In one of her last essays for the New Yorker, Pauline Kael turned the criticism inward. She celebrated and lamented having had to write in the pre-rental era, which meant that each “Current Cinema” column responded in real time to a film she had just seen, or it recalled films that remained stuck in the irritated corners of her memory. This, she suggested, lent her writing a sense of “urgency” and “excitement,” but also manifested her greatest flaw: “reckless excess, in both praise and damnation… I often got carried away by words. I’d run on, and I’d hit too many high notes.”

Maybe she underestimated how reckless flourishes and run-ons comprised so much of what readers loved about her writing. It’s what differentiated Kael from the other eminent critics of her time, particularly from Roger Ebert, whose measured, close-knit syntax seemed always to boil a film down to its essential components, leaving little room for embellishment. There’s a reason Kael never slapped a grade on a film. The point of reading her work wasn’t the recommendation, it was the intoxication of conversing with her as she worked through her feelings on the films that challenged her.

Kael seemed to have a special relationship with genre films that rose above lazy B-movie billings. Aside from musicals, thrillers often seemed the most direct way to her heart, and her incisive criticism helped to elevate their status in the public consciousness. She was an early champion for famous young filmmakers like Martin Scorsese and Brian De Palma, helping films like Means Streets and Carrie to find mass audiences. She demanded the most of these directors, and so long as their sets were well lit, she had a steel stomach for their goriest tendencies. Over twenty years since her death, her taste in crime thrillers remains fresh, and her writing, as ever, is worthy of rereading.

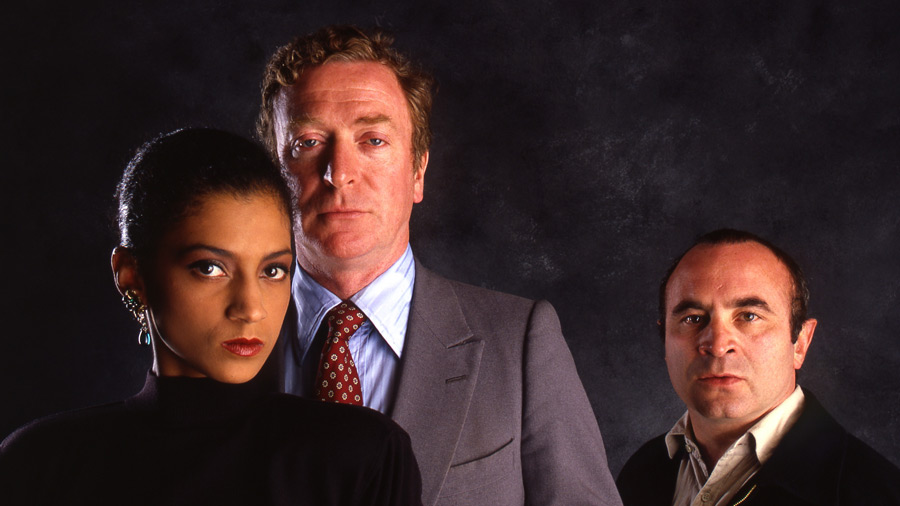

10. Mona Lisa (1986, Neil Jordan)

Pauline Kael “succumbed” to this film, which is to say that she knew better than to really take its bait but couldn’t restrain her indulgent impulses for long. Despite its considerable acclaim (including a spot on BFI’s “Top 100 British Films of the 20th Century” list), Neil Jordan’s noir thriller Mona Lisa provoked dissonant reactions from some of the 1980s’ most influential critics. At one end of the spectrum was Ebert, who awarded the film with his coveted four-star badge, lauding in particular the atmosphere and the masterful performances from stars Bob Hoskins, Cathy Tyson, and Michael Caine. At the other was Vincent Canby of the New York Times, who dismissed the project as “less a true noir film than a comment on one,” arguing that the overly referential script was “as bloodless as an abstract theory.” It was Kael, though, who had her finger on the pulse of this film. How much one enjoys it might be a factor of one’s willingness to submit to thoroughly constructed “kitsch” (as Canby puts it) for the sake of great lighting and some truly dynamic acting.

