This list may cause some double-takes. They directed THAT? No need to check IMDb for fact-checking. It may be impossible to imagine, but these anonymous films were created from the visions of established auteurs with distinct stylistic and thematic throughlines. These directors took on these films for financial purposes, just as a change of pace, or for unknown reasons, which will only further complicate their draw to these projects.

1. Sidney Lumet – The Wiz (1978)

In essence, the “working man’s” director, Sidney Lumet worked frequently and would try anything. He had an admirably non-fussy approach to directing and his view of himself as an artist. Having said that, the one film of his that sticks out among the variety of his 30+ movies is The Wiz. For Lumet, one would expect gritty streets of New York, police corruption, underdogs and outcasts, the collateral damage of crime, and a grounded examination of societal issues. But a film adaptation of a Broadway musical retelling of The Wizard of Oz? That is pushing it. A Lumet Oz adaptation would only make sense if the Wicked Witch of the West had to face trial in the Emerald City.

The film follows the same plot outline as the original Oz, this time with Dorothy (Diana Ross) as a young schoolteacher in Harlem who is transported to a magical version of New York City. As the story goes, she befriends a Scarecrow (Michael Jackson), a Tin Man (Nipsey Russell), and a Cowardly Lion (Ted Ross) on her journey to be sent home by the Wiz. The film’s commercial and critical failure came at a time of turnover in the movie landscape in 1978. It was a signal that New Hollywood and Black Cinema (starting with the Blaxploitation movement earlier in the decade) were fizzling out.

Lumet’s voice as a director helped define ‘70s cinema, and The Wiz could only have been released during an era when his films Serpico, Dog Day Afternoon, and Network were in the zeitgeist. The film leans into more of an off-beat tone, especially compared to the 1939 classic. The shadow of the original loomed over the 1978 film, so Lumet had to take risks in order to make the film unique.

While heavily flawed, mainly due to its uneven pacing and questionable casting, there is an undeniable quality to the film’s charm, which is attributed to Quincy Jones’ music supervision and engaging blend of fantastical set pieces and real NYC locations. When the film is at its worst, everyone wishes the studio would receive a mulligan and find a more suitable director. However, Lumet’s humanist and grounded approach to storytelling lends The Wiz a flavor that speaks to the moment.

2. Robert Altman – Popeye (1980)

New Hollywood directors of the 1970s never came out the same as they originated during this fruitful time for filmmaking. By 1980, the year of the release of Popeye, the film landscape was drastically changing, morphing into an industry dominated by franchise blockbusters that mirrors the contemporary status of cinema. While the days of M*A*S*H and Nashville being produced were outnumbered, the inaugural year of the ‘80s featured many last gasps of New Hollywood, with few odder than Popeye, a film by Robert Altman. The same one that made McCabe & Mrs. Miller.

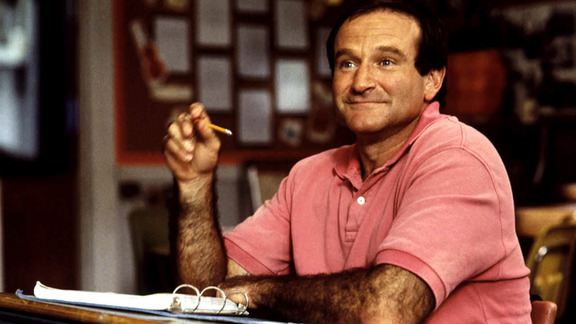

The film is certainly an outlier concerning its subject and setting. Altman deals with some of the most human characters ever displayed on film, and depicts them in grounded and mundane environments. The director shifted to a more outright formalistic approach with his unique spin on Popeye (Robin Williams) and his adventures with his friends in the seaside town of Sweethaven. Heavily panned at the time of its release, but as often the case with misunderstood flops, Popeye has been reclaimed by many in retrospect, because at its core, this is not a shameless money grab to cash in on the Popeye property.

The genius of the film is that it leans into its Altmanesque quality. Only he could have channeled his unique vision into something so anomalous. The commitment to farcical and cartoon-like language combined with the traditional Altman overlapping dialogue and dynamic camera zooming amounts to a film that frantically subverts expectations to such a degree that hamstrings enjoyment on the initial viewing. On a closer examination when revisiting, the mastery at hand is impeccable and should inspire limitless curiosity.

