Paul Verhoeven is undoubtedly one of the most transgressive artists ever to have been a major Hollywood player; a genius satirist and a master craftsman of spectacle; a pervert with never-ending interest in sexual mores and a populist who makes grand action extravaganzas designed to be enjoyed by all; a funny man who deals with the most serious of social subjects.

This contradiction in his style are exactly what makes him such an essential filmmaker, a perpetually controversial and misunderstood director that’s always ahead of his time – is there anyone else whose work has so often been derided upon release only to be reappraised years later when the world finally catches up?

16. Business is Business (1971)

The level of interest one might have in “Business is Business,” Verhoeven’s feature debut, depends entirely on perspective. Taken on its own, it’s admittedly far from a great movie, but if seen as an hors d’oeuvres to this director’s style, it’s fascinating.

Some of the major themes Verhoeven would spend the rest of his career obsessing over are already present here, mainly sexual desire and its intersection with capitalist exploitation; all filtered through his sardonic sense of humour, which was also noticeable from the get go. In fact, “Business is Business” is one of the few outright, straight comedies he ever made, and while it is a frequently funny movie, it never comes close to reaching the heights of the acidic satire that defines his best efforts.

It’s precisely in that way that the movie is both frustrating and exciting; the former because it doesn’t manage to coalesce to become more than the sum of its good individual parts, the latter because, despite that, it does offer glimpses of the birth of a major cinematic voice.

15. Hollow Man (2000)

Verhoeven’s last American film before his creatively invigorating return to Europe, “Hollow Man” is easily the worst of his Hollywood phase; which is not to say that it’s a bad movie by any stretch – it just pales in comparison to the brilliance of his other features of the era.

It’s easy to point out what is wrong here, why this movie in particular is so inferior to Verhoeven’s previous output, since the director himself has explained it. “I felt like I was doing the bidding of the studio. I couldn’t even put a personal touch to it. I fell into that trap,” he stated in a 2016 interview with Vulture. The filmmaker went on to say: “I felt that I did Hollow Man without making it personal. The studio wanted it this way. The freedom was gone.”

The experience was so clearly personally painful for Verhoeven that it colors his view of the final movie, which he hates and claims it’s the only one of his own pictures that he cannot defend. Thankfully, “Hollow Man” is not as bad as he seems to think, precisely because of how Verhoeven manages to push the classic “invisible man” premise into it’s filthiest, most violent possibilities; in it’s best moments the film becomes a nasty, vicious piece that the filmmaker is made for.

Unfortunately, those moments are mostly buried amid bland Hollywood cliches and tropes, so Verhoeven’s distaste is quite understandable.

14. Spetters (1980)

It’d be essentially impossible to be a squeamish, prude or overly moralistic person and be a fan of Paul Verhoeven; the joy and pleasure of his work lies precisely in the filthy extremes he’s willing to indulge; his shameless passion for the taboo and the unrelenting cynicism of his vision of humanity.

Verhoeven’s best movies combine their fun, pulpy sleaziness with a layered sense of self-awareness; he’s a provocateur, sure, but his finest work rises above mere juvenile titillation to provide thoughtful, complex commentary.

Which is why “Spetters” feels so frustrating; it’s the one film in which Verhoeven’s provocations feel completely empty, meant solely to shock, devoid of a larger satirical outlook. Transgression for it’s own sake has value, of course, but some sequences here (as a gay man raping a homophobic one, who apparently “likes” it) go beyond the usual “bad taste” of his work (that is ironic and self-reflexive), they’re genuinely ugly, juvenile stuff.

13. Katie Tippel (1975)

Verhoeven’s early Dutch phase is essential for understanding the tone, style and intentions of his later, more famous American films. Case in point: “Katie Tippel,” which deals in a more respectable, straightforward (albeit still very Verhoevian) way with many of the same themes the director would return to in the misunderstood “Showgirls.”

The way misogyny and class warfare intersects; the selling of a woman’s body being just another transaction in the capitalist world; the commodification of desire – it’s all here, as is the crude violence and sexual content. And yet, this film lacks something essential – ultimately, it’s just too polite, too clean in its style to fully drive home the point Verhoeven is trying to make.

The garish nature of his later American films is brilliant because it transforms the theme into form – the very aesthetic of the movies reflect the twisted worlds and warped morals portrayed in the stories. “Katie Tippel,” by contrast, while well-made and entertaining enough, lacks the full power of that satirical bite.

12. Turkish Delight (1973)

Released just two years after his underwhelming debut, “Turkish Delight,” Verhoeven’s second ever feature, marks a huge leap for the director in terms of personality, voice and strength of style – two movies in and he already starts to feel like an auteur.

But even in Verhoeven’s own oeuvre this film is unique, not necessarily in it’s kinkiness and blunt sexual content (a given in any Verhoeven film); but how it uses it’s gross explicitness (including extended sequences involving maggots, worms and rape) in order to create a genuinely sweet love story – a very eschatological one, for sure, but just as emotionally engaging as the finest screen romances.

