The Western is one of the most formative genres in the canon of cinema. The American Frontier is the ideal setting for a film that examines the past, the present, and the future.

Through its location, characters, and concepts, Westerns, in gracious and scathing fashions, dissects American history and culture. While an archaic genre today, Westerns were run-of-the-mill in the greater history of Hollywood, leading to countless underrated gems in the field throughout Hollywood history.

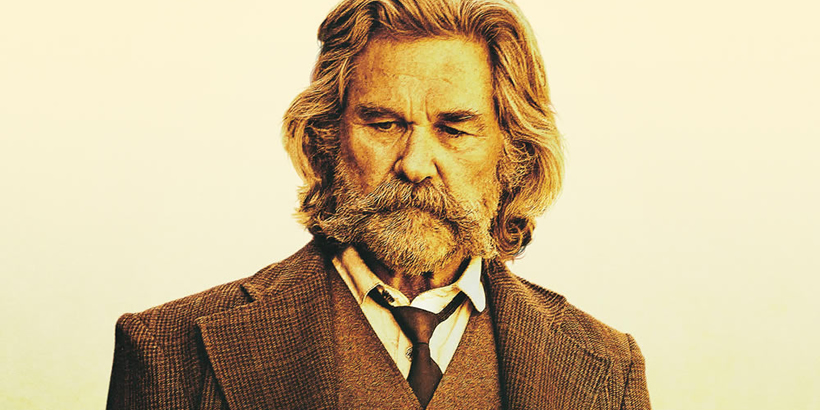

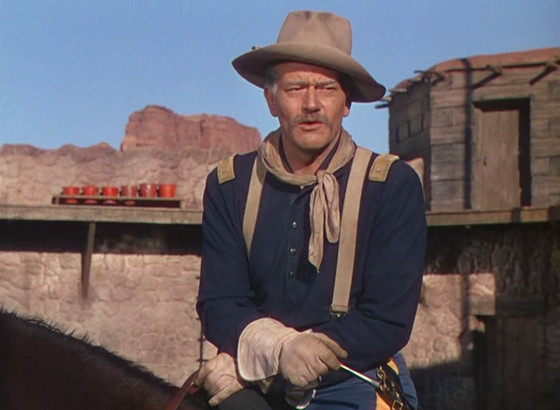

1. She Wore a Yellow Ribbon (1949)

When it comes to Westerns, John Ford is the embodiment of the collective iconography of the genre and how the public interprets its films. Perhaps the greatest American director in history, the history of the nation, Western mythology, and the plight of America as a whole can be consumed through the vast and poetic filmography of Ford. His most underrated Western, She Wore a Yellow Ribbon, shows the director at his most vibrant, painterly, and majestic.

In the second film in Ford’s spiritual Cavalry trilogy, Captain Nathan Brittles (John Wayne), on the eve of retirement, commands one last patrol to prevent an impending Native American attack on a village while he and his crew are enchanted by Olivia Dandridge (Joanne Dru), the niece of the commanding officer who must be evacuated. Never has the old West been captured on film with such beauty and romanticism as in She Wore a Yellow Ribbon. Every image that Ford paints through Technicolor is a riveting tale on its own, through in the most maximalist ways through vistas or the more subtle fashions, such as how Wayne is positioned with the horizon or how the spiritualism of Dandridge through her ambiguous titular ribbon.

While, through a contemporary lens, the film’s politics are disreputable, Ford’s overwhelming graciousness and poetry with his characters and the cavalry’s role in the development of the New Frontier is too magnetic to dismiss. While She Wore a Yellow Ribbon is not revisionist at heart, especially when compared to Ford’s future pictures, there is an unmistakable pathos. The Captain reckons with the value of combat, the battalion is war-torn and emotionally fragile, and the juxtaposition of gorgeous painterly vistas with the doubts and trepidations of the mission fully realizes Ford’s vision. She Wore a Yellow Ribbon’s blend of melancholy and fleeting patriotism represents Ford at his most sentimental.

2. Ride Lonesome (1959)

Despite being severely overlooked by mainstream audiences, Budd Boetticher is certainly one of the premiere voices of Western filmmaking. His imagery of the Old West is indebted to its classic iconography and a groundbreaking postmodern vision that was ahead of its time. The director’s finest achievement, Ride Lonesome, is a lean, propulsive, powerful Western that endlessly entertains and provokes audience sensibilities.

In Ride Lonesome, a bounty hunter, Ben Brigade (Randolph Scott), captures a murderer, Billy John (James Best), and enlists the help of two outlaws to protect themselves against an onslaught of attacks from Native American tribes, only to have the outlaw’s brother (Lee Van Cleef) right on the bounty hunter’s tail. The narrative rigidly follows a refreshing point-A-to-point-B structure. While Boetticher is invested in the machinations of Western folklore and the history of combat and crime in this environment, he is never distracted by the inherent visceral narrative at hand.

