10. Ocean’s Eleven (Steven Soderbergh, 2001)

Upon leaving prison, Danny Ocean (George Clooney), gathers a group of eleven people to plot a Las Vegas casino heist. But not just one, three popular Las Vegas casinos. Technically a remake of the 1960 Rat Pack film of the same name, the script was penned by Ted Griffin and directed by Steven Soderbergh. Soderbergh was coming off a pretty hot run with previous film such as Erin Brockovich, Traffic and Out of Sight.

The film retains its 60’s predecessor’s elegance and charm, as Clooney and Brad Pitt dial up their charisma and likeability up to one hundred. What makes the film special is the supporting cast. You have Julia Roberts, Elliot Gould, Bernie Mac, Casey Affleck, Scott Caan, Don Cheadle, Carl Reiner, Matt Damon and Andy Garcia. The film is fast paced, smartly edited, witty, cool and stylish. If Swingers was the type of film that made you want to get the hell out of Vegas, then Ocean’s is the film that makes you never want to leave.

9. Dog Day Afternoon (Sidney Lumet, 1975)

With origins in theatre and an exciting Hollywood beginning in 1957 with the hit film 12 Angry Men, Sidney Lumet really mastered his craft in the early 70’s, becoming one of New Hollywood’s most powerful directors. His gritty New York stories, his realist characters that hold an incredible depth, the neo-realism he takes from Italy and brings to America, it’s what makes him great and Dog Day Afternoon remains his best, in some people’s opinions.

The film is based on the Life magazine article “The Boys in the Bank” by P.F Kluge and Thomas Moore, telling the story of the 1972 robbery led by John Wojtowicz (played by Al Pacino with the name changed to “Sonny”) and Salvatore Naturile (John Cazale as “Sal”) in a Chase Manhattan branch in Brooklyn. The film begins and acts out as a standard “heist gone wrong” formula, but soon becomes a social commentary on the police as Pacino’s character challenges and criticises the surrounding NYPD about the Attica police riot in 1971, gaining the support of the public watching the hostage situation. The film is at times comedic, upsetting, uplifting yet tragic. Pacino and Cazale’s performance not only remind us of the obscene talent that was available in the 70s, but also that of Sidney Lumet.

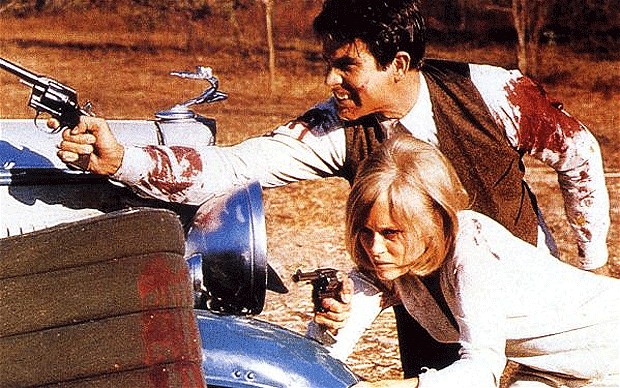

8. Bonnie and Clyde (Arthur Penn, 1967)

Bonnie and Clyde is one of the most significant films ever made. It was released in 1967, a moment in history where Hollywood was just on the verge of changing forever, and this film is what accelerated that change. The film tells the story of the real-life couple Bonnie and Clyde who robbed banks and committed murders during the Great Depression. Arthur Penn is just as important as the film, he was one of the founding fathers of the New Hollywood movement and influenced many filmmakers yet to come.

Warren Beatty and Faye Dunaway play the leads and are just as beautiful as each other. But the film also includes a great supporting cast with early roles from Gene Hackman and Gene Wilder. Penn was influenced by the French New Wave and used rapid shifts of tone, choppy editing and graphic violence in the film, all choices that made the film stand out in 1967. The film was a great success, critically and financially, but most importantly it showed not only what a gangster/crime film could look like…But any film.

7. Bob the Gambler/ Bob le Flambeur (Jean-Pierre Melville, 1956)

Bob le Flambeur is one of the most influential films of all time. Not only did it influence Tarantino’s writing style, or Soderbergh, or Paul Thomas Anderson, but most importantly it influenced and helped the Nouvelle Vague (French New Wave) discover their style. The film uses many motifs that Melville later used throughout his career, such as the Parisian nightlife and the importance of style in regards to the protagonist, which in the film is Roger Duchesne.

The film is just as much about plot, as it is about the character of Bob. It has all the ingredients of a heist film, the thrills, the stakes, the repercussions, the dame (Isabelle Corey). But what stands out is Bob, how utterly cool he is, and most of the time, how cool and stylish this film we’re watching is.

6. Taking of Pelham One Two Three (Joseph Sargent, 1974)

A simple yet rewarding story: four armed men hijack a subway car and demand a ransom of $1 million for the passengers. Having most of the film set in the subway car creates an unbelievable amount of tension, similar to that of the speeding city bus in Speed. Like Rififi, the film forces the audience to play lookout with its cleverly constructed storyline and 70’s roughness.

A gritty violence and 70s New York complement each other like peanut butter and jelly, and this film is definitely one of the top to celebrate that relationship. The film is sleazy and rough edged. It gives a porthole view of the criminal underbelly of New York. The film was a huge influence on future filmmakers and films, famously for Tarantino, who took the color-coded nicknames for the criminals and used it in Reservoir Dogs. The film’s cast is one of the reasons the film is held at such a high regard. It includes Robert Shaw as “blue”, Martin Balsam as “Green”, Hector Elizondo as “grey”, Earl Hindman as “brown”, and of course…Walter Matthau, in a career best performance as the determined cop ready to take them down, “Lt. Garber”.