With her unique brand of heartfelt acidity, Kael crooned that the film “reeks of intellectualized noirishness”—a writer and director overworking the best of decent material. It’s the actors that enliven the story for her. She’s particularly bullish on the unlikely chemistry of George (Hoskins), an aging Cockney criminal with the sentimental spunk of a Jack Russell terrier, and Simone (Tyson), an upper crust sex worker trying to save her friend from a vicious pimp. They collide when George, owed a favor after serving seven years in prison to protect Lord Mortwell (Caine), is given recompense through a chauffeur job. Mortwell tasks him with bringing Simone from client to client.

As their friendship develops, George’s desire to help Simone (and his desire for Simone) bring them deep into a blackmail scheme predictably run by the truly despicable Mortwell. Even if she had no tolerance for kitsch (and she did have some), Kael would have recommended the film simply for the sake of Michael Caine’s malevolent performance. “I can’t recall a screen star of Michael Caine’s rank,” she praised, “who has had the talent and the willingness to play a man so foul and repugnant.” For acting like that, even Kael succumbs.

9. Dressed to Kill (1980, Brian De Palma)

It’s tempting to wonder what Kael would say about De Palma’s thirteenth feature now, over forty years since its theatrical release. Dressed to Kill is a richly layered thriller with a garish sexual politics that would never be greenlit in 2023. Overtly worshipping and satirizing Hitchcock’s Psycho, Dressed to Kill aligns gender dysphoria with psychopathic violence, a long-standing trope reified repeatedly throughout film history.

At the time, none of this mattered to Pauline Kael, whose standing within queer communities was often tenuous anyway. She spent hundreds of words extolling the famous art gallery scene, the smooth introduction of the split diopter (which quickly became a key component of De Palma’s myth), and the performances of Michael Caine, Nancy Allen, Keith Gordon, and Kate Miller. But ultimately, her review is an enshrinement of De Palma himself, whom she admired as much as any American director in her lifetime. She felt that Dressed to Kill signified the arrival of a fully actualized De Palma, an auteur finally in complete control of the narrative and technical tools available to realize his vision.

8. Eyes of Laura Mars (1978, Irvin Kershner)

Kael wrote about Laura Mars in one of her most famous essays on Americans’ post-Vietnam fear of violence in movies. She analyzed the public’s squeamishness around blood and the vulnerability of the body, particularly of the eyes, positing that slitting a throat does not evoke the moralizing horror in audiences so fervently as an attack on the eye. As its moniker suggests, this film is all about eyes, and Kershner’s camera—the only untarnished eye in the film—keeps its gaze locked on everyone else’s.

The original poster is an image of Faye Dunaway’s face darkened nearly to the point of obscurity, with only her eyes bleached so severely that they radiate demonically upon the viewer. The audience is asked again and again to consider its own vision, to question what it means to gaze upon other bodies, upon violence, and upon the things it finds beautiful.

Dunaway’s titular character is a fashion photographer famous for her sexy, gory, and controversial images that sell widely. She also happens to telepathically inhabit the eyes of a murderous maniac as he stalks and kills (by stabbing them in the eye, of course) the people in her artistic circle. The telepathy is completely outside of her control. The visions become more frequent as the killer closes in on her and her closest friends, slowly driving her toward paranoia and isolation. Desperate, she turns to straight-shooting police lieutenant John Neville (Tommy Lee Jones) to help her find the killer. Their ensuing romance both comforts and complicates, culminating in a (highly predictable) twist.

Above all, Kael loved the pace and the performances, as well as the feel of “subterranean sexiness.” She felt that both Dunaway and Jones were perfectly cast: Dunaway because she was “glamorously beat out—just right to be telepathic about killings,” and Jones because of his “cat burglar’s grace, his sunken eyes, rough skin, and jagged lower teeth that suggest a serpent about to snap.” She delights in their chemistry, noting that they are among the most unlikely, yet somehow believable lovers she can recall. And despite being lukewarm on John Carpenter’s script, she ultimately puts the film into conversation with classics like Rosemary’s Baby for its ability to render “justifiable female paranoia” on screen.

