6. Glengarry Glen Ross (1992)

Al Pacino is a renowned actor on the stage. A winner of two Tony Awards, his vibrant vocal range and resound manner of speech are perfect for theater productions. When David Mamet brought his play, Glengarry Glen Ross, to the screen, no one should have been surprised that Pacino would chew up the scenery and exploit the magnetic energy of every line of dialogue. This is one of his best performances, which was rightfully Oscar-nominated, but was overshadowed by his long-awaited win for Best Actor for Scent of a Woman.

Glengarry Glen Ross focuses on overworked and stressed real estate agents fighting to keep their jobs amid the pressure cooker of securing leads and closing deals with clients. Make no mistake, some of the quickest, sharpest, and brightest lines of dialogue, and most soulful soliloquies can be found in this film, directed understatedly, yet superbly, by James Foley. Mamet’s writing is a character on its own–operating on a similar wavelength between each character, but disparate enough to make each real estate agent three-dimensional and internally broken. Foley’s quiet visual aesthetic of the smoky interiors and rainy exteriors evokes a sinister noir element lingering over the drama in Glengarry Glen Ross.

Pacino plays Ricky Roma, the most respected and accomplished salesman of the group. The actor carefully conveys a suave arrogance to his character. He seems removed from the panicked angst of the rest of the sales force, but it isn’t until the threat of losing out on a valuable deal that he unravels into a tornado of unhinged wrath. Overall, the actor is cohesive with his impressive slate of co-stars, which includes Jack Lemmon, Ed Harris, and the late Alan Arkin. The wild Pacino that audiences grew to love is in full force, but thanks to Mamet’s script, ‘90s Pacino was never as alluring as he is in Glengarry Glen Ross.

7. Carlito’s Way (1993)

On paper, Al Pacino’s 1993 reunion with director Brian De Palma seemed like a retread. Because Carlito’s Way features Pacino playing a Latin gangster in a slick and pulpy crime drama, people were ready to write this off, especially since Scarface had not yet fully announced itself as a cult classic. However, the film is unexpectedly romantic, reflective, and a revisionist text of the gangster genre. The genre trash that De Palma excels in slowly pulls the rug out from viewers and creates a heartbreaking tragedy.

In Carlito’s Way, released convict Carlito Brigante (Pacino) pledges to reform himself from the drug trade by owning a nightclub, as surrounding forces pressure him to engage in criminal activity. De Palma’s meticulous pacing, aided by his expressive camera movements, allows the film to be meditative of a life of crime and a figure desperately attempting to reform himself. Never seeing a set piece that he couldn’t exploit for dramatic and thrilling story beats, various settings in Carlito’s Way, such as the nightclub and climatic subway station chase, are incredibly operatic.

All the characters are unassuming, even at the most deplorable, seen in the shady attorney, David Kleinfeld (Sean Penn), or at the most innocent, seen in Carlito’s romantic interest, Gail (Penelope Ann Miller). Every choice that Carlito makes is consequential to the audience’s understanding of his plight and his fate, but De Palma forces viewers to interpret the film’s universe on their own. Pacino’s performance bodes well with the star’s screen persona. Carlito is consistently on the verge of bursting out in typical Pacino style, but his dedication to reform causes him to maintain a steady head. Carlito’s Way shows Pacino at his most vulnerable–oblivious of his inevitable demise but steadfast in reformation.

8. Donnie Brasco (1997)

The presence of an acting giant like Al Pacino is essential to elevating material. In the case of Donnie Brasco, this film was destined to be disposable with the likes of many mob-related films attempting to reach the heights of Martin Scorsese. Thanks to Pacino’s pairing with Johnny Depp, the film offered something more thought-provoking than its counterparts.

Based upon a true story of FBI agent Joseph Pistone’s undercover infiltration of the mafia, Donnie Brasco primarily focuses on the relationship of Pistone (Depp) under the titular alias, and aging mobster Lefty Ruggiero (Pacino), who fears he is facing his last days. Director Mike Newell follows the script and source material in a rudimentary fashion. While it moves swiftly, the film deserves an active visual style and a sense of formalism. Thankfully, Donnie Brasco is engaging, keeping viewers locked on to the story through every narrative component.

From their first interaction, the chemistry between Depp and Pacino is electric. They play off each other in their strengths and weaknesses as characters, with the shifting power dynamic in their standing in the mob clouding over them. Pacino’s role as an experienced mobster is beneficially not what most audiences envisioned. More often than not, Lefty is powerless and finds soothing comfort in his loving marriage and earnest friendship with Donnie, who, tragically on his part, isn’t who he claims to be. For as much as he is celebrated for his craft and screen iconography, Pacino’s abilities as a nuanced, soulful performer are undersold. Through his eyes alone, he can carry any undercooked pathos and dramatic tension.

