6. Tower (2016)

Taking rotoscope animation into the realm of the documentary film, “Tower” follows the story of the 1966 University of Texas shooting spree from a clock tower in central Austin. The shooting lasted 96 minutes and claimed at least 45 victims, including 14 deaths and 31 injuries (one of whom died later from complications related to the injury). The incident was highly televised, and when the police were finally able to fire back at the shooter and kill him (with the help of a deputized citizen and others providing ground support), investigators learned the man was Charles Whitman, a young veteran who had killed his wife and mother before arriving at the tower. The film mixes archival footage of the incident with well-traced and realistic rotoscope animation of dramatized events, recounted interviews, updates and other related sequences to tell the story in a new way, and to a new audience.

While the animation style of “Tower” remains fairly consistent throughout the film, the shading and color can vary considerably from one scene to the next, including black-and-white scenes to match the period’s news footage and both full-color and partial-color sequences as the story develops. These shifts in color and shading are effective ways to create tension and isolate characters at the center of the action. While the combining of archival footage with rotoscope and other forms of animation has been used in the past, “Tower” stands out as an exceptional film that merges classic and modern styles to add fresh perspective to a highly relevant historical moment.

Directed and produced by Keith Maitland, “Tower” is one of many recent animation projects developed by Minnow Mountain studios, a company that routinely uses its unique style of rotoscoping for both film and television. One of the founders of Minnow Mountain, Animator Craig Staggs worked with Richard Linklater on “A Scanner Darkly” and helped to innovate what the company calls “performance-capture rotoscope,” a hybrid approach similar to Linklater’s interpolated format. Linklater partnered with Minnow Mountain for his most recent film, “Apollo 10 ½: A Space Age Childhood.”

7. Tehran Taboo (2017)

A film about cultural taboos, “Tehran Taboo” tells the story of both women and men who clash with local mores in their search for a better life. The first feature-length film by Iranian-born German Filmmaker Ali Soozandeh, “Tehran Taboo” uses rotoscoping in part due to the limitations of filming in Tehran. Due to Iranian censorship laws, many of the film’s subjects are far too revealing for on-location filming, making rotoscopy and animated backgrounds an attractive option. Yet despite Soozandeh’s initial plans for a live-action film, the animation style he adopts is highly innovative, attractive and at its best moments, mesmerizing. Like “Tower,” mentioned above, “Tehran Taboo” uses alternating color schemes but with more vibrant, high-contrast tones. Characters truly appear as if they are in the Tehran environment and interacting with their settings.

According to Soozandeh, one of the primary advantages of using the rotoscope method is its ability to capture the performances of the actors, and in “Tehran Taboo,” this is extremely important, as the high level of realism preserves the details of each actor’s expressions, body language and mannerisms. In a setting in which men and women are not allowed to speak to one another in public, this attention to detail is crucial for character interactions and plot development. Working in front of a greenscreen can be challenging for actors, but in this case, those involved were very familiar with Tehran and its unique identity and culture, and their performances are convincingly honest. While “Tehran Taboo” deals with some rather dark areas of human cruelty and suffering, it is also about love, friendship and what it means to be part of a community that appears, in some ways, to be working against you.

8. Loving Vincent (2017)

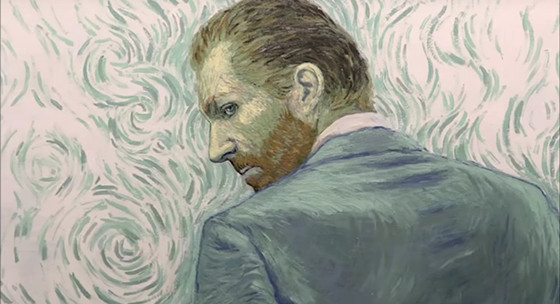

Taking rotoscope in a new direction, “Loving Vincent,” written and directed by Dorota Kobiela and Hugh Welchman, is a film about Vincent van Gogh that is hand painted in the style of his famous works. Using an experimental process, the filmmakers hired classically trained oil painters, rather than animators, to paint over every frame with Van Gogh’s characteristic impasto style. Over 100 painters in several countries were hired for this process, taking them six years to complete 65,000 paintings, each of which was broadcasted onto an actual canvas. Welchman, the director, jokingly referred to the process as “the slowest form of filmmaking ever devised in 120 years.” But the result is quite unique for an animated film, and like Van Gogh’s work, its colors, proportions and brushstrokes are highly expressive and a pleasure to view throughout the film’s 95 -minute run time.

