of Los Angeles, that may never have looked so dangerous and desolate on film ever again.

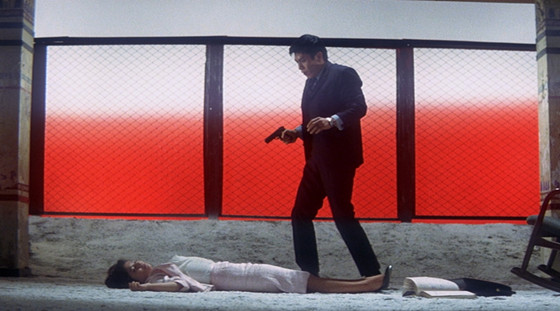

5. Tokyo Drifter (1966)

Pop art meets noir, by way of the yakuza movie, all channelled through ‘60s absurdism and surrealism – there’s an infinite number of labels one can put on “Tokyo Drifter” to try to achieve some kind of known definition for Seijun Suzuki’s unparalleled alchemy of genres.

What category to fit the movie into, however, is a much less important matter in comparison to the brilliance of the work itself. The culmination of a decade’s worth of increasingly avant-garde crime movies from Suzuki, who had been, with each new feature, not so much pushing as exploding the boundaries of what a yakuza movie could be, “Tokyo Drifter” finds the director in the prime of both of his artistic ambitions and the ability to pull off his wildest visual ideas (in spite, or maybe precisely because of, pushback from the studio, who cut down the budget in a effort to discourage him from pursuing his surreal style).

The resulting film is a strong contender for the most consistently aesthetically pleasing movie of all time, featuring hall-of-fame cinematography and production design; every single set featuring a lavish color scheme wouldn’t be out of place in a MGM musical, which offered Suzuki the opportunity to indulge in his meticulously composed shots and theatrically exaggerated shootouts.

In fact, the look of the “Tokyo Drifter” is so utterly indelible that the plot itself is deliberately made to be scattered and even difficult to follow, not to distract from the real purpose of the film – to drink in the remarkable images. If the viewer is willing to accept that, they’ll have a wonderful time.

4. Manhunter (1986)

The very best modern noir director (sorry, Johnnie To), Michael Mann has worked within the archetypes and aesthetic style of noir for pretty much his entire career – and, really, almost all of his movies would be at home in any “Best Of” noir lists. Some, however, are more specifically situated among certain subgenres and, as far as neon-noir is concerned, Mann is responsible for two of the very best.

One is “Manhunter,” Mann’s adaptation of the Thomas Harris novel that first introduced the world to Hannibal Lecter, and would later be adapted again into another movie (“Red Dragon,” directed by Brett Ratner) and a season-long arc in the TV show “Hannibal” – a fact worth mentioning because it presents a fascinating case study in the role a director has in shaping a movie and truly making it what it is. All of these adaptations are fairly faithful to the book, changing only peripheral details but maintaining the exact same structure, characters, main plot points, and most important scenes (the “do you see?” sequence being virtually the same, in terms of content, in all versions).

How come, then, all of these versions, having basically the same exact story, are so different in terms of atmosphere, style and, most importantly, quality? The answer is obvious: the director. People who keep tooting the horn of “story” as being the single most important thing in cinema demonstrate a profound lack of understanding of how the medium works as a whole, but also of what makes individual movies great, since it’s that single directorial vision that guides everything else and is ultimately responsible for the finished work.

Mann’s vision of the material, of course, is superb, mining all the latent psychological darkness of the novel and bringing it to the forefront, whilst also indulging in the procedural elements with his typical obsession for verisimilitude and detail. Needless to mention, also, the spectacular stylistic flourishes that transcend the material and elevate it into purely cinematic territory (something that eluded other adaptations).

3. Thief (1981)

“Manhunter” was the triumph that confirmed Mann as a peerless chronicler of male angst and as a master of crime dramas, but the movie that first announced the arrival of a major American auteur (and which, in many ways, remains the superior film) was “Thief.”

There are many examples of terrific debuts by people who would eventually go on to cement their places in the pantheon of great directors, but a much rarer thing is for a director to break into the scene with a fully formed style. Such is the case of Mann, who, despite having previously directed a made-for-TV movie called “The Jericho Mile,” debuted on the big screen with “Thief.” It is, in every way, the work of a mature artist already with very specific obsessions and also in complete control over his medium: the tale of methodical criminals, their desperate female partners, and the unforgiving underworld that engulfs and ultimately destroys their love, themes that Mann would incorporate in basically every single one of his subsequent crime movies, were already explored with vivid gusto in his first film.

Even more impressive than that, however, is Mann’s instant dominion over craft: there are some who can beat him as far as stylization or gritty realism goes, but there is absolutely none who can match those two things together more seamlessly than him. Mann’s brand of neon-noir is one that simultaneously indulges in the surface pleasures that crime dramas can offer (his heists are always thrilling, the ever-present green neon shades always beautiful) but also emphasizes the inherently dark underpinnings of the crime world, in vivid detail.

2. Blade Runner (1982)

By the time Cameron coined the term “tech-noir” for himself, it was already too late: the absolute epitome of the style he was trying to describe had already come two years earlier, in the form of “Blade Runner.”

An obligatory entry in almost every list ever made of the best neo-noir movies, Ridley Scott’s magnum opus fits much more comfortably in the neon categorization of the genre, considering the director’s vision of a bleak retrofuturist world filled with gigantic neon led screens, a melting pot of different cultures merging in the chaotic design of the urban landscape, lensed through high contrast but colorful cinematography. All of that has come to be shamelessly copied to the point of becoming commonplace – proving the movie’s status as an essential, almost sacred visual bible of how to do neon-noir right.

Even still, nothing, not even the very best efforts at homage or theft (consider Spielberg’s “Minority Report” or even Villeneuve’s sequel) come close to achieving the originality of vision and the virtuoso formal control of the original “Blade Runner” – only an unimpeachable masterpiece could’ve survived so many years of debate, copies, parodies and recuts (Ridley’s own fault, this one, but we can forgive him that).

1. Taxi Driver (1976)

What is there left to say about “Taxi Driver,” really? Decades of endless analysis, debate, and downright dissection have explored almost every conceivable aspect of the film, aesthetic, narrative, thematic and otherwise – and still have not yet exhausted the richness of Martin Scorsese’s all-time masterpiece, for, like all great works of art, one can have a deeply personal response to the movie that is independent both of the original intention of the artists and of the consensus achieved by the critical intelligentsia.

So, for the purposes of this list, let us simply assume that you’ve heard over and over again the typical talking points regarding Robert De Niro’s performance; the exploration of themes such as loneliness, alienation and racism; the ambiguity of the ending, and so forth. We’re all aware and in agreement. Let’s instead focus on the aspect of “Taxi Driver” that landed it on this list: Scorsese’s and Michael Chapman’s vision of New York City as a neon hellscape. Or rather, Travis Bickle’s vision, since the camera is merely a vessel for his subjective point of view – one of the most impressive instances of the subjective perspective in the history of cinema.

The further the character’s mind slips into his own distorted views and prejudices, the more the image of the city around him, which he deems responsible for all evil in the world, twists into a inescapable landscape of social apocalypse, filled with underage prostitutes, unrepentant pimps, and homicidal husbands – all living under the same hellish red neon light that punishes Bickle’s weary and furious gaze every night.

It’s a miracle of visual storytelling, communicating not concrete information about the plot, but something much more ethereal and hard to convey – a person’s state of mind and emotional turmoil. In that way, it has no equal in the realm of neon-noir.