9. Any Given Sunday (1999)

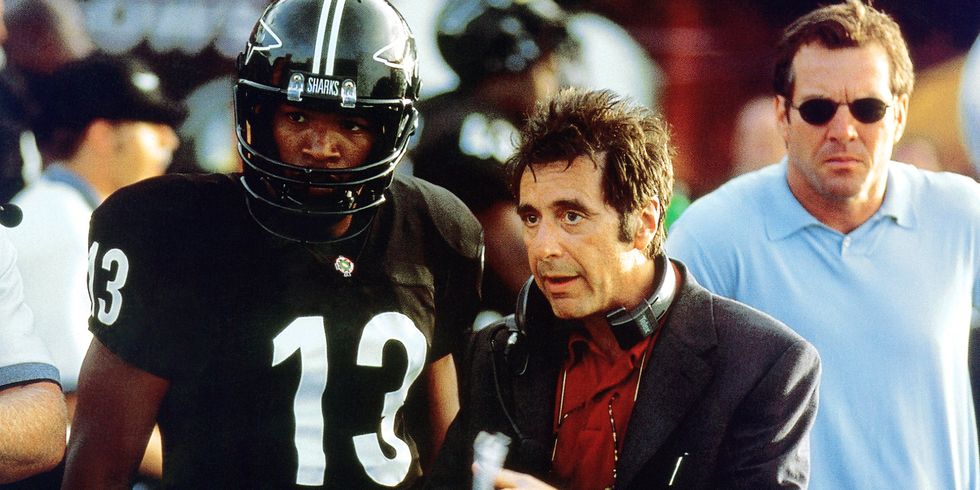

When the director of Vietnam War takedowns and panicked conspiracy thrillers in Oliver Stone decided to put his spin on professional football, anything less than an unhinged viewing experience would have been a letdown. Any Given Sunday is the kind of film where its glaring imperfections are as fascinating and entertaining as its strengths. At the center of Stone’s maniacal 1999 film, representing both the pros and cons, is Al Pacino.

Any Given Sunday follows a season-long odyssey of the Miami Sharks, the professional football squad led by head coach Tony D’Amato (Pacino), who combats ownership and a band of ego-driven stars and up-and-comers, including quarterback Willie Beaman (Jamie Foxx). The film shifts between a broad scope of the NFL’s (the league refused to be affiliated with the film) capitalist urge and compromise of player safety, a syrupy romanticism of the sport, and a closer examination of a relationship between an aging coach and a rookie. No matter what perspective Stone is tackling, Any Given Sunday leans into absurdity. Game sequences are depicted with the volatility of a war battlefield.

With seemingly no self-awareness, the film employs shock value when attempting to criticize football’s barbaric methods of treating its players. For as over-the-top and ham-fisted as his performance is throughout, there is no denying the resonance of Pacino’s performance. He is believable as a seasoned and fiery head coach. This is especially realized during his spellbinding delivery of the iconic “inches” locker room speech. Juxtaposed to his dynamic persona as a coach, Pacino eloquently conveys a man who is broken and lost without football. Stone’s often overwrought earnestness and maximalism regarding the sport is perfectly dialed into the actor’s repertoire.

10. Insomnia (2002)

Early in his career, before amounting to one of the premiere blockbuster visionaries working today, Christopher Nolan excelled in crafting twisted neo-noirs. In an alternate universe, he would have continued to make films like Memento and his overlooked 2002 film, Insomnia. The film is a riveting late-period stage for Al Pacino. While being put through the wringer of Nolan’s subversion and formalism, Pacino explored the deepest roots of his psychological angst.

Insomnia, a remake of a Norwegian film of the same name, follows the story of a sleep-deprived detective, Will Dormer (Pacino), who is dispatched to a small town in Alaska where the sun never sets while investigating the murder of a local teen. Nolan’s direction complements the dreary environment of the gloomy setting. There is always something sinister lurking on the screen and with the psychological balance of the characters. If anything, Nolan plays into the hallucinogenic aspect of the story too frequently.

The director is often criticized for his lack of genuine emotional cohesiveness, and this manifests itself in Insomnia, with Nolan pushing for psychological thrills without practically conveying such feelings. Nonetheless, his manipulation of genre and narrative beats are impressive, and his knack for leaving audiences on the edge of their seat is profound.

Pacino effectively portrays the angst of someone deprived of sleep and running into dead ends throughout his investigation. Insomnia likens Pacino to some of his quieter roles in the early ‘70s. The performance is broad in spurts, but the actor’s natural ability to reach the most complex emotions is unparalleled. Even when Nolan’s direction is redundant, Pacino keeps the Hitchcockian themes and stakes thoroughly engaging.