6. Caché (Michael Haneke, 2005)

In an insidious mystery resembling David Lynch’s Lost Highway, a Parisian couple, Georges (Daniel Auteuil) and Anne (Juliette Binoche) receive anonymous video tapes and drawings delivered to their home. The tapes show hours of their house being filmed and the naïve drawings depict a child with its throat slit. Georges begins to suspect the culprit is Majid (Maurice Bénichou): an Algerian orphan who lived with Georges’ family growing up.

British newspaper The Times rated Caché as “the best film of the noughties.” With reference to the 1961 Paris massacre, the film examines the repercussions of France’s colonial history in North Africa, dramatising the overwhelming trauma this has caused the Algerians. Haneke uses the thriller genre as a receptacle for a social critique of oblivious white privilege and racial scapegoating. He unveils the institutional prejudice persisting into the 21st century, showing how history repeats itself unless humanity can move towards empathy. As “history is written by the winners,” for once, the Algerian perspective is heard and honoured.

More expansively, as well as voyeurism, Caché considers the impact of our past transgressions upon the present. “How do we treat our conscience and our guilt and reconcile ourselves to living with our actions?” asks Haneke. In many regards an anti-film, the unconventional Caché will not give audiences what they want, but rather what they need. There’s a palpable message, yet also an imaginatively stimulating space for multiple interpretations, devoid from mainstream filmmaking. Caché’s captured with an unsettling realistic, cheap digital camera, long takes, practical lighting and a grey colour palette inducing dread.

7. A Bittersweet Life (Kim Jee-woon, 2005)

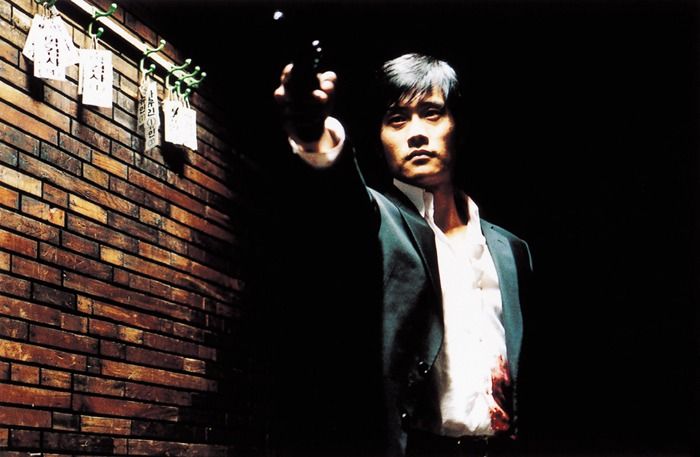

This South Korean action thriller begins with a shot of leaves rustling in the wind. Enforcer Kim Sun-woo (Lee Byung-hun) is dispatched by his boss, crime kingpin Mr. Kang (Kim Yeong-cheol), to monitor his mistress Hee-soo (Shin Min-a). Kang believes Hee-soo is having an affair. He instructs Kim Sun-woo to kill her and her lover if this is the case.

The remarkable choreography, graphicness and intensity of the martial arts in great South Korean films makes American action movies look like kindergarten games, especially in the hands of auteur Kim Jee-woon. Integrating all the trademarks of neo-noir, from black suits to neon clubs to dark humour, he delivers both a classic gangster flick and a cautionary tale of male pride and reactivity. The narrative delves into the dichotomy of humanity versus duty, in addition to Marxist tenets of mutiny and disobedience.

The ferocious violence is balanced by moments of sentimentality, such as an elegant closeup of Hee-soo’s spine and shoulder filmed from behind. A Bittersweet Life was the movie that solidified Lee Byung-hun’s reputation as a prominent action star in South Korea, yet the piece remains little-known outside the country. It’s the zenith of neo-noir, satisfying all of one’s genre expectations, yet also provoking rumination and introspection.