7. Pixote (1980, Héctor Babenco)

Labelling Pixote a crime thriller is misleading, although there’s no shortage of crime or shocking (if not thrilling) moments. Héctor Babenco’s hyperreal exploration of poverty, masculinity, queerness, and carcereality in urban Brazil is a brilliant but utterly brutal two hours. This is a film to watch with a blanket and a strong beverage. Prepare to be gutted.

Seen through the eyes of ten year old Pixote (Fernando Ramos da Silva), Babenco takes viewers on a tour of Sao Paolo’s underground for lost boys and trans girls. According to Martin Scorsese (who loves this film), Babenco first attempted to tell this story in documentary form but had to adjust to fiction when a reformatory suddenly stopped cooperating. The film quickly achieved international acclaim, thrusting the Argentinian director into the throes of Hollywood, where he would make prestige movies like Kiss of the Spider Woman and Ironweed.

For her part, Kael was genuinely moved by Pixote, even if she didn’t think it quite raised to the level of a masterpiece. She admired Babenco’s style, spending paragraphs celebrating his atmospheric lighting and the improvisational feel of his images. “The incidents don’t appear to be set up for the camera,” she said, “things just seem to be happening and every image is expressive.” She went on to praise the performances of Jorge Julião as Lilica, a trans girl who partners with and looks out for Pixote, and Marília Pera as Sueli, an eccentric sex worker who plays a key role in the second half of the film. However, while most critics (most notably Vincent Canby) praised da Silva’s acting in the lead role, Kael was less convinced, wondering if the consistently blank stare on his face was more a factor of inexperience than of character.

Any contemporary viewing of Pixote is made all the more devastating by the tragic death of its young star less than a decade after the film’s release. Following the films release, Fernando Ramos da Silva, who came from a background akin to his character’s, was offered roles in prominent Brazilian television shows. Nothing stuck. Scorsese suggests that the teenager was illiterate, which made it difficult for him to memorize lines. After numerous firings, da Silva returned to life on the impoverished margins of Sao Paolo, where he was ultimately killed in a police raid at the age of nineteen. Watching sunset on a Rio beach, Pixote’s friend Lilica sings to him, “The sun still shines on the road I never travelled,” and it hits with a tender, feverish despair.

6. Thieves Like Us (1974, Robert Altman)

Just before she died in 2001, Pauline Kael famously laid bare her feelings about Robert Altman’s peculiar career: “I don’t know how to account for the fact that when he’s good, he’s superb, and when he isn’t good, he’s nothing.” Yet, if she wanted the answer, she needed only to read her own writing from twenty-five years prior. Given her encyclopedic knowledge of American and European film history, perhaps the biggest compliment that Kael could dole out to any director was that they surprised her. Very few filmmakers accomplished this once, let alone repeatedly, but Altman was one of them, and Thieves Like Us, the auteur’s 1974 bank heist thriller, seemed to illuminate to her what made this possible.

“When an artist works right on the edge of his unconscious, like Altman, not asking himself why he’s doing but trusting to instinct (which in Altman’s case is the same as taste), a movie is a special kind of gamble. If Altman fails, his picture won’t have the usual mechanical story elements to carry it, or the impersonal excitement of a standard film. And if he succeeds aesthetically, audiences still may not respond, because the light prodigal way in which he succeeds is alien to them.”

Maybe what seemed alien to Kael about this particular film was that she considered it “the closest to flawless of Altman’s films.” She didn’t like it as much as McCabe & Mrs. Miller, Nashville, or even The Long Goodbye, but she felt that Thieves Like Us was Altman’s most fully conceived work to date. His clear vision, coupled with star making performances from Keith Carradine and Shelly Duvall (who she said “melts indifference” and makes one “unable to repress your response”), made Kael believe that this film would reach audiences in a way that even his previous successes hadn’t. She felt that it would be almost universally beloved, or at the very least, that one would have to “fight hard to resist it.” But for whatever reason, this prediction did not quite stand the test of time.

The heist thriller set in the ‘30s is among the least seen of Altman’s critical successes. It did minimal business at the box office (especially compared to the success of Nashville just one year later), received no awards buzz, and is impossible to find on any streaming service. However, if one does get their hands on an analog copy, Kael would suggest sitting back and enjoying a legendary director at the peak of his powers.