6. New York Stories (1989)

A film in three segments, 1989’s New York Stories brings together a trio of legendary directors. With Martin Scorsese, Francis Ford Coppola and Woody Allen being the names on board, it’s clear we are talking about three of the greatest American filmmakers of the past fifty years.

Scorsese’s segment is first, a riveting tale called Life Lessons with Nick Nolte as a fiery painter; the second is a fable of family and loyalty, Life Without Zoe, from Coppola; and the third is Woody’s 40 minute instalment, the brilliant Oedipus Wrecks.

Coming at the back end, Woody’s film stars Woody himself as Sheldon, a New York lawyer constantly irritated by his judgemental mother Sadie (played by the brilliant Mae Questel), but whose life takes a turn for the better when she disappears, seemingly for good, during a botched magic trick by a performing magician. For the first time in his life, Sheldon is happy, content and confident, with every area of his life prospering greatly. However, the dream is over when one day he awakes to see his mother has reappeared, larger than ever, permanently fixed into the New York sky.

New York Stories is vivid, lively and colourful, and a complete feast for filmgoers, though Woody’s film is perhaps the most enjoyable, boasting fine performances from Woody and the great Julie Kavner. Crammed full of genuinely great gags, it’s a treat for Allen fans.

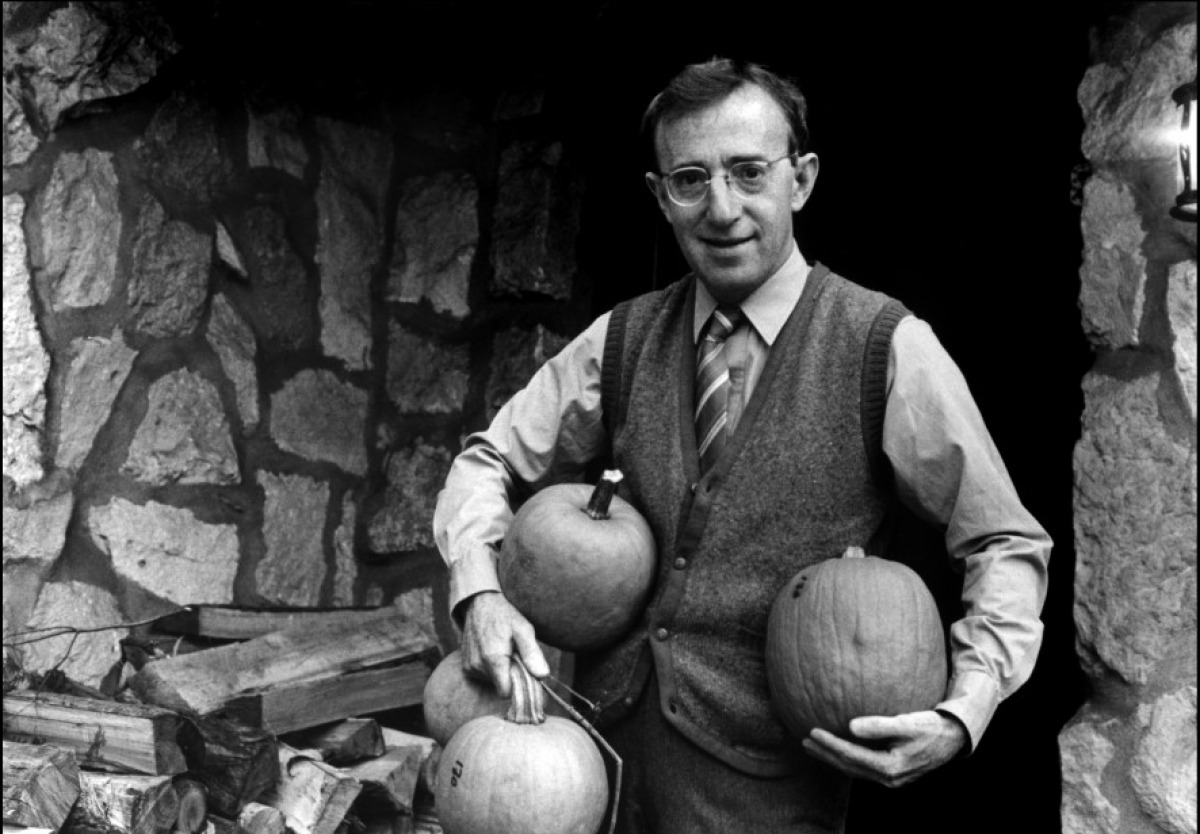

5. Zelig (1983)

Zelig is perhaps the one film where the genius of Woody Allen is at its almighty height. If ever there was a movie to be in awe of, then it’s this, his stunning, challenging and utterly hilarious mockumentary about Leonard Zelig, a shape shifting phenomenon and enigma who seems to take on the form of whoever he is around.