8. Pusher 3 (Nicolas Winding Refn, 2005)

Pusher 3 is set over the course of 1 day in Copenhagen. A Serbian mob boss called Milo (Zlatko Burić) is double-crossed during a drug deal. Whilst cooking for his daughter Milena’s (Marinela Dekic) birthday party and struggling to stay sober, Milo faces the impending wrath of his Albanian suppliers. Akin to its predecessors, Pusher 3 can be enjoyed as a standalone piece.

Whilst the second instalment of the trilogy is usually regarded as the strongest, despite rave reviews, Pusher 3 is overlook, both by non-Danish audiences and Refn himself. Although Milo’s introduced in the first film as a dangerous force, in Pusher 3, Zlatko Burić is given the opportunity to explore’s Milo’s complexity, focusing especially on the humanising struggle of his heroin addiction.

Burić’s sensational, believable performance shows audiences the reaches of Milo’s personality: his affection for his daughter, his viciousness, his vulnerability. Milo is not as simple as a straightforward villain. Through fluid dialogue, Refn’s character study toys with the audiences morals by warming Milo to them, while also exhibiting his brutality. Consequently, it is hard to wholeheartedly like or dislike Milo.

This has the effect of holding a mirror up to the audience, so that they become aware of their own prejudices when judging others based upon their occupation or background. Additionally, like its predecessors, the violence in Pusher 3 is so jaw-dropping, it becomes difficult to endure. In contrast to other neo-noirs, its de-glamorization of a life of crime serves as a staunch caution to viewers, intensified by the realism of its documentary camerawork.

9. The Limits of Control (Jim Jarmusch, 2009)

“An action film with no action.” A taciturn, Delon-esque loner (Isaach de Bankolé) is hired to complete a clandestine criminal mission taking him across Spain. He encounters a cast of unusual characters (Tilda Swinton, John Hurt, Bill Murray et al.) while consistently drinking 2 espressos at every café he visits. Each acquaintance hands him a matchbox directing him to his next location.

Confounding all the expectations of a hitman movie, this minimalistic, enigmatic, atmospheric film crafts a quiet, Buddhistic tone reminiscent of Jean-Pierre Melville. Its cinematography and moody lighting celebrates the poetry of banal, everyday life. Misunderstood upon its release, Jarmusch strips down all the crime genre’s elements to create an inverse of formulaic, preachy, blockbuster moviemaking.

“I’m not a didactic filmmaker,” explains Jarmusch. The Limits of Control is a countercultural picture that eschews the imposition of a clear moral, promotes imagination and encourages subjective interpretation. Jarmusch not only permits his audience to draw their own conclusions from the narrative, but provides a liberating, divisive canvas which subtextually criticises psychological modes of control in western society.

“Bill Murray’s character says something that was told to me over and over in my life by authority figures, which is: ‘you just don’t understand the way the world really works,’” relates Jarmusch. “And I’m just fed up of hearing that because the world works the way your consciousness can perceive it. Whatever people tell you is real is based on some ulterior motive on their part. The film is interpretable by anyone in their own way and that’s sort of the point.”

10. Perrier’s Bounty (Ian Fitzgibbon, 2009)

Michael McCrea (Cillian Murphy) is given until the end of the day to pay his debt to Dublin godfather Darren Perrier (Brendan Gleeson) or face execution. With the help of his friend Brenda (Jodie Whittaker) and father Jim (Jim Broadbent), Michael frantically attempts to roundup the cash.

Despite its poor reviews, Perrier’s Bounty is in fact a fun gangster road movie, enlivened by its comedic dialogue, bulging suspense and gunfight sequences. Jim Broadbent is laugh-out-loud as a coffee grain-guzzling man afraid he’ll die the next time he falls asleep. Likewise, Brendan Gleeson also flexes his dry comedic muscles, in a role mirroring his work in John Boorman’s The General (1998).

What is more, his sensitive mobsters are comically realistic, professing their own share of witty, absurd exchanges, rooted in a regional Dublin feel. Meanwhile, Cillian Murphy and Jodie Whittaker demonstrate they’re strong, interesting leads, foreshadowing their work in Peaky Blinders and Doctor Who, respectively. In spite of having a predictable plot, Perrier’s Bounty’s an enjoyable, funny piece of escapist entertainment for a night-in.