3. Walter Hill – Brewster’s Millions (1985)

He will never be confused with the sharpest comedic minds, but Walter Hill dabbled in humor with action buddy-cop movies like 48 Hrs. and Red Heat, and achieved his most artistic success with gritty and visceral crime thrillers like The Warriors and The Driver. However, when he is granted the opportunity to direct a pure screwball comedy in Brewster’s Millions, the result will be a bizarre misfire. As it turned out, as most likely the case with many of these entries, Hill admitted to signing on to direct the film for a healthy paycheck.

Brewster’s Millions, based on a book by George Barr McCutcheon, features one of the most baffling plots to ever hit the screen. A minor-league baseball player, Montgomery Brewster (Richard Pyror), is forced to spend $30 million within 30 days in order to inherit $300 million from a late relative. However, the deal will be voided if he owns any of his pre-existing assets, destroys the money, donates it, or informs anyone of this deal. Movies of the mid-80s often felt like they were written on the fly, and this film stays true to that phenomenon.

The film operates as a system to integrate Pryor into wacky comedic setpieces, including a bid for mayor and purchasing the New York Yankees to face off against him on the mound. The problem lies not in its choices, but it’s execution. Hill demonstrates shallow awareness of what makes comedy work. In general, Brewster’s Millions is as if aliens came down to Earth and attempted to make a traditional American comedy. For a director who usually understands the rhythmic beats of genre, Hill’s sense of humor was a lackluster showing.

4. William Friedkin – Blue Chips (1994)

Cops, criminals, demons, and college basketball coaches and players. These are all subjects of the filmography of William Friedkin. One of the most vibrant filmmakers of the New Hollywood, churning out essential texts of the period such as The French Connection, The Exorcist, and Sorcerer lost his ways in the following decades and took on projects less suited to his abilities. The most pointed outlier of his, Blue Chips, is simultaneously an on-brand Friedkin picture that is lacking a proper voice.

A pressing issue at the time of its release in 1994, Blue Chips engaged with the controversial practices of NCAA college basketball recruitment. The film follows the Western University Dolphins basketball program and their head coach, Pete Bell (Nick Nolte), succumbing to unethical means of buying recruits to play for them, including a newfound, other-worldly talent in Neon Boudeaux (Shaquille O’Neal). Friedkin’s raw, documentary-like filmmaking is present in the film’s casting of real NBA stars in Shaq and Penny Hardaway and during the game sequences. There is a lively energy when watching these games that are not overly glamorous. In addition, Nolte is believable as a hard-headed and influential college basketball coach in the spirit of Bobby Knight.

Where this film is weakened is in its formless narrative. For as much as Blue Chips wants to be defined by its unflinching attitude towards exposing the corruption within the NCAA, it is commonly toothless. Friedkin has shown to direct with a sharp tongue before, but it is restrained far too often. The grueling work environment of a major conference basketball organization or the personal turmoil that Coach Bell would ensue is left slightly undercooked. Albeit an enjoyable picture, the fact that the director of Sorcerer has a finished product that is lacking in harshness causes the film to be somewhat of a blown opportunity.

5. Francis Ford Coppola – Jack (1996)

At the peak of their powers, no director had quite the artistic brilliance of Francis Ford Coppola in the 1970s. After giving the world The Godfather, The Godfather: Part II, The Conversation, and Apocalypse Now, he lost his way, thus causing him to lose his finances. From there on out, he made some odd career decisions, none more baffling than the 1996 film that presupposes, what if Robin Williams starred in Big? The result: Jack.

A frequently schmaltzy actor in Williams starring in schmaltzy ‘90s Oscar bait seems like a bad punchline. Williams stars as a ten-year-old boy named Jack who, due to an abnormal health condition that causes him to age four times as fast as the average child, is trapped in a 40-year-old man’s body. On paper, this character is bound to enable his worst tendencies as a performer, and Coppola delivers on that potential.

Let the record be known that this is not a family picture, as indicated by the PG-13 rating. Yet, the film has a peculiar juvenile sensibility, and its contradicting tones of comedy and coming-of-age saccharin cause Jack to be wildly uneven and ambiguous in its intent. By no means is the film offensive to any of the human senses, but Coppola’s attempts to craft a profound narrative amid goofy Robin Williams antics fall flat on their face. There is a desperate bid to conduct a sweeping dramatic arc of the Jack character in the spirit of Michael Corleone or Harry Caul of The Conversation, but that level of respect for the characterization is never earned.

Coppola has expressed his approval of his film in the past, finding it “sweet and amusing.” The director claimed that he is “always happy to do any type of film.” A filmmaker with the stature of Coppola taking on Jack is more daring and ambitious than anything he demanded while on the set of Apocalypse Now.