Zelig was made at the same time as A Midsummer Night’s Sex Comedy, and one can see why Woody has not juggled two films at once ever again. He was, quite simply, exhausted. As Midsummer… was much lighter and fluffier, it was more fun for Allen to complete. Zelig however was his most complex picture to date. Featuring then innovative special effects where Woody, as Zelig, was super imposed into actual old reel footage, it was ahead of its time in many ways, paving the way for the likes of Forrest Gump and countless films using the same methods. Gordon Willis and Woody Allen worked painstakingly on perfecting the look, even getting the correct lenses used in news footage from the 20s. To say they pulled it off is an understatement. There have been little bits of special effects in Woody’s pictures before and since, but none of them matched the excellence of the quality in Zelig.

Technicalities aside, Woody made a very clear statement about how a person will bend their beliefs, mannerisms, humour and whole being just to belong and fit into a group. Worse, Zelig not only does it physically and in his mannerisms, he does it politically too. We are given a detailed psychological analysis of the mysterious Zelig, not only by real academics in the field who plays themselves, but by Mia Farrow as Dr. Eudora Fletcher. Though Woody is the star of the show in every way, Mia does well too, and though she is often quite understated in many of his films, she lends herself excellently here.

In every way Zelig is an odd ball masterpiece that sticks out in Allen’s filmography, from the acting, the superb effects, the message it sends and each masterful detail. And let’s face it, we all know a real life Zelig or two.

4. Broadway Danny Rose (1984)

Anyone going through Woody’s career and being a little perplexed, challenged even, by the strange otherworldliness of Zelig, would find themselves eased somewhat by his next picture, the wonderful and hilariously funny Broadway Danny Rose. Like an old friend coming round for tea, we get the full on neurotic, cowardly, bumbling Woody. Danny Rose (Allen) is a slightly pathetic show business agent with a whole roster of questionable acts. The film begins with a bunch of veteran comic discussing the mythical Danny Rose round a table, and the subsequent plot concerns Woody’s third rate singing act Lou Canova (Nick Apollo Forte) having an affair with gangster’s moll Tina (Mia Farrow). When Danny is mistaken for Tina’s boyfriend, her mobster ex becomes enraged with jealousy and orders for Danny’s execution. What follows is one of Woody’s finest farcical set ups, with gag after gag hitting the spot.

Broadway Danny Rose is light but still cleverly structured, and the fact that the story is told through flashback by the old gossiping comedians is pure genius. Woody is at his best here, pathetic but appealing as ever. Mia Farrow is excellent too, perhaps her finest performance in a Woody Allen movie. Woody had written the part just for her, based on a woman they had met, and the decision to have her wear sunglasses made her character all the more cool and slightly aloof. She acts as a perfect comedic spring board for Woody; she stays calm, yet he repeatedly becomes increasingly irate and stressed.

As usual, the film looks glorious. The black and white cinematography is beautiful too, but for once New York is not clearly visible as the New York Woody usually presents us. This could be anywhere in the US, soulless almost, with its creepy warehouses and anonymous streets making the film more universally relatable.

3. Hannah and Her Sisters (1986)

We are back in iconic New York territory, and the land of neurosis, complex relations and upper middle class worries in Hannah and Her Sisters, Woody’s remarkable Oscar winning comic drama. The film started a new era in Woody’s career, that of the more strictly defined drama with comic elements, preoccupied with the world of playwrights, poets, doctors, architects, TV writers and respectable people with perplexing dilemmas.

Though there were quite a few A listers in Hannah and Her Sisters, it was by no stretch a star picture. A complex, wonderfully woven story with rich, believable characters and a brisk pace, Hannah and Her Sisters, in many ways, set the way for many of Allen’s follow up pictures. Famous faces working for low pay, for the sake of the art, utterly devoted to the Woody Allen vision. The focus shifts to the upper middle classes and even the upper classes. This is the world he knows, the kind of people he meets, the conversations they have and situations they face. The unremarkable is made remarkable in the Allen universe.

