3. Argo (2012)

Just years prior, Ben Affleck was seemingly at rock bottom. In a flash, he was reincarnated as the director of the Best Picture winner. A reinvigorated star and established director, Affleck once again saw himself employing a familiar yet forgotten film genre back into the mainstay with his same brand of effective middle-brow entertainment. What seemed to be just a riff on a ‘70s political thriller, loosely inspired by the work of Alan Pakula, with glaring factual liberties, Argo caught the eye of Academy voters in 2012. If there was ever a master filmmaker of TNT programming on a Sunday afternoon, Affleck would be running away with the crown.

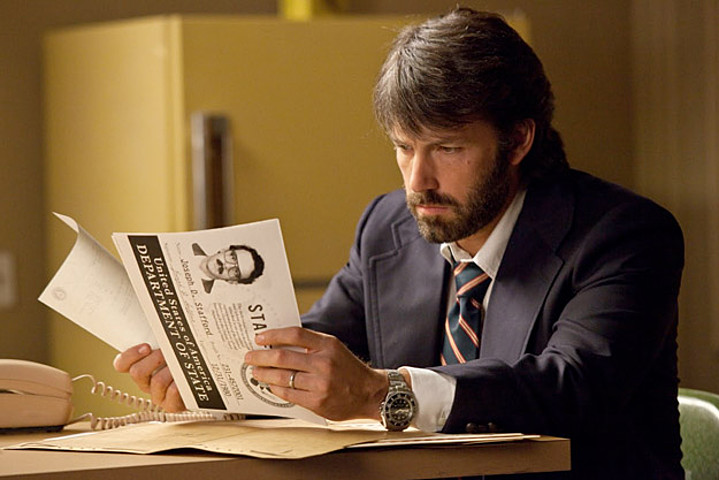

Based on a true story set against the backdrop of the Iranian hostage crisis in 1979-1980, Argo follows the CIA’s plan to rescue six Americans in Tehran, coordinated by Tony Mendez (Affleck) and acting under the cover of a Hollywood producer scouting for locations for a science fiction film. The intersection of art and American history made this film quite favorable to Oscar voters, but Affleck’s genre sensibilities hide any thread of Oscar bait when watching. Affleck, who shockingly was denied a Best Director nomination, demonstrates some of his most refined filmmaking to date by balancing his preference to close, documentary-like photography with the global stakes of the hostage crisis.

Like most of the director’s work, Argo is immaculately paced–maintaining a lingering intensity throughout the runtime, whether the setting is inside the CIA’s office, downtown Tehran, or the confines of the hostages. The consistent energy of the film is on the heels of an impressive ensemble cast all giving sturdy performances, from Bryan Cranston, John Goodman, Victor Garber, Tate Donovan, and an Oscar-nominated Alan Arkin.

While the film stands as a modern spin on the ‘70s political thriller, it does so more in appearance than following through thematically. While narrative films hold no responsibility to represent 100% factual correctness, Argo pushes the limits of Hollywood liberties–to the point that it makes the film too simple and clean for its own good. Also in line with Affleck’s filmography, the film leaves interesting and thought-provoking commentary on the table. The times that it configures itself for crowd-pleasing entertainment could be used to dissect the machinations of government agencies or engage with the complicated relationship that the American public has with covert bureaucracies.

Between his allegiances with the CIA here and with Nike in Air, Affleck ought to consider creating borderline propaganda for the common folk one of these days. Having said that, if anyone was going to bastardize a real-life foreign affairs issue by inaccurately centering around the CIA, Affleck is the director to make it a worthwhile watch that is undeniably entertaining.

2. The Town (2010)

In his sophomore bid as director, Ben Affleck swung for the fences by ostensibly crafting his take on Michael Mann’s heist epic, Heat. In addition, he returned to the screen and remained there from there on out. Where Gone Baby Gone was fully indebted to his hometown of Boston stylistically, The Town is Boston flourished as a character, and it is utilized as a historical backdrop to the film’s characters and story. On a broader scale, the film is practically an homage to the heist genre, with its roots traced back to Mann’s work and films such as The Friends of Eddie Coyle.

