6. The Conformist (1970)

When asked about her favorite filmmakers, Campion mentioned Italian maestro Bernardo Bertolucci among those whom she personally feels she pays back with her own work. “I suppose because I have always admired directors like him, there’s a part of me that wanted to do that type of film too. It’s not that I don’t mind an occasional stupid movie. I just don’t want to make them.”

Toxic masculinity is a strong undercurrent woven indispensably into Campion’s thematic fabric. One of her strengths comes from how she crafts multilayered characters that defy a simple label of ‘good’ or ‘evil’, but rather fit into a more nuanced scale of moral grays. Bertolucci’s film probes into similar ground by exploring the frail ego of Marcello Clerici, a sexually repressed man who becomes Mussolini’s errant boy in fascist Italy.

The story weaves through Marcello’s early life through a series of flashbacks, painting a portrait of an utterly insecure man who acts not out of true conviction but as a means to fitting in in society, whether it’s taking out political dissidents for the National Fascist Party or marrying a young woman for social clout. The Conformist never deals in platitudes, but the film does work as a cautionary tale of how ideological extremism preys on the weak and how turning a blind eye to intolerance brought these authoritarian regimes to power in the first place.

7. La Strada (1954)

Women always seem to get the short end of the stick in Campion’s films, where they’re subject to an array of misfortunes, from personal losses (An Angel at My Table), social alienation (Sweetie) to marital abuse (The Piano, The Portrait of a Lady). Taking that into consideration, it isn’t hard to see why something like La Strada would strike a chord with the Kiwi filmmaker.

A benchmark of Italian Neorealism, the film centers around a simple-minded woman who upon being purchased by a ruthless circus strongman, has to endure unthinkable abuse and hardships as they roam around the Italian countryside performing shows together. Her tragic story serves both as a bleak snapshot of a rural Europe still reeling from World War II, and as a poignant call for empathy.

“La Strada is quite perfect — a haunting film for all time. Fellini is a deep, deep master of film.”, claims Campion. She considers the Italian master to be the most fluent filmmaker ever, praising among other qualities his elegant storytelling; “it’s as if he’s thinking his shots through a camera in his mind and straight onto a screen. As time goes by, I adore him more and more, and his legacy appears more remarkable and incomparable.”

8. L’Avventura (1960)

One defining trait of Jane Campion’s brand of filmmaking is the way she refuses to openly spell out its themes or spoon-feed her audience. Her stories seem to consist of narrative drift all but shrouded in ambiguity, where backstories and past traumas are only hinted at but never fully explored. On the whole, she’s proven to be far more interested in showing than telling, in the same way that traditional narratives often take a backseat to her characters’ inner turmoil.

In that regard, L’Avventura is cut from the same cloth as most of Campion’s work. The film is the first entry in Michelangelo Antonioni’s trilogy on modernity and its discontents, a thematic triptych that mirrored the generational ennui and social alienation of its time, while raising lofty questions about tradition, capitalism and humanity in postwar Europe. Granted, L’Avventura offers no such thing as a strait-laced plot, but the story centers around the puzzling disappearance of a young woman during a trip to a remote volcanic island. In a similar way to how Campion never reveals the reason behind Ada’s muteness in The Piano, L’Avventura never brings closure to its central mystery. The crux of the film lies elsewhere; most evidently in mapping the thorny romance between Anna’s fiancé and her best friend against the aftermath of her tragic vanishing.

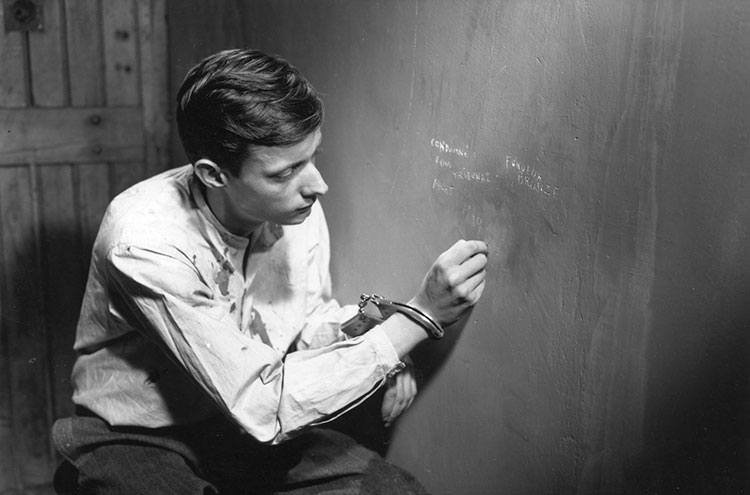

9. A Man Escaped (1956)

Campion claims that she had a ‘big rethink’ on how she wanted to do things during the long career gap that preceded Bright Star, her 2009 Victorian-era romance. “I had always tried to funnel people into a place where they had no choice, and people didn’t like that”. So the Australian director decided to go “as simple as possible, rather than showing off” with her next project. To accomplish that, she went back to basics and meticulously studied old films she had first discovered as a student.

Robert Bresson — a French director widely renowned by his rigorous asceticism — is credited as her biggest inspiration going forward. A Man Escaped is often hailed as his crowning achievement; a nail-biting tale of resilience and human willpower that chronicles the prison escape of a French Resistance soldier during Nazi occupation. “The film is so simple, so tense, you believe every moment. I guess I had distrusted the kind of simplicity so much that watching it became truly riveting for me”. Campion commended Bresson’s classic for exuding a “sense of deeper trust when you’re not being emotionally manipulated”, something she prides herself in emulating with her own work.

10. Dead Man (1995)

A big reason behind The Power of the Dog’s critical reception stems from the way it used one of the most familiar templates in cinematic lexicon, the western genre, and proceeded to dodge clichés by upending every generic convention audiences have grown to expect. Dead Man is a film that operates on a similar wavelength as an existentialist thesis delivered in the guise of a turn-of-the-century western that results in a refreshing new take that is thoroughly its own thing. Broadly put, the film follows the spiritual pilgrimage of a guilt-ridden accountant, William Blake, who befriends a native American that helps him prepare for his journey as he leaves this realm onto the next one.

This is not the first time that Campion has earned comparisons with Jim Jarmusch. Her transgressive debut (Sweetie) was linked to Jarmusch’ idiosyncratic style for its leisurely pace and inscrutable thematic punches. For Campion, any resemblance is taken as a compliment. “I am very openhearted when it comes to filmmakers that have deeply influenced me”. The thing that resonates most for her about Jarmusch is that his stories are “really interesting” and boil down to “simply being human”. Though admittedly, that could also be said about hers.