Regardless of the brief runtime, Ride Lonesome is supported by brisk, economical storytelling that operates cohesively while simultaneously accepting the audience as well-informed and sophisticated viewers, especially concerning Western ideology. Boetticher embraces the genre aspects of Westerns as passionately, if not more, than any of the directing icons in this field. His film puts the notion that tropes and genre norms are detrimental to rest. Western tropes become familiar for a reason–it’s because they allow for compelling filmmaking and rich characterization.

Altogether, the film constantly bursts off the screen with every shoot-out and Western vista. Ride Lonesome, in a similar spirit to Leone, is an engrossing convergence of the imaginative Western with the exuberance of the most satisfying B-movies.

3. Duck, You Sucker! (1971)

Even with such a limited filmography, Sergio Leone’s impact on the Western genre is historic. His elevation of the Spaghetti Western matched the American painterly and poetic realization of the New Frontier. In Leone’s case, despite his sophistication, he was not afraid to make the genre grimy, and in turn, demystify Western iconography most aggressively. This is most evident with his post-Dollars trilogy gem, Duck, You Sucker!

Leone’s Western centers around a bandit, Juan Miranda (Rod Steiger), and an I.R.A. explosives expert, John H. Mallory (James Coburn), who teams up to rebel against the government and lead a Mexican revolution. Duck, You Sucker is a dynamic blend of low-brow and high-brow sentiments.

From the title alone, the film relishes pulpy visual language and dialogue. Steiger and Coburn are quite theatrical in their performance but are undeniably captivating, supported by Leone’s sense of black comedy. It appears as though the historical and political backdrop is unwarranted in this depiction of two disgraced individuals. However, Leone’s epic scope that he cemented with The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly and Once Upon a Time in the West is carried over in his 1971 film.

In typical fashion for the director, the “heroes” of Duck, You Sucker are notably unglamorous. They hardly stray from their roots as bandits. Most of their benevolent deeds are manifested by accident and fortunate circumstances. Leone’s revisionism is in full force, signaling that the triumphant moments in the fight for liberty are supported by the efforts of unsatisfactory rebels who conflict with each other. Duck, You Sucker examines violence with consequential and justified stakes, but still ponders the dignity of the matters overall.

4. Jeremiah Johnson (1972)

Throughout his impressive career, Robert Redford refused to coast on the laurels of his movie stardom and status as a matinee idol. He was sophisticated and curious about exploring various facets of genre and American history. Amid a fruitful collaboration with Sydney Pollack, Redford cemented himself into Western iconography in Jeremiah Johnson, a subversive New Hollywood take on the genre and his stardom.

In the film, Redford plays the titular role of a mountain man who vows to live the life of a hermit, and unwillingly becomes a target of vendetta by a Native American tribe. The actor is convincing as an alienated outcast in a post-Mexican War environment attempting to discover something more profound in life. What enriches Jeremiah Johnson is the film’s comfort with ambiguity. It is ultimately unclear why Johnson seeks out this plight, but Redford’s weighty performance is all the audience needs to follow this harrowing journey into the snowy mountains, the film’s stand-in for the old West. The majestic aurora compels viewers to be in awe of this world and Johnson’s reckless adventure. If anything, the dissection of Western text is left slightly undercooked in the film.

The film is passive in its engagement with the character as a false Western hero in his bouts with the local tribe and protection of an abandoned mother and her young son. The character’s pathos is infused with that bleak, ‘70s lingering doubt and cynicism. Without any forced characterization, the decay of the American spirit and desperate retreat to an idealistic American forefront is conveyed through Pollack’s immersive direction. However, Jeremiah Johnson skews from the tired angst of “we live in a society” sentiments, as Pollack is a naturalist at heart.

5. Bronco Billy (1980)

For cinephiles, there is no comfort and standard of excellence quite like Clint Eastwood in the Western genre. His iconography of the outlaw matches John Wayne’s embodiment of the sturdy lawman. However, as both an actor and director, he strived to push the envelope on revisionist perspectives of the genre–even more so than John Ford. In one of his more minor outputs, Bronco Billy shows Eastwood as a cowboy figure in an unprecedented setting, but ideal for the star and director’s sensibilities.

Bronco Billy centers around the titular modern-day cowboy (Eastwood) struggling to keep his Wild West show afloat during hardship. Despite his image as the quintessential masculine icon, Eastwood has always been interested in entertainers in show business, as seen in his films Honkytonk Man and Bird. This effectively balances the artifice of the Western backdrop through literal artistry.

Combining this fascination with the Western backdrop creates a film that unconventionally demystifies the genre’s lore–a phenomenon that cemented Eastwood’s legacy. When Billy develops a relationship with Antoinette (Sondra Locke), she realizes that these figures in the circus are not as idealist as the Western folklore they represent. The traveling show is outdated and deeply unromantic.

Throughout Bronco Billy, the modernized West mirrors a vision of the frontier that is compromised by a distorted vision of its creators. The Antoinette character, a typical damsel in Westerns, is most affected by the group’s inflated mystification. The characters reckon with themselves rather than an enemy force. Bronco Billy evokes the pathos further realized in Eastwood’s finest films—the kind that soberingly reflects on the decay of the West from the eye of the beholder.