5 and 4. Heist (David Mamet, 2001) and The Score (Frank Oz, 2001)

What a breezy double feature these two make! Two largely left behind films starring industry legends about how sweet it is to be an old head in a business defined by impulsive up and comers. For whatever reason, neither left much of a cultural impact. Despite starring Gene Hackman and receiving half decent critical reviews, Heist actually lost about $10 million off its modest $39 million budget. The Score did decent business and earned sincere pats on the back from critics like Roger Ebert and Peter Travers, but for a well-paced heist flick starring Robert De Niro, Edward Norton, Angela Bassett, and boasting Marlon Brando’s final performance, this movie feels like it should have left a much bigger footprint than it did.

At the time, most considered Heist and The Score little more than popcorn flicks—to their credit, neither film iterates much on the genre—but it’s also possible to attribute the lack of cultural resonance up to bad timing. 2001 was an apex year for modern heist movies with the more traditional projects overshadowed by the stylistic ingenuity of Ocean’s Eleven.

How closely these films overlap is indicative of their lack of originality. How entertaining they are illustrates how little it actually matters. Hackman and De Niro both star as wily thieves predicably trying to complete one last job before riding off into retirement with their criminally underwritten love interests—Hackman wants to sail around the world with his young wife (Rebecca Pidgeon), De Niro hopes to buy out the mortgage on his Montreal jazz club and convince his jet-setting girlfriend (Angela Bassett) to finally settle down. Complications arise when they are forced to team up with arrogant young guns (Sam Rockwell and Edward Norton) eager to bite off more than they can chew. Each film flies through an hour of the nitty-gritty technical planning that heist films are bult on, before, inevitably, the young bucks get greedy and complicate otherwise well laid plans.

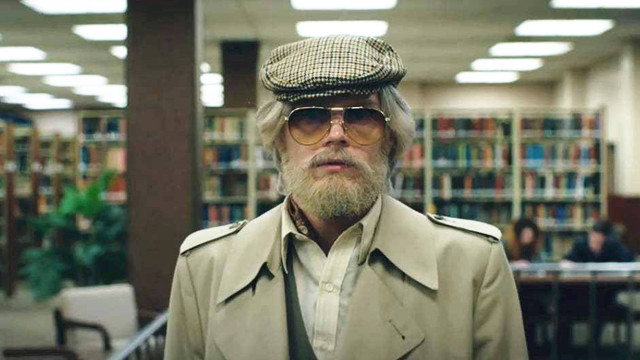

Of all the reasons to watch these movies (to name a few, David Mamet’s standout script for Heist, Robert De Niro explaining safe technology, and the incredible chemistry between Hackman and his sidekicks, Delroy Lindo and magician Ricky Jay), Marlon Brando’s performance as Max, a washed up crime puppeteer funding De Niro’s operations, takes the cake. Just three years before his death at the age of 80, Brando is impossibly alive in this part. He’s not in much of the movie, but he’s the best of it and it can’t work without him. Max, an old, indebted criminal, is both a success and a cautionary tale for those invested in the thieving underground. He’s made it. He’s not in jail or dead prematurely. He wears lavish robes, drinks champagne constantly, and owns an enormous Montreal mansion.

At the same time, having never really left the game, he’s desperate, unable to escape the hollow shell he clings to. His ornate lifestyle has him indebted to dangerous people. His mansion is devoid of human life, complete with an empty indoor pool that he dangles his silky slippers into as he sips his sparkling wine. All he has to cling to is his working friendship with Nick (De Niro) and the faint hope of a giant score.

It’s not hard to see why Brando chose to participate in his film. For one, he got to work with the other Vito Corleone almost thirty years after The Godfather. But perhaps more importantly, Max must have been an appealing mirror for Brando, whose health and personal relationships fluctuated wildly in the final decades of his life. In his career and his personal life, Brando was always a figure on the extremes. Between the massive peaks of On the Waterfront (1954) and The Godfather (1972), Brando starred in endless flops and saw his public estimation tarnished.

