The thriller is one of the most compatible and accessible genres in the medium of film. It complements films of all genres, including non-genre films, but they also work proficiently on their own. A plot can be extraneous when put through the wringer of a captivating thriller.

When done right, thrillers strike the perfect balance between thoughtful and engaging art and sheer entertainment. The idea of a thrill is inherent to the power of cinema. Many of the great films of the past and present contain thrilling elements, but there are so many hidden gems in the genre that inject viewers with adrenaline and conjure meditations on the human spirit.

1. Marnie (1964)

In the word association game, Alfred Hitchcock is paired alongside thrillers. The Master of Suspense pushed the boundaries of cinematic thrills for decades. His genius was through the psychological manipulation of the audience, constantly leaving them on ice. In 1964, what is now recognized as the end of a golden age for Hitchcock starting in the ‘50s, he directed Marnie, one of his most overlooked films and mentally taxing thrillers of his filmography.

In a familiar Hitchcock story, the titular Marnie (Tippi Hedren) experiences immense psychological traumas, and her husband Mark (Sean Connery) attempts to resolve her issues, even though his wife is a habitual thief. In terms of plotting, the film has a light grasp. Audiences are left to ride the waves of this tumultuous relationship. In the usual brilliant Hitchcock fashion, he maintains a strong viewer perspective on the various mental crises taken on by Marnie. The intense visual language of Hitchcock’s directing to exhibit her mental anguish is the closest the director has gotten to horror, even more so than Psycho or The Birds.

With this thriller, Hitchcock let loose his rigid structuring and allowed the trauma to guide the story along. Because of the emotional violence behind the suppression of trauma, Marnie is perhaps the director’s most harrowing work ever. The film represents Hitchcock at his most confrontational with his sexual perversions and examinations of the darkness of one’s soul. Connery’s character is a revisionist take on a Hitchcock protagonist, as his supposed heroism is immediately undermined by an inherent sense of paranoia. No MacGuffin or set piece is required, as psychological turmoil is thrilling enough as a dramatic device. All in all, Marnie is worthy of being placed highly in the Hitchcock canon.

2. Snake Eyes (1998)

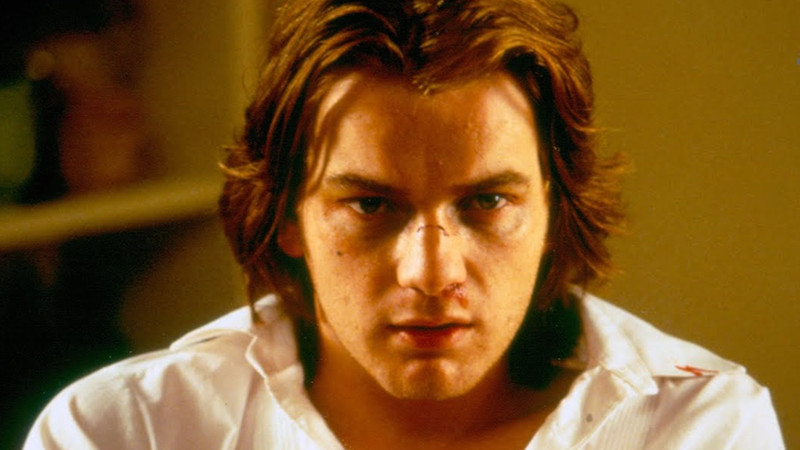

Commonly labeled, sometimes dinged for it, as the heir apparent to Alfred Hitchcock, Brian De Palma was New Hollywood’s master of sexually perverse, voyeuristic thrillers. His mechanical efficiency made his cinematic style feel lively and original even when his stories appeared to be redundant. After a decade of dabbling in new genres, De Palma returned to his roots in 1998 with Snake Eyes, a voyeuristic Hitchcock homage that is De Palma at his most maximalist.

A murder mystery set in Atlantic City, Snake Eyes depicts a shady detective, Rick Santoro (Nicolas Cage), who witnesses a political assassination at a boxing match and seeks to find the missing pieces and loopholes to the investigation of the perpetrator and greater conspiracy at large. Beyond the Hitchcock allusions, including a disillusioned individual inadvertently entangled with a murder case, the film is indebted to Akira Kurosawa’s Rashomon, which uses a similar dramatic device that centers the narrative around the differing perspectives of the assassination from various characters.

De Palma, more than any of his contemporaries, understands the filmmaker’s role as a manipulator, and this device allows him to flourish this concept. Observing each perspective of the assassination is fresh and fascinating, leaving the viewer uncertain of the truth. For just a trashy thriller on the exterior, it is daunting how far De Palma goes to assert his athletic filmmaking prowess, with the crowning achievement being an unbroken take of Cage walking through the casino floor. The camera does things that shouldn’t be possible for a camera to execute, but De Palma strives to operate it ingeniously with every film. No shot is left boring. While Snake Eyes is purely a stylistic narrative, it does feature commentary on the artifice in film. It is quite self-aware of its trickery, and yet De Palma never fails to play his audience like a fiddle.