“Turkish Delight” also marks Verhoeven’s first foray into camp (though not as fully fledged as his later movies) and already demonstrates his proclivity for wild tonal balancing – the film essentially plays like a romantic comedy until it’s harrowing final part. It doesn’t fully work yet as a whole, but it’s an excellent early indicator of a major voice.

11. Flesh + Blood (1985)

Verhoeven’s first English-language movie is as perfect a prelude to his Hollywood period as one could hope for; it basically encapsulates every single one of his thematic obsessions: stylistic predilections and auteurist traits in one supremely savage package.

It’s ironic, however, that “Flesh + Blood” is the film that ushered Verhoeven’s most successful era, considering it had a notoriously troubled production and was, upon release, a massive commercial disaster. That failure is both unfair and completely understandable; unfair because it’s a great movie that deserved recognition in it’s own time, but understandable because the picture’s upending of medieval adventure tropes is far too bleak and cynical to ever be broadly appealing.

“Flesh + Blood” is a film in which lovers plea eternal devotion beneath rotting corpses; innocent maidens get brutally raped; noble warriors give nuns lasting brain damage; mercenaries are considered prophets by priests and everyone eventually succumbs in the most gruesome, graphic ways to the plague. It is, in summary, an acidic portrayal of the Dark Ages that completely rebuts traditional morality and easy dichotomies of good and evil – in Verhoeven’s world the only imperative is survival and everyone is willing to do anything to stay alive and prosperous. Cynical but honest; and never anything less than engrossing drama.

10. Soldier Of Orange (1977)

In many ways Verhoeven’s most respectable, prestige film (so much so that it attracted the attention of Spielberg and George Lucas, even prompting the latter to offer him “Return Of The Jedi”), “Soldier of Orange” is a war epic that bridges the gap between the genre’s typical beats and uniquely Verhoevian quirks.

On one hand, the film delivers on the expected scope and pathos of a war picture, telling a sprawling story full of characters, spanning many years, and packing an emotional punch in its tragic developments. What makes the “Soldier Of Orange” distinct and memorable, however, are the ways in which Verhoeven sneaks his sensibilities in what is otherwise a very good but fairly standard film, the way he stages certain sequences for maximum violence and even humour (as the scene in which a man is killed while in the toilet).

And more than that, the movie is also one of the earliest testaments to Verhoeven’s technical mastery; then the most expensive Dutch film ever made, “Soldier Of Orange” displays every cent of that budget in its exquisite cinematography and sense of grandeur.

9. The 4th Man (1983)

At first sight, “The 4th Man,” Verhoeven’s last Dutch movie before venturing into English-language work, looks like just another one of the director’s quintessential sleazy erotic thrillers – and while it does work marvelously as that, the film is also a unique entry in his filmography.

While Verhoeven’s style is extremely heightened (both formally and dramatically), his work almost never reaches into outright surreal territory – even his most absurd premises and moments are grounded in some kind of internal logic and in the tangible reality of the worlds of the stories.

“The 4th Man,” by contrast, is a complete fever (wet) dream; disregarding any sense of realism for a dream logic that perfectly tracks the protagonist’s descent into madness.

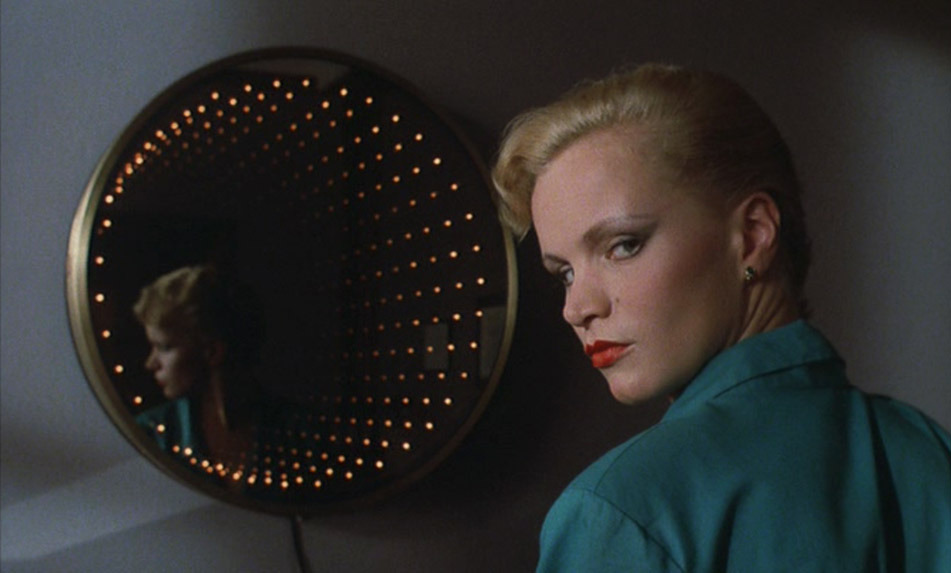

That sense of surrealism also works magnificently in tandem with Verhoeven’s treatment of noir atmosphere – here, every trope and archetype is pushed to its extreme, making what once was subtext explicit (in more ways than one). “The 4th Man” is a Hitchcockian thriller with any inhibitions taken off – a blast, from beginning to end.