By the time The Score came around, Brando was often hooked on oxygen and spent weeks on end at Michael Jackson’s Neverland Ranch (the spiritual cousin of Max’s Montreal mansion). That he had the self-awareness to play Max—and to play him with, as Peter Travers wrote, “eyes alive with mischief”—speaks to Brando’s brilliance, to his singular ability to captivate the camera as everything around him falls apart.

3. American Animals (Bart Layton, 2018)

Early in American Animals, Spencer Reinhard (Barry Keoghan) attends a frat party. He’s pledging, so he goes up on stage to recite something useless he’s supposed to have memorized, but when he doesn’t do it with enough gusto, the drunk tank tops in the Transylvania University crowd jeer him off the stage, then make him suck beer from a hose coming out of another frat boy’s fly. He leaves dejected, not because he’s disappointed that the frat boys didn’t accept him, but because even if they had, he still wouldn’t have been satisfied. Monotony and the purposelessness it inspires are the enemy for Spencer. So, deep in the throes of a specific sort of cis-male apathy, Spencer and his friend Warren Lipka (Evan Peters) dream up a scheme to steal Transylvania’s collection of valuable rare books. Warren wants to break things. Spencer wants to stop waiting for something to change his life. They recruit a few friends and break a fluorescent tube of angst over the blue Kentucky doldrums just to inhale the fumes.

To tell this story—a thoroughly researched representation ripped from the pages of perpetrator Eric Borsuk’s autobiography—director Bart Layton blurs the lines between drama and documentary. A documentarian by trade, Layton weaves into this dramatization interviews of the actual people involved in the heist. Some scenes include the actors and real people talking, or gazing at one another from opposite sides of a car as it drives by. It’s shocking the first time it happens. About sixteen minutes into the film, Warren Lipka pops up in a car beside Evan Peters. Peters asks him if the events unfurling in the scene are how he remembers them. When Lipka says no, it lays the groundwork for what’s to come—Layton’s clever investigation of the porous boundary between perception and truth, or of whether recollections can ever be “true” at all.

Thankfully, Layton never lets the movie devolve into existential dribble. He’s not too clever for his own good. The muddied waters of the real and the dramatized serve as a propulsion system for the plot, which he never loses sight of. Layton understands that underneath all of his unanswerable questions is a heist film wrought with the tension of restless young men and the dangerous decisions they make to assuage their egos. For a movie located at the toxic intersection of power and amateurishness, there is nothing amateurish about it. Layton’s vision is clear, and his execution is precise. The lingering question for viewers is whether this fresh style is repeatable, whether Layton trailblazed a new path for telling true stories in film, or whether American Animals will be an inventive one-off worthy of the esteem it deserves to accrue over time.

