Humans seek the comforts of religion for a diverse set of reasons, latching on to a shared mythos as a common shield against the unbearable unpredictability of life. There’s nothing as reassuring as assuming that there’s a perceived order and purpose to all of our occurrences — as despairing or chaotic as they might seem. Personal tragedy in particular triggers these spiritual inquiries the most — often serving as a coping mechanism against loss and hopelessness.

However, the path to enlightenment is not always a smooth one and is often riddled with an array of inner doubts and soul-searching. Crises of faith are as old as organized religion itself, and therefore one can’t be understood without the other. The delicate balance between individualism and the enforcement of religious dogmas has always proved to be a juicy subject, followed by a never-ending debate on religious institutions and their role in our society.

Cinema — the greatest ideological weapon and time capsule known to mankind — has repeatedly employed religion as a source for joy, pain and personal conflict. As a result, timeless masterpieces have ventured into the psyches of tortured souls reconsidering their faith — who end up rekindling with their beliefs in some cases or disregarding it completely in others.

Regardless of where your religious allegiances may lie, crises of faith as a narrative theme have gifted us with some of the most captivating stories ever put to film, including some from the best auteurs to ever pick up a camera. Against this embarrassment of riches, let’s take a look at this curated list featuring ten of the best overall.

1. Andrei Rublev (1966)

There’s a certain irony in cinema’s most spiritual director emerging from an atheist regime like the Soviet Union — especially one who wrestled at length with his own religious and metaphysical concerns throughout his work. Andrei Tarkovsky was the son of a successful poet — picking up his father’s lyricism as a filmmaker — a storyteller who always favored contemplative introspection over conventional narratives.

In Andrei Rublev — a historical epic chronicling the hardships and artistic endeavors of a 15th century religious icon painter — he perfectly captured the power of art and religion as beacons of hope and inspiration. For all his otherworldly talent, Andrei Rublev is tormented by the tragedy that surrounds him — from Tatar invasions to Pagan persecutions — and struggles to find inspiration for his work through his plight — losing faith in himself, his country and religion before eventually being encouraged by the work of another artist.

Tarkovsky argued that an artist should not see his work as an act of self-gratification but of sacrifice — it certainly feels as such in a turbulent era for a country ravaged by foreign raids and political turmoil. Art is only worth as much as it inspires people, and artists owe it to them to endure everything required to put their talent to use. One can only picture Andrei Rublev as a stand-in for Tarkovsky himself as two creators burdened with their talent, consumed by their work and fixated on their legacy — not to mention crippled by their circumstances.

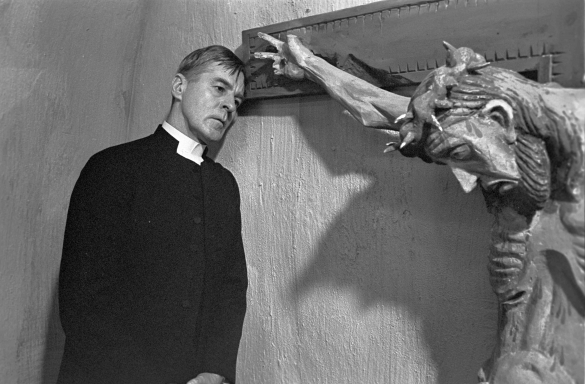

2. Winter Light (1963)

Arguably no director has pondered over faith as extensively or concisely as Ingmar Bergman did throughout his brilliant career. As a man haunted by his own mortality and existentialism, he showed as a filmmaker not to be bound to any genre but to his own spiritual turmoil. Winter Light followed previous attempts at articulating those inner doubts — from The Seventh Seal to Through a Glass Darkly — trying once again to bid farewell to his own Lutheran upbringing.