Starting as a short film in 2008, “Loving Vincent” examines Van Gogh’s death and the circumstances leading up to it. The story takes place roughly a year after the artist’s death when a postman’s son named Armand (Douglas Booth) investigates some of the mysteries surrounding the artist’s final days. While Van Gogh’s institutionalization and preceding acts of self harm are well documented, a lot about the artist’s life, and especially his death, remains a mystery. This film takes a fresh look at those questions in a world shaped and colored with the man’s iconic form of expression. Every scene is full of intense color and light, along with plenty of textured contrasts and atmospheric swirls, and while Van Gogh himself is not the main character, but rather, the subject of an investigation, he is present in spirit as well as in flashbacks.

“Loving Vincent” won the Best Animated Feature Film Award at the 30th European Film Awards and was nominated for Best Animated Feature at the 90th Academy Awards. Its writer and creator, Dorota Kobiela, is now working on a painted-rotoscope adaptation of the Polish novel “The Peasants,” by Władysław Reymont, first published from 1904 to 1909 as a serial.

9. I Lost My Body (2019)

Likely the first and only film to portray a severed hand as a central character, “I Lost My Body,” directed by French filmmaker Jérémy Clapin, is much more than a summary description might suggest. Based on the novel “Happy Hand” by Guillaume Laurant, “I Lost My Body” uses a composite style of animation that incorporates rotoscoping in some scenes more than others. For example, no source footage existed for the animated severed hand, which had its own personality and many scenes on its own. And while tracing was used for characters as well as their settings, animators added expressions and details for a more traditional presentation. Like the work of Linklater and Minnow Mountain, this film’s animation is a composition of digital and hand-drawn forms, though it is arguably more heavy-handed, so to speak, in its embellishments and final design.

“I Lost My Body” received numerous awards and nominations and was the first animated film to win the Cannes Film Festival’s Nespresso Grand Prize during International Critics’ Week. Critics praised its animation but also its inventive and surprisingly emotional storyline. The severed hand in the film is an escapee from a post-op laboratory refrigerator, and it’s willing to crawl on its fingers across the suburbs of Paris to find the person it belongs to. Told through a series of flashbacks that appear like memories of the hand’s former life, the story of the man who lost the hand begins in the days before the accident, eventually building up to the present as the two narratives become one.

This dual-narrative structure is further complemented by the shifts in animation style between scenes of the hand and those of its previous owner, a distinction that also merges in the end. “I Lost My Body,” like many films on this list, would be much less intriguing as a live-action or strictly animated feature. The balance of traditional art forms with the hyper-lucid clarity of digital film is a critical component of the world building that exists at the heart of the film’s narrative framework, and it’s the validity of that world that keeps audiences watching, and caring. The world created by the animators of “I Lost My Body” is so well crafted that audiences not only suspend their disbelief of living body parts, but they’re likely to empathize with the appendage as if it were no different than any other character in film (which it isn’t).

10. The Spine of Night (2021)

A film for diehard rotoscope traditionalists, “The Spine of Night,” directed by Philip Gelatt and Morgan Galen King, is a dark fantasy film with a retro-’80s luster and deep philosophical undertones. Fans of Ralph Backshi and films like “Heavy Metal,” Philip Gelatt and Morgan King created “The Spine of Night” after the success of King’s short film project “Exordium” in 2013. Like “The Spine of Night,” “Exordium” before it was hypnotic, hallucinatory and violently beautiful, inspiring fans to call for a full-length version to expand on the original idea. It was a considerable undertaking at the time, but Gelatt and King remained persistent through seven years of filmmaking to realize their dream.

These filmmakers spent the majority of their time, money and effort through years of development and production. With nothing but a warehouse, a small crew and some rotoscope software, they managed to create a breakout independent hit that is quickly becoming a cult classic among fantasy and animation enthusiasts throughout the world. While advances in technology have allowed for cheaper and easier film productions, it is still quite a feat for a pair of filmmakers to create a successful full-length animated feature on a limited budget, and it’s especially challenging for a film that is rotoscoped at 12 frames per second. And despite the film’s limited budget, the directors were able to cast mainstream actors such as Richard Grant, Lucy Lawless and Patton Oswalt, in part due to the enthusiasm gained from the original short film, which is viewable for free online.

“The Spine of Night” screened at numerous film festivals, including South by Southwest in the U.S., and for the most part audiences have been passionate about the rotoscope aesthetic and appreciative for what these filmmakers have accomplished. Though some critics have called the film a “throwback” to an earlier style, others have admired its purity of form, giving it due credit for authenticity and, perhaps more importantly, acknowledging its rotoscope medium as a hallmark of artistic devotion.