2. Inside Man (Spike Lee, 2006)

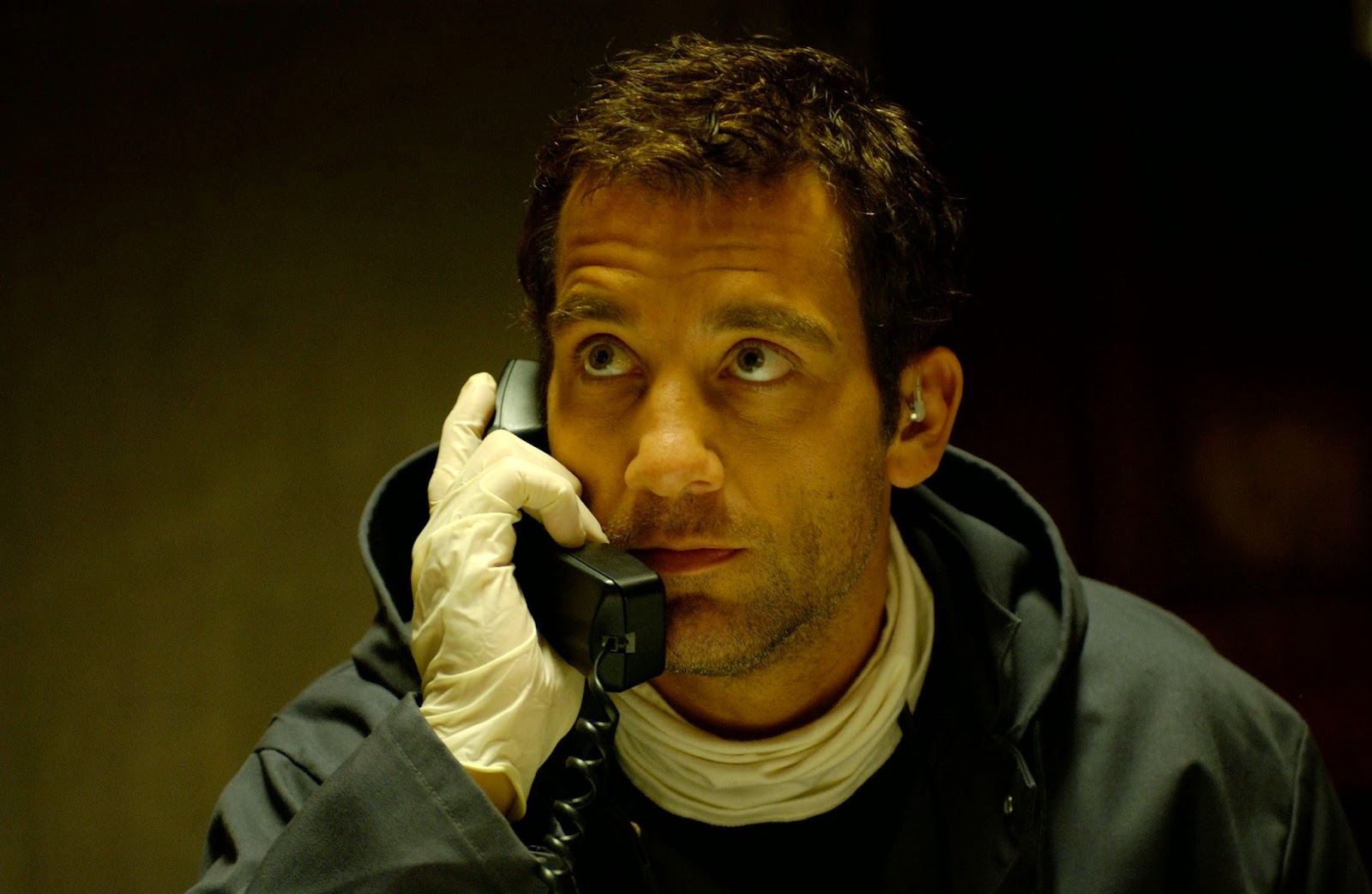

Of all the films on this list, Inside Man is almost certainly the most seen and might be the most critically acclaimed, and yet it’s still underappreciated in the Spike Lee extended universe. Inside Man exists in its own little corner of Spike’s filmography. It’s one of only six features that he didn’t write, and it’s the only film in his library that he didn’t produce. (Ron Howard was allegedly first in line to direct this film but bailed on the project to make Cinderella Man. Thank goodness for that.) The auteur took the project because he thought highly of Russell Gerwitz’s script, likening it to a contemporary Dog Day Afternoon. And really, no one but Spike Lee could have made this film into what it is. The script could easily have been reduced to a traditional popcorn heist flick, but Lee saw the heist as a gathering place for New York’s endless personalities. As always, he imbues the film with ideas, this time about identity greed, and the racist incompetence of the NYPD.

Reuniting with Spike after the successes of Malcolm X and He Got Game, Denzel Washington stars as Keith Frazier, a down on his luck NYPD detective called in to manage a bank robbery and hostage situation in the financial district. The audience follows Denzel as he uncovers the unique motives of his foil Dalton Russell (Clive Owen) and manages the egos of adversarial colleagues and an arrogant fixer (Jodie Foster) called into the scene to protect the bank owner’s (Christopher Plummer) sensitive property.

