5. Jules and Jim (François Truffaut, 1962)

Love can make people do stupid things. Sometimes those things can be absurdly dumb cause they do not know how to live without it, or they are too desperate for it. Such is the case for French New Wave classic Jules and Jim. Directed by new wave icon François Truffaut the story is about a love triangle between three friends: Jules (Oskar Werner), Jim (Henri Serre) and Catherine (Jeanne Moreau) and how they all bounce off one another in order to achieve love and happiness.

For as much trouble as one can expect to arise during a love triangle there is also a great deal of comic farce that takes place with how these three try to maintain some normalcy. The uniformity of the film is always in flux as Moreau’s character Catherine possesses incredible impulsivity and power over the two men that makes her as deadly as she is gorgeous. The nature of romance is interrogated through their actions and illustrates how people can be so desperate for love they will attach themselves to any kind of situation just so that they can experience it.

For a movie that centers on the ever-changing dynamic of this triangle it also deals with many of the negative consequences of choosing to love and the sacrifice that can come with it. There is no end goal that any of the three leads have in terms of what they want out of love, but they just want contact with it whenever possible and they suffer without it. Jules and Jim in equal measure put themselves in uncompromising situations by choosing to favor Catherine which puts their love for her to the test in ludicrously bizarre action that makes the romance all the more preposterous.

4. Close-Up (Abbas Kiarostami, 1990)

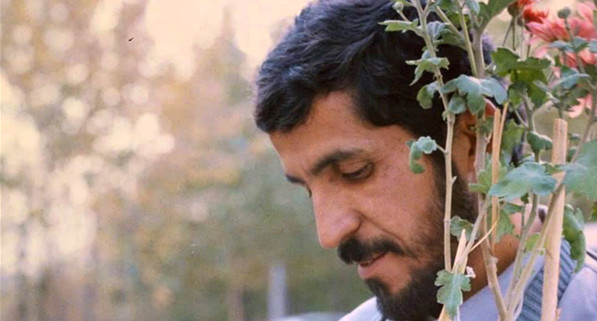

There are some real-life stories that are so crazy they demand to be examined in order to distinguish the facts from the fiction. But what if there was no such concern for truth and instead ideas are presented without comment or question about reality? Such is that conceit of Abbas Kiarostami’s docufiction masterpiece Close-Up. The film follows the true story of Hossain Sabzian, a film lover who impersonates his hero Mohsen Makhmalbaf in order to convince a family to star in his new film. The film follows the trial of Sabzian and as it unfolds the truth of what the viewer is watching begins to blur as it switches back and forth between verité style courtroom footage and compelling drama outside of it.

The notion of truth and identity are bended to the nth degree in this film as many (if not all) of the characters in the film are actors playing themselves in order to give the most realistic approach possible. The accounting of Sabzian’s crimes at first plays out like he is a classic conman looking to scam an unsuspecting family but there is a deep purpose and innocence that flows through Sabzian that calls into question the maliciousness of the crimes. It’s presented like any documentary footage would be presented but something is just a little off as the audience clues in to Sabzian’s motivations as well as many of the other characters.

What Close-Up does that differs from a standard documentary or biopic is that, as mentioned before, it is more concerned about introspection and identity than a true recounting of events. All the drama and process of the story is secondary as the film uses that as a backdrop to reflect on how art can move and shape people and how the principles of artistry can be under attack from those who aim to suppress it.

3. Mulholland Drive (David Lynch, 2001)

There has never been such a downbeat and destroying story about Hollywood than in David Lynch’s neo-noir thriller Mulholland Drive. The story centers on perky Hollywood hopeful Betty (Naomi Watts) who agrees to help a woman named “Rita” (Laura Harring) suffering from amnesia to get her memory back. Betty and Rita look for clues across the city of dreams to try and discover Rita’s identity, leading them to some dark places and confront them with horrifying truths.

The suspense of Mulholland Drive manifests itself in fantastical ways that exist on another plane of reality as opposed to rationally. The famous scene at Winky’s diner alone is enough nightmare fuel for a lifetime but what makes it such an ominous thriller is how disarming the film can be. Throughout Mulholland Drive the characters that the protagonists interact with are suspiciously friendly and outgoing towards them, so much so that it makes the audience feel they can solve their problem easily. It’s only when they get into the down and dirty parts of this Los Angeles where their ordeal becomes too much to handle.

There is a dreamlike atmosphere and surrealism that permeates throughout this version of Hollywood, much of that being a signature of Lynch himself. Each character exists as a reaction to the world around them instead of dictating their own action. It allows for them to become susceptible to anything and everything making this mystery so scary and so absorbing.

2. Beau Travail (Claire Denis, 1999)

Has a war story ever been so artistically brave and vibrant than Claire Denis’s masterpiece Beau Travail? The film centers on Adjunct-Chef Galoup (Denis Lavant) as he remembers his time serving the French Foreign Legion in Djibouti. Much of the film is how Galoup is left to process the life around him that the younger soldiers are leading and how he responds to indifference while confronting his own insecurities.

To start, Beau Travail is less a story of hardened warfare as it is an operatic tale on the cost of restraints that the lifestyle and orders places on its soldiers. The film is based on Herman Melville’s novella Billy Budd and features music from the opera of the same name by Benjamin Britten. Many of the sequences in the film involve the other soldiers across from each other posturing and running drills together as the opera music crescendos. The way the drills are shot are more to accentuate the sensuality of masculinity on display as opposed to the grueling nature of the training these movies are more accustomed to showing.

The films ideas on manhood and fighting against a prohibitory regime leaves tangible room for the audience to draw their own conclusions to situations that are plaguing not just Galoup but other members of the troop. Beau Travail’s battles are the internal ones that are raging inside its characters making for bursts of emotionality that leave an indelible impact.

1. Playtime (Jacques Tati, 1967)

The idea of what a comedy is, or what genre can be, was pushed to its limits in Jacques Tati’s ground-breaking and transfixing Playtime. Centering on Tati’s iconic Monsieur Hulot character, Playtime follows that character as he tries to navigate a high-tech Paris but finds himself in increasingly humorous and audacious situations.

Playtime moves without form to great effect as it jumps from seamlessly from each encounter to the next as naturally as it can. The humor is unlike any other film in that the jokes function more as a water rapid of hilarity, meaning they come and go without warning or foresight and exist in their own space and the viewer simply needs to go along for the ride. Tati exhausts the various ways that he can make the audience laugh with sight gags, object humor and word play but disguises them all in this world of innovation. Nothing it set up but rather just exists like everyday life with all of its puzzling interactions.

But for as much as the film delights in its humor, the foundation that it has chosen to go with flows more like an observation of a city. This particular city of Tati’s hyper-modernist Paris does not fully understand the technology it possesses. There is no central plot, no acts, just moments of people trying to figure out the world around in which they sometimes succeed but also falter.

Tati never leaves the viewer on the outside though as he puts them right in the seat of his bumbling but kind-hearted Hulot. The audience sees the world through his eyes as he tries to figure out how to go about his life in a city that is becoming increasingly modernized and making the simple things about life so needlessly complicated to aggravating and uproarious effect.