5. Reservoir Dogs (Quentin Tarantino, 1992)

A simple jewellery heist goes wrong, leading the surviving criminals to suspect that one of them is a police informant. There’s not much one can say about Reservoir Dogs that hasn’t already been said. Tarantino initially wrote the script to shoot on a much lower budget using 16mm black and white film after getting a hold of some money after selling True Romance. When looking at a “heist” section in the video store he worked in, Video Archives, Tarantino held the genre films in such high regard and was surprised there had been a pause in heist films.

Drawing from previous heist films like Kubrick’s The Killing and Sargent’s The Taking of Pelham One Two Three, Tarantino crafted his own genre film, one where you never actually see the heist. Although a decision purely made for budget reasons, it’s one of the most significant aspects of the film. The witty dialogue, pop culture references and unapologetic violence is what catapulted Tarantino into fame, but it was fully understanding the genre and how to deconstruct it, that made Reservoir Dogs special.

4. Heat (Michael Mann, 1995)

Al Pacino stars alongside Robert De Niro in Michael Mann’s heist epic. Jaded but determined L.A.P.D detective Hanna (Pacino), hunts down the highly intelligent and detail-oriented professional criminal, Neil (De Niro), before he retires for good and forever disappears after his big score. Mann wrote the script in 1979 with the original setting being in Chicago. The script was used for a TV pilot made by Mann and was released in 1989 as a TV film called L.A Takedown. Since the pilot didn’t receive a series order, in 1994, Mann revisited the script and the rest is history.

The film is notable for having two of the most famous and critically acclaimed actors working not only side by side, but against each other. Pacino and De Niro had a very similar career leading up to that point. They both emerged from the famous New York school, the Actor’s Studio, breaking through into fame in the early 70’s with great meaningful roles that shared certain similarities. They were even in the same film, The Godfather Part II, without their characters ever sharing a scene.

But even with Heat, De Niro and Pacino don’t share many scenes with each other until the midpoint of the film, where set in a late-night diner, the two Hollywood legends deliver one of the best scenes ever made.

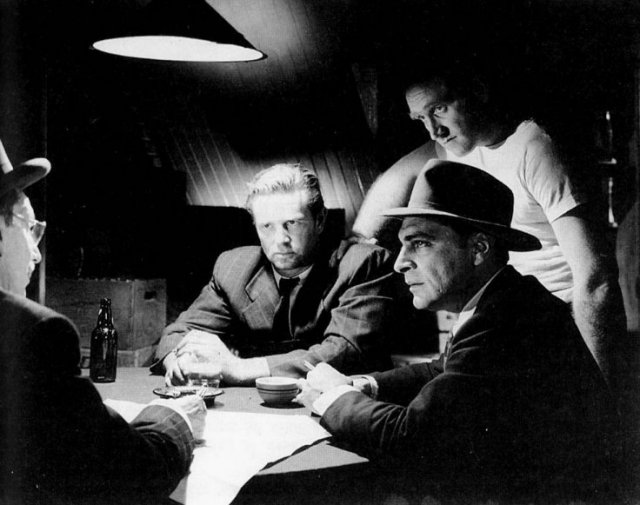

3. The Killing (Stanley Kubrick, 1956)

“In All Its Fury and Violence…Like No Other Picture Since Scarface and Little Caesar!” reads the tagline for Stanley Kubrick’s The Killing. The heist thriller tells the story of crook, Johnny Clay (Sterling Hayden), who gathers a team of five men to rob a race track.

Although far different to his later works, you can see that Kubrick was on his way to finding his style through the film’s camerawork. The film’s low-budget helps give the film a rough, desperate feel, which mirrors what most characters begin to feel throughout the film. Although not breaking any banks at the box office, Peter Bogdanovich wrote in The New York Times that although the film didn’t make any money, it established “Kubrick’s reputation as a budding genius among critics and studio executives” alongside his other film, Paths of Glory.

2. Rififi (Jules Dassin, 1955)

Perhaps one of the more intriguing heist films ever made, Jules Dassin directs this classic heist film that was even banned in Finland upon its release, due to its infamous yet iconic silent heist scene, which authorities stated “taught people how to commit burglary”. The scene is a masterclass in how to create tension and suspense without having characters ever saying a word. The nail-biting scene runs for about 32 minutes and has absolutely not non-diegetic sound, music or dialogue. It puts the audience in the very same paranoid place that the thieves are in, making them the “lookout” for any noise, problem or decoy.

The film was critically praised by future director François Truffaut and film critic Andre Bazin, both praising the blacklisted director for creating such a dazzling and near perfect piece of cinema from an underwhelming novel, written by Auguste Le Breton.

1. Asphalt Jungle (John Huston, 1950)

One of the earliest examples of how great a heist film can be, John Huston’s classic crime thriller has influenced filmmakers and films massively since its 1950 release. Ex con, Dix Handley (Sterling Hayden) plans to steal $1 million in jewels and gathers a team of crooks, including a lawyer (Louis Calhern) and a safecracker (Anthony Caruso). The heist seems like a success until a stray bullet tragically kills one of the men. Scrambling to pick up the pieces, greed and selfishness takes over the men which tangles them in a journey of treachery, deceit and murder.

The film is beautifully shot by Harold Rosson, who worked on classic Hollywood masterpieces such as Singing in the Rain, Duel in the Sun, El Dorado and of course, The Wizard of Oz. Rosson uses empty space to isolate the characters during their lowest points, yet remains true to its film-world, photographing the film using classic film noir styles. The film’s supporting cast also solidifies the film as not only good, but exceptional, such as an early Marilyn Monroe, James Whitmore, Jean Hagen, Brad Dexter and many more.