The heist in Inside Man isn’t devoid of nitpicky flaws, but it’s irrelevant. This film is on fire from the moment the camera zooms in on Clive Owen’s smirk. Denzel is always brilliant, but Lee seems to be able to get out of him an extra five percent of attitude that no other director can (save maybe for Antoine Fuqua). And they know how great they are together. The two can’t help but nod to their collective greatness as Denzel boasts an elaborate hat and cocky walk that evokes the iconic strut at the beginning of Malcolm X. It’s not Malcolm, but Keith Frazier is one of Denzel’s all-time great characters. He has everything one could possibly want in a Denzel performance: charm and command covering just the subtlest sensitivity. It’s also one of Denzel’s funniest roles. His line reading is off the charts, and there’s a moment toward the end of the film when he’s walking down the street with Chiwetel Ejiofor and his laughing smile feels like it’s going to burst off the screen. For Denzel, alone Inside Man is worth the watch.

1. Nine Queens (Fabián Bielinsky, 2000)

To paraphrase Syndrome, the iconic villain from 2004’s The Incredibles, if everyone is a conman, is anyone really?

Nine Queens toes the thin line between a heist and a conman film, though in the end it probably skews toward the latter. Even if it’s not a heist film by definition, it certainly feels like one in the end. When the mechanics of the elaborate scheme to steal a small fortune are revealed, it’s every bit as exciting and surprising as the ends of Ocean’s Eleven, Inside Man, or any of the century’s best thieving games.

Bielinsky’s debut revolves around two conmen. Marcos (Ricardo Darin) is a veteran looking for a partner to run small jobs with. He recruits a greenhorn, Juan (Gaston Pauls), to the game after watching him confuse a convenience store clerk into forking over some extra change. After grabbing some petty cash from restaurants and old folks, Marcos’ former partner presents the pair with an opportunity to sell a counterfeit set of the nine queens—an extremely valuable group of stamps from the Weimar Republic—to a powerful collector. They have twenty-four hours to complete the job, which, naturally, unravels into a quest far more complex and perverse than they could have ever imagined.

The film’s heart beats through the performances of its two leads. Bielinsky sets them up as natural foils. Marcos is a lecherous, deplorable person. He is shameless, willing to screw over anyone—including his own siblings—to garner just a bit more wealth. Juan is a baby-faced newbie others seem to implicitly trust. He’s in the game to collect bribe money that will spring his dad—from whom he learned his tricks—from prison. Together, Pauls and Darin have a natural chemistry. Pauls plays Juan softly, allowing Darin to infuse the screen with his bitter wisdom and ruthlessness. And Bielinsky’s deft touch ensures that no one is quite as they seem.

Like The Aura (but far more explicitly), Nine Queens exudes an atmosphere of desperation amidst a national economic collapse orchestrated by the real cons—those frauds of the highest order with the power to destroy communities. Under the crushing weight of broken institutions, Bielinsky asks what it means for someone to lie and cheat as harshly as Marcos does? Does it even count as cheating when the game is a deception in the first place?

It’s a rare achievement for a heist movie to embody social critique so effortlessly. Bielinsky knew what he was doing and, as if ripped right from the Nina Simone quote, believed it was his work’s responsibility to reflect the present circumstances. It was challenging for him, actually, when Nine Queens became such a success in his home country. As Argentines continued to suffer through a debilitating crisis, the film’s plaudits earned Bielinsky more financial stability than he’d ever had.

It’s easy to wonder if this dissonance led to such a drastic shift toward confusion and melancholy in The Aura, but Nine Queens is a lucid, airy film. It knows where it’s going, so even when the finely tuned gears begin to sputter, Bielinsky’s steady hand keeps the viewer entranced with a captivating, lived in atmosphere. Almost twenty years after his death, no one’s made a movie quite like it.