Winter Light came at the heights of the Cold War, a period of time where the dreadful prospect of nuclear annihilation clouded above everyone’s head, including some of film’s biggest auteurs — Kubrick (Dr. Strangelove), Kurosawa (I Live in Fear), Resnair (Hiroshima Mon Amour). This plays a crucial part in the storyline, where the main character — Thomas, an ill-ridden Swedish pastor — fails to provide counsel to a suicidal fisherman who comes to him terrified after reading an alarming article about China’s nuclear ambitions.

Thomas’ faith is further tested by his atheist mistress and his loyal sexton — in both cases rejecting their affection and insight with nothing but jaded indifference. How do you face and justify hopelessness — even as a true believer? For someone who’s based his whole intellectual backbone around his faith, failing to come up with an answer can prove to be the most frightening sight.

3. First Reformed (2017)

First Reformed is a movie that could easily be traced back to Bergman’s Winter Light and Bresson’s Diary of a Country Priest as the two biggest blueprints for its narrative. If the former used the nihilist anxiety that defined most part of the Cold War period as the trigger for Thomas’ crisis of faith, Paul Schrader’s movie revamped it to fit the generational concerns of its time. More than half a century later, it’s not nuclear bombs but climate change that troubles our society the most, and also what makes First Reformed main character — Pastor Toller — reassess his whole worldview.

Toller is in charge of a 250-year-old Presbyterian church that happens to be financially backed by the same shady owners of a nearby polluting factory. The priest is forced to confront his allegiance and the same religious dogmas he intones before the altar after being approached by the wife of a radical-environmentalist who’s suffering from suicidal thoughts.

Unable to soothe any ounce of her husband’s nihilism, we witness how Toller’s whole world crumbles down after coming to terms with how morally inconsistent and contradictory his institution — and therefore his whole spiritual frame of reference — has become.

4. Secret Sunshine (2007)

Humans are built to be gregarious in the face of tragedy, but Secret Sunshine lays down just how emotionally manipulative and opportunistic our social constructs can be.

The movie covers faith through the eyes of Shin-ae, a grieving young widow who decides to start over by relocating to her late husband’s hometown with her son. As if her recent tragedy wasn’t enough, her son is soon kidnapped and held for ransom — only to be found dead soon later.

In the face of such an unthinkable loss, Shin-ae struggles to come to terms with her new reality and — coerced by peer pressure — starts attending her local church meetings. Temporarily, she finds solace in her new faith and sense of camaraderie, but that comfort soon evaporates as she finds herself constantly judged by her own grieving process — to the point she’s reproached for not displaying enough emotion at her own son’s funeral.

Throughout the movie, Shin-ae goes full circle — from jovial agnostic to freshly converted — healing briefly through religion before realizing its shallow rationale. Secret Sunshine argues that, sometimes, no well-meaning support or coping mechanism can wipe out the ugly truths about life, and only by facing and accepting your pain can you truly overcome it.

5. The Last Temptation of Christ (1988)

Most of the movies featured in this list depict crises of faith from the perspective of plain believers, from priests to common folk. Next up we have one that similarly explores the spiritual endeavors of an individual seized by inner doubts — not a simple man but Jesus Christ himself.

Martin Scorsese is not even close to being the first director to depict Jesus on the big screen. As long as cinema has existed, Catholic stories have been repeatedly brought to life — some in epic fashion with gargantuan productions — and in many cases the life of the Messiah has taken center stage.

However, what sets this movie apart — and equally enraged certain radical Catholic circles that tried their best to censor it — is the way it approaches a bigger-than-life figure with a braver outlook than the rest. Instead of portraying him as a morally flawless character above any kind of moral reckoning, Jesus is seen here as a man burdened by his role of savior, inherently flawed and doubtful — forever tempted by the same lust and vanities as the rest of us mortals.

The most famous sequence occurs during Jesus’ Crucifixion, where he’s tricked by Satan to escape death — imagining an idyllic life free of any divine purposes as a married man to Mary Magdalene, raising a family in an extended vision — before overcoming his temptation and accepting his role as the Messiah.