Affleck’s crime saga follows an archetypical “one last job” narrative of a bank robber, Doug MacRay (Affleck), who attempts to reform his life and start over with his romantic partner, Claire Keesey (Rebecca Hall), a bank teller who was taken hostage during one of his heists. The Town is an all-encompassing story, as Affleck weaves in a traditional heist thriller, the criminal kinship of friends, a budding romance, a detective story, and how everything is a product of their environment. Even though the film depicts ruthless criminals, there is a sense of romanticism affected by Affleck’s love for the city. Doug and his partner in crime, Gem Coughlin (Jeremy Renner, in an Oscar-nominated performance), are in this business because it was passed down from their family.

The film expresses interest in how the sins of one’s fathers come to fruition for their offspring. The director’s Boston origins have become a personality trait of sorts with his stardom, and The Town is the true manifestation of his standing as a Boston celebrity, as his understanding of its societal roots drives the film’s narrative. The neighborhood of Charlestown is used as the backdrop of the characters’ motivations. Bank robbing is just a matter of life when one is raised in Charlestown. The North End and Fenway Park heists integrate the city effectively and naturally, and the precise direction of them could only be executed by a local native. The heists are the perfect demonstration of Affleck’s sturdy and seamless direction.

The Town is undoubtedly solid, but the captivating storytelling leaves the audience yearning for more. The structure of the film created the potential for a more in-depth narrative–one that digs deeper into the pathos of Doug, his familial bonds through crime, and repressive codes of masculinity. The film commonly strives for middle-brow beats when the ambitions of a Michael Mann film are waiting to be exploited.

On the flip side, the compounding interests of flashy blockbusters and meditative character drama benefit the film’s entertainment value. While it generally favors the former, one could analyze the film in relation to its examination of a working-class neighborhood brought up on crime. Not necessarily a bonafide classic, The Town will still remain a timeless film that is easy to watch and satisfies the most fundamental elements of solid filmmaking to the fullest.

1. Gone Baby Gone (2007)

The pinnacle of Ben Affleck’s ability as a director came in his first shot, as well as the only time he’s stayed exclusively behind the camera. In 2007, the last thing moviegoing audiences were expecting was for the star, who was coming off a string of flops and ridicule in tabloids, to take a seat in the director’s chair. People may have laughed at the idea, but it turned out that Affleck had some storytelling chops. Gone Baby Gone announced him as a real filmmaker with a clear voice behind the camera–one who could integrate a familiar concept and put a modern spin on the genre.

Based on a novel by Dennis Lehane, Gone Baby Gone follows a pair of private detectives, Patrick and Angie (Casey Affleck and Michelle Monaghan) investigating the kidnapping of a little girl, causing professional and personal turmoil for all parties involved. The film is indebted to the beats and murky undertones of detective stories and classic film noir, as the story unravels into a darker rabbit hole with each unfortunate discovery surrounding the case. Casey Affleck and Monaghan are stellar in their portrayal of investigators who are in over their heads, commonly being doubted for their young age. The batch of characters, including police detectives played by Ed Harris and John Ashton, and the mother of the missing girl, played by Amy Ryan in an Oscar-nominated performance, are all morally gray and refreshingly uncinematic in their lack of glamor.

Gone Baby Gone was the blueprint for the characterization of Boston employed in The Town. Throughout the narrative, Affleck is committed to displaying the most authentic portrait of his hometown. Every street and side character is true to life. He identified that Boston, due to its downbeat working-class environment, is the perfect setting for a detective noir. Like all great moody mystery films, the plot takes a back seat to the vibe in this film.

The script is superb, which Affleck co-wrote with Aaron Stockard. However, the visual language is uninspiring in certain instances, particularly in thrilling action sequences, and they serve as reminders that Affleck was a rookie director here. These moments feature no proper framing of the action at hand, as Affleck chooses to shoot things frantically to capture the intensity on screen. The repetitive use of close-up shots curtails much of the cinematic language that Affleck was striving for in the film. Especially since the setting is integral to the story, it would be nice if Affleck decided to zoom out every now and then.

Despite all this, Gone Baby Gone is an excellent picture. Even if the visual framing is amateurish in spurts, Affleck’s direction is assured throughout–evoking the sense of a passion project for the star-turned-director. The film signaled a comeback for Ben Affleck as a star and filmmaker. While he has yet to reach the same heights on his first try, audiences have grown to appreciate his contributions to cinema over the last 15 years.