Like Interiors, it focuses in on a group of strong women, sisters once again, all of whom are very different in many ways. Mia Farrow is Hannah, the strongest of the sisters and the one who seems to be holding it all together. Michael Caine stars as Elliot, her husband, who is falling in love with Hannah’s sister Lee (Barbara Hershey), herself seeing an older man, the artist Frederick (the great Max Von Sydow). Woody plays Hannah’s ex husband, Mickey, a TV writer who is also a panicking alarmist who dreams up different diseases and health issues. Dianne Wiest is Holly, the more troubled of the three sisters, who has recovered from drug problems and runs a business with her friend April (the late great Carrie Fisher). Set in a two year period, the film weaves in and out of the various stories, as romance develops into obsession. In the end, despite the various troubles, things end up pretty okay for everybody.

Hannah and Her Sisters is another (pretty much) perfect film for Woody, in that all the elements quite simply come together to create something quietly magical. The performances for one are some of the finest in Woody’s canon. Michael Caine gives one of his top five efforts in an Oscar winning role. It’s a part you wouldn’t have necessarily associated with Caine before this, but it’s a performance so strong that it’s hard to imagine anyone else in his place. The great Dianne Wiest also nabbed as Oscar for her work, a much deserved one too I might add. Structurally, the film has a beautiful novelistic form to it, and it’s carefully edited to enhance this approach.

The privileged, the bourgeois, the complacent and the self absorbed, they’re all here, their dilemmas made all the more meaningless by the grim spectre of Death overseeing it all.

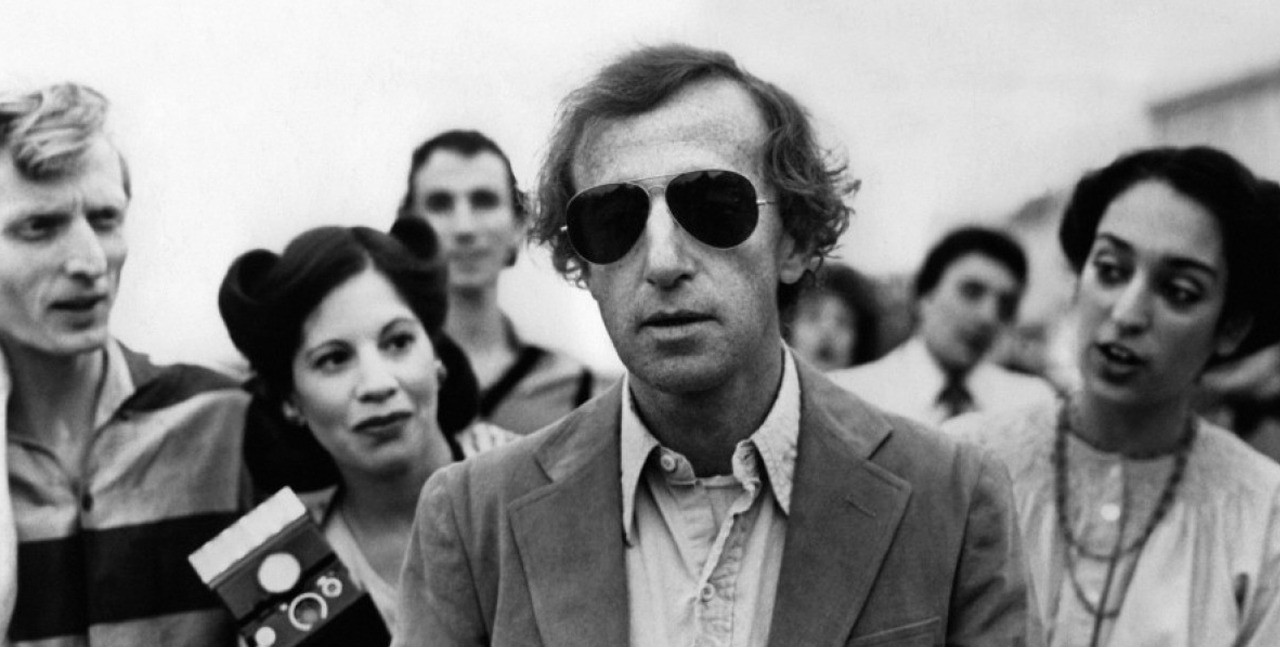

2. Stardust Memories (1980)

Woody’s infamous Stardust Memories was often said to be his most difficult, destructive and uncommercial picture, the one where he turned his back on the audiences he had supposedly built up with Annie Hall and Manhattan. Here was another black and white tale of self doubt, this one featuring Woody as a film director who questions himself, his past and loves while attending a film festival in his own head celebrating his work.