3. Play Misty for Me (1971)

1971 was a noteworthy year for Clint Eastwood. He portrayed the iconic Harry Callahan on screen for the first time, and made his assured directorial debut, to the likes of which are not expected for actors. Under the guidance of his mentor and Dirty Harry director, Don Siegel, Eastwood split duties as the star and filmmaker of Play Misty for Me. In surprising fashion, he did not begin his illustrious directing career with a western or cop film, but instead, pivoted into the direction of a psychological thriller. The genre was suited to display Eastwood’s chop behind the camera.

The film centers around a popular radio disc jockey, Dave (Eastwood), and the obsessive fan, Evelyn (Jessica Walter), who sends his life into a free fall. Viewers are never fully informed as to how or why Evelyn is drawn to Dave to an unhealthy degree, but this sentiment resonates with the power of Eastwood’s charm. While having one’s debut film be relating to fame and prominence seems quite vain, Eastwood has a graceful touch in examining himself and his stardom and has practiced doing so for the next 50 years. As a thriller, Play Misty for Me checks all the right boxes that are expected and coveted–to the point that Eastwood perhaps relies too heavily on genre formalities.

Additionally, the film lacks the meditative quality that would be the driving force of his future films. Eastwood leaves compelling character work on the table. The genre elements are effective enough to elevate a broad script, and the director has an eye for sharp imagery that complements the sleazy nature of the story. It was a bold move for Eastwood to delve into a thriller engaging with provocative sentiments, as Play Misty for Me preceded future landmark erotic thrillers such as Fatal Attraction and Basic Instinct. From the start, Eastwood showed his abilities as a filmmaking chameleon.

4. Three Days of the Condor (1975)

In response to the political turmoil at the time, paranoid conspiracy thrillers were a mainstay in the 1970s. No entity was more sinister than the domestic government. A year before All the President’s Men, Robert Redford starred in one of the most entertaining political thrillers of the time. With his frequent collaborator Sydney Pollack directing, Three Days of the Condor showed that downbeat thrillers about life or death in the face of superior powers were elevated popcorn entertainment in the ‘70s.

In the film, a Manhattan CIA researcher, Turner’s (Redford), co-workers are killed and are forced to evade the assassins out to get him as he discovers the truth behind this conspiracy. More populous and less weighty and the political thrillers of Alan Pakula, Three Days of the Condor works on impressive spectacle. Pollack’s directing of energetic chase sequences and suspenseful standoffs is stellar. As a film set in New York in the ‘70s, the film has an aesthetic edge over the competition. The screen presence of Redford and Faye Dunaway grabs the attention of the audience, even if they are unclear of the exact machinations of the plot.

In many ways, the film is a melting pot of collected thematic devices of ‘70s American cinema. Sometimes, Pollack tries to tackle everything without the proper sophistication. Certain plots, especially regarding the overarching plot of the Max Von Sydow character, are left better when not explicitly stated. It does not say as much about America as the film thinks it does. Either way, Three Days of the Condor is a worthwhile text due to its craft and precise tone. This is the perfect middle-brow film that mainstream audiences crave today.

5. Sorcerer (1977)

William Friedkin was one of the hot directors of the 1970s, cementing himself as an auteur with The French Connection and The Exorcist. His relentless kinetic energy behind the screen and innovative and daring visual language made him an automatic point of interest in the film community. For his follow-up to his smash-hit horror sensation, Friedkin went big with his rendition of The Wages of Fear. By going big, it meant that Sorcerer would feature one of the most disastrous behind-the-scenes film productions of all time–to the point of recklessness. Overlooked at the time, the 1977 film stands as one of the most impressive feats of filmmaking and thrilling cinematic joyrides ever.

Sorcerer tracks four separate criminals on the run from the law who conjoin in a small South American town and are offered $10,000 and legal citizenship if they transport a shipment of dangerously unstable nitroglycerin to an oil well 200 miles away. Friedkin maintains a thrilling momentum to the narrative even when the action and dramatic tension stall. The run-and-gun, handheld cinematography made famous from The French Connection is alive and well in this film. As the show-stopping driving sequences demonstrate, there is a level of slickness that prevents the filmmaking from being amateurish. Although viewers are purposefully restricted from learning much about the four main characters, Friedkin brings enough pathos to them that makes the already weighty stakes of the story feel overwhelming.

As a thriller, the genre does not excel much further than Sorcerer. A nihilistic decay of humanity preys upon the characters as they hold on for dear life in a run-down truck in the hope that the supply of nitroglycerin doesn’t eviscerate them. The prospect of money and citizenship tempts them with salvation, but the trucks used for transportation are merely a vehicle for their death.