6. Henry: Portrait Of A Serial Killer (1986)

As lean and mean as cinema comes, Henry: Portrait Of A Serial Killer’s 83 minutes are as sharp and cold as a paring knife. A study of serial killer Henry (played with menacing control by Michael Rooker) and his relationship with accomplice Otis and Otis’ sister Becky, it’s a disturbingly realistic drama, one that’s punctured by occasional acts of horrifying violence.

The low-budget but impressive cinematography makes excellent use of the gritty Chicago setting. It’s a grimly urbane film, taking place in back alleys, underpasses, quiet street corners and the main characters’ rundown apartment block. Much of the action takes place at night time, on the city’s eerie and chilly streets. Only at the start and end do we see shots of the countryside, as Henry makes his way into, then departs, Chicago. It’s as though he’s entering and exiting the belly of a beast, one that’s as unforgiving and vacant as him.

This vacant quality is what makes the whole film and particularly Rooker’s performance so chilling. There’s no exaggerated menace to his performance, just an ice-cold blankness, a void where humanity should be. The grimy Chicago locations mirror this emptiness. Perhaps due to the film’s minimal budget, these locations have an authentic quality to them, appearing as the types of place where a serial killer really could commit an inexplicable act of terrible violence.

7. The People Under The Stairs (1991)

The late eighties through to the early nineties saw an explosion of cultural consciousness from America’s inner cities. Hip-hop on both coasts was turning into a world-beating art form, while films such as Do The Right Thing, Boyz N The Hood and Menace II Society became major hits, portraying a world that had until then been underrepresented in mainstream culture.

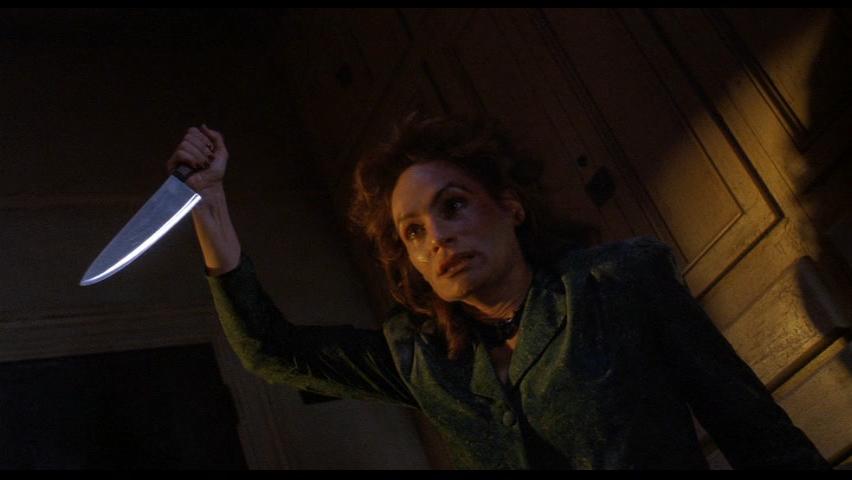

Wes Craven’s The People Under The Stairs takes place in this milieu, refracting the struggles of inner-city America through a satirical horror lens. The legendary director’s first feature of the nineties follows a trio of burglars who, faced with eviction from their apartment complex, break into their landlord’s home and make a horrifying discovery in the basement. While Craven’s socially conscious messaging is hardly subtle, the film succeeds as a constantly surprising and gleefully over-the-top shocker. The discovery that the lead characters make is truly scary, functioning as both a darkly-comedic nightmare as well as a brute-force metaphor.

The villainous landlords are portrayed as archetypal extreme conservatives (interpreted by some as Ronald and Nancy Reagan in disguise), concerned only with their own definitions of law, order, family and wealth. They make for fabulously nasty villains, as much so for their gentrification plans as their macabre secrets. It’s a fun and underrated movie, one that’s as unashamedly outraged as it is gleefully nasty.

8. Candyman (1992)

For many, Candyman will be one of the first films that comes to mind in reference to urban horror. Almost a sister feature to our list’s previous installment, few films before it had been set so pointedly in impoverished inner-city America. However, whereas The People Under The Stairs is a brash horror-comedy delivered with sledgehammer force, Candyman is a poetic meditation on race relations and the fearsome power of folk tales.

Candyman’s narrative follows semiotics student Helen (played by Virignia Madsen) who investigates an urban legend that has spread across inner-city Chicago. She traces its origins to the Cabrini-Green public housing complex and uncovers the tragic tale of the titular supernatural character. Helen’s possible ‘white savior’ status is smartly subverted. Her role in the narrative becomes less and less significant as we learn more about Candyman and the two’s fates become inexorably intertwined.

The film’s portrayal of an inner-city housing project is impressively realized. It’s a place decimated by urban decay and police inaction, who respond immediately when Helen is threatened but have let countless other crimes go unsolved. The film’s central metaphors are complex and open to interpretation, however, Candyman’s sharp portrayal of an urban space that’s been obliterated by years of systemic inequality is startlingly clear.

9. Tales From The Hood (1995)

The final ghetto-set horror film from the nineties on our list is Rusty Cundieff’s portmanteau horror Tales From The Hood. Like most portmanteau films, certain sections are stronger than others, however even the less impressive ones are smart, visceral portraits of the struggles of Black America. Each of the four tales tackles different socio-political issues, extrapolating and unpacking them as fun, silly and occasionally-creepy parables.

The best and most unnerving section is ‘KKK Comeuppance’. The tale of ghostly slaves taking revenge on a racist Southern senator, it features spooky dolls, voodoo magic and a memorably creepy painting. Others feature zombie vengeance against racist cops, an uneven domestic abuse allegory and a hallucinogenic final section that attempts to provocatively skewer gang violence. These segments’ tones aren’t exactly nuanced or considerate, but succeed as entertaining satirical horror.

Tales From The Hood is far from perfect. However, its macabre metaphors for some very real struggles are never anything besides compelling and deeply felt. It says a lot about how little the black experience has been represented in horror cinema that Cundieff could only get two sequels to the films funded following the success of 2018’s Get Out, twenty years later. Here’s hoping that horror continues to open itself to new perspectives.

10. Pulse (2001)

It feels apt to end our list of horror films set in urban environments with a film that suggests our physical reality is starting to blur, via our interaction with digital technology, with that of the metaphysical realm. Set in a never-more-gray Tokyo, Pulse is a sad, forlorn ghost story that ambiguously questions our increasing dependence on modern technology.

The opening section of Pulse contains some of the most chilling sequences in the whole of horror. It slows down somewhat following this incredible opening half hour, before picking up again towards its grandiose climax. The film portrays modern life as defined by sad isolation, a milieu that the Tokyo setting defined by tiny apartments, smog-leaden skylines and empty streets all contribute to. The main characters often congregate in a greenhouse atop a tall city building – another atomised zone in a lonely, unknowable world.

The plot becomes highly convoluted, but it doesn’t really matter. Pulse makes sense on a deep emotional level. The uncanniness of digital life is something we have all felt, more so now than ever, over twenty years after the film’s release. Director Kiyoshi Kurosawa sharply entwines this feeling with the film’s urban setting, which is portrayed as a place of eerie isolation, in spite of its sprawling scale. Pulse is a modern horror masterpiece, one that gets more ominously insightful day by day.