5. Terms of Endearment (1983)

The great Shirley MacLaine completed a stunning career revival when she won an Oscar for Best Actress 25 years after her first nomination for her knockout performance in this bittersweet romantic drama adapted from Larry McMurtry’s 1975 novel of the same name, which takes some time to find its footing but quickly refines itself and builds to a chain reaction of cathartic moments between buttoned-up widow Aurora Greenway, her feisty daughter Emma (Debra Winger), and an eccentric middle-aged neighbor (a horny retired astronaut played with a great deal of gusto and dashes of levity by Jack Nicholson, who also won an Oscar for his role).

A modern perspective might consider certain aspects of “Terms of Endearment” a bit dated or even emotionally manipulative, but CBS stalwart James L. Brooks deserves full credit for drawing great performances out of his ensemble cast and winning five Academy Awards right out of the gate in his first directing effort after having transformed the entire landscape of American television. It isn’t any kind of certified classic, but in fairness, the film did win the Oscar for Best Picture in a historically thin year with no clear frontrunner.

4. Ordinary People (1980)

Astoundingly, Martin Scorsese had to wait until he had a whopping 20 feature-length films under his belt to bag his first-ever Oscar in 2006 for “The Departed”, but he might just as rightly have won for “Raging Bull” 26 years prior, and nobody would have batted an eye. The fact that his 1980 boxing biopic unexpectedly lost the evening’s biggest prize to Robert Redford’s directorial debut is routinely cited by snobbish cinephiles as one of the most glaring examples of the Academy getting it all wrong and overlooking the assumed frontrunner in favor of a safer, duller alternative.

Here’s the thing, though: To unfairly dismiss “Ordinary People” strictly because it doesn’t hold a candle to one of the nominees it went on to beat out on Oscar night would be shortchanging what is, warts and all, a pretty solid Best Picture recipient and, for that matter, a damn good film in its own right.

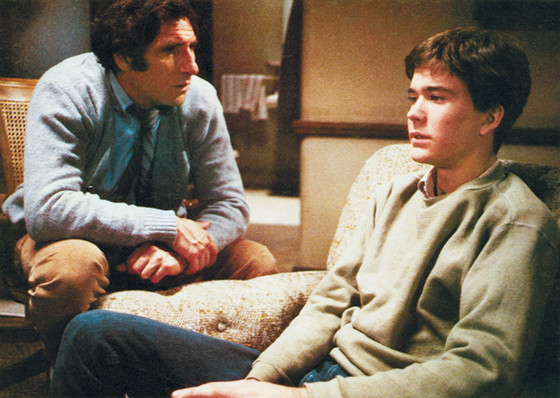

In an industry like Hollywood with a long history of misrepresenting or aggravating the stigma associated with mental disorders, this graceful and startingly compassionate portrait of family strife, starring Timothy Hutton as a grieving and alienated young man reeling off the tragic death of his older brother and Judd Hirsch as his newly-appointed psychiatrist, was not only the exception that proves the rule but a genuine conversation starter that confronted a hot-button topic like depression in frank and unflinching terms where any Hollywood production before would’ve skirted the subject.

3. The Last Emperor (1987)

If there’s a through-line to Bernardo Bertolucci’s career, it’s quixotic ambition and a bone-deep understanding of the corrupting influence of power and greed on the human spirit. In converting the life and times of Emperor Pu Yi, from his coronation as a 3-year-old toddler through his abdication during Japanese rule and meager existence as a peasant worker after the Communists took shop, into a fascinating prism through which to view the broader social changes in 20th-century China, Bertolucci reached new creative heights while working with an even bigger canvas than he did in “1900” after being given free rein to shoot within Beijing’s Forbidden City.

A filmmaker with a keen sense of scope and a career-long obsession with tragic characters who are helplessly swept aside by the tides of history, the Italian-born iconoclast visionary earned widespread acclaim and took home best-directing honors at the 60th Academy Awards ceremony. And yet, despite its impressive 9-Oscar trophy haul, “The Last Emperor” is still not nearly as appreciated as it deserves to be, and it’s disappointing to rarely see it mentioned these days in the same breath as Bertolucci’s other high-water marks like “The Conformist” or “Last Tango in Paris”.

2. Platoon (1986)

Whatever your thoughts on Oliver Stone in the year 2024 (the writer-director once anointed as America’s provocateur par excellence who made an entire career out of sticking to the Man has admittedly lost his edge in recent times), there’s little doubt in our minds that the right movie prevailed when Dustin Hoffman presented this hard-hitting Vietnam War drama with the award for Best Picture at the 59th Academy Awards.

In mining his personal experiences as an infantry soldier who was shipped off to ’Nam in 1967 to delve into the murky morality and devastating psychological effects of a cruel and unjustified armed conflict that saw thousands of innocent men being sent to the slaughterhouse in the name of democracy, Stone was a natural fit to deliver one of the most gut-wrenching anti-war statements ever committed to film as well as the capstone achievement of his prolific career.

Starring Charlie Sheen as an idealistic young recruit who enlists for service in Vietnam only to get caught in a vortex of conflicting loyalties between two bickering Sergeants with opposing moral convictions, “Platoon” would go on to win four Oscars including Best Picture and went down in the history books for featuring one of the most heartbreaking, iconic, and endlessly spoofed death scenes in all American cinema.

1. Amadeus (1984)

The rare case of a movie high both in style and substance, Miloš Forman’s irreverent take on the life and times of Europe’s most celebrated 18th-century composer represents the platonic ideal of what every Best Picture winner should be. Smart, funny, accessible, insightful, and without an ounce of narrative fat, “Amadeus” seamlessly bakes pointed ideas about high society, jealousy, the creative process, the pitfalls of celebrity, and the burden of genius all into its Vienna-set story while taking many artistic liberties in retelling Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s meteoric rise through the unreliable lens of his lesser-known contemporary composer and rumored rival Antonio Salieri (F. Murray Abraham).

Historical accuracy is not the aim here, but the wild digressions and narrative curveballs the film throws at you at every turn is part of what makes “Amadeus” such a singular, chaotic experience and, in retrospect, a far more unconventional choice for Best Picture that people usually give the Academy credit for. Almost every line is a nugget of gold, but the more time that passes, the clearer it becomes that it’s F. Murray Abraham who keeps bringing us back time and time again with a career-defining, Oscar-worthy performance that propels the film even further than its already stellar source material.