Criticisers of the movie assumed he was turning up his nose to the punters who loved his early comedies but thought he had wasted away his comedic gift by turning to more artistic pictures. According to his latest work then, if it were to be taken as the truth, the fans and admirers were little more than a sea of smiling, fawning faces standing in his path towards the alluring exit of celebrity-ville. Of course, that’s the way you see it when you take Woody’s movies too literally, and foolishly believe that all his work is totally autobiographical.

Reaction to the film was hostile and negative upon release, but it remains a firm favourite of Woody’s. All these years on, perhaps with viewers separating Woody from the film’s lead character, Stardust Memories has become another entry in the more downbeat and brilliant side of Allen’s canon. OK, so it isn’t your poster child for New York, or the ultimate rom-com, but it is a complex, deep and fascinating study of egotistical self importance. It’s also funny, only the jokes don’t just come thick, fast and in your face. They kind of creep up, give you a nudge in the ribs, and only later may you realise how good they were. And that pretty much goes for the whole film too.

1. Crimes and Misdemeanors (1989)

Woody finished off a mixed decade with a masterpiece very much his own, the wonderful Crimes and Misdemeanors. While Manhattan had perhaps represented the peak of his talent in the classic 70s era, this powerful 1989 comedy drama is arguably the zenith of the mid Allen period. What makes it so essential and important is in the way it combines all the important subjects so key to Woody’s work, and puts them into a very digestible, engaging and highly entertaining 100 minutes. Death, love, jealousy, envy, religion… it’s all here.

Crimes and Misdemeanors juggles two stories. The first involves respected ophthalmologist Judah (Martin Landau), a family man whose sordid affair with Dolores (Anjelica Huston) is threatening to ruin his cosy upper middle class existence. He turns to two people for advice; the spiritually moral rabbi Ben (Sam Waterson), who is stricken blind but retains his admirable – and enviable as it turns out – faith in god and the goodness of mankind; and his brother Jack (Jerry Obrach), who has ties to the mob.

Judah is presented with two choices, both morally opposed to one another; to confess the affair to his wife before Dolores comes forward, or to have murdered by a hit man. After a surprisingly brief time of consideration, he opts to have her killed. At first the guilt eats him up, but after a while, it eases, and then eventually disappears. In this case, the awful truth is there is no higher power to condemn the man for his sickening sins, and his conscious lets him be. Most disturbing.

The other story concerns Woody as a struggling filmmaker called Cliff, who has been commissioned to shoot a documentary portrait of his pompous, self-important brother in law Lester (Alan Alda), a roaring success in the TV world which Woody’s financially challenged character looks down upon. Cliff’s marriage is on its last legs, and he is falling for another woman, the show’s associate producer Hally (Mia Farrow). While struggling with his integrity – and editing a documentary on an obscure philosopher, his true film passion – he escapes into the world of classic cinema, and it’s when viewing the old reels of Singin’ in the Rain that Cliff looks truly happy.

Crimes and Misdemeanors is one of Woody’s most thought provoking movies, and has you pondering on faith, justice and the human conscience from start to finish. The script raises dichotomies and moral issues throughout; the existence of god, the dual issue of life and death, the divide between reality and fantasy, and the unfairness of life itself. Cliff is quite possibly the only decent character in the movie, save of course the rabbi, who is a deeply honourable man in his own right. Even Hally, who Woody believes to have far too much depth to be sucked in by the ostentatious Lester, is won over by his wealth, success and shallow charisma.

The real underlying theme though, for me at least, is man’s acceptance of himself, learning to live with his sins and in Cliff’s case, his limitations. The winners are those who have their stories heard, and Cliff is this story’s one great Loser. He loses his wife, he loses the film job and he loses the woman he has fallen in love with. Lester has it all, and keeps on earning more despite his monetary and personal wealth. The injustice of it all resonates profoundly.