6. What Dreams May Come (Vincent Ward, 1998)

Sometimes cinema can touch not only the heart but also the soul, especially if it is created with such mastery as Vincent Ward’s film What Dreams May Come. In this incredible story, viewers are immersed in a journey through worlds where the boundaries between reality and imagination are blurred. Ward managed to create a majestic picture, where every frame comes alive on screen. He skillfully transports the viewer to the heaven and hell of the main character Chris Nielsen, played by Robin Williams, creating not just a spectacular landscape, but an emotional journey.

Heaven here is portrayed as the main character’s personal painting, a collection of his tenderest memories and dreams. Hell appears as a chaotic world, embodying fears and losses. The visual composition of these places, combined with a refined screenplay, embodies the idea that life after death can be as varied as life itself. It is amazing how Ward used color and light to create the visual rhythm of the film, where each frame can be considered a work of art. He intertwines real and imagined worlds so that the viewer literally feels every image.

This film does not just satisfy the eye, but also makes one think about the big questions of existence, life, death, and eternal love. It offers a profound and inquisitive look at the human soul and how we perceive the world around us. What Dreams May Come is not only a cultural contribution to cinema but also an everlasting reminder that cinema can be not only entertainment but also a medium for exploring the deepest human emotions and questions. It is indeed a unique film that continues to inspire and astonish with its visual beauty and spiritual depth.

7. In the Mood for Love (Wong Kar-wai, 2000)

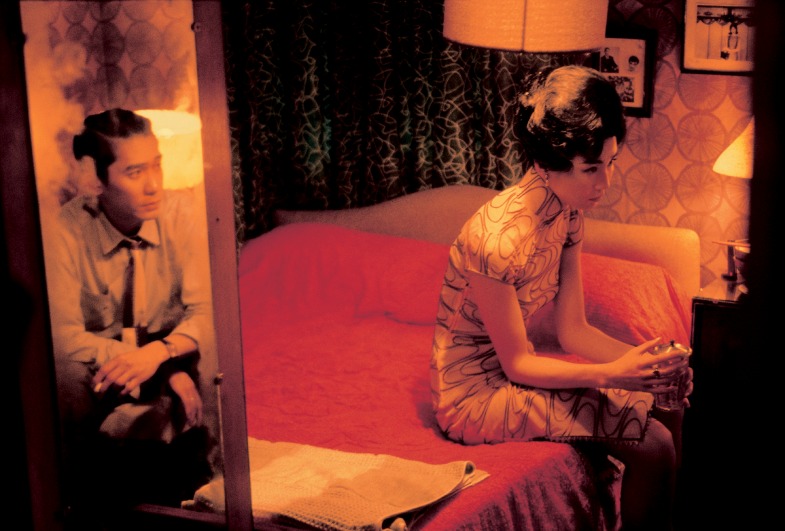

The visual style of In the Mood for Love, directed by Wong Kar-wai, permeates the entire film and stands as one of the greatest achievements of cinematic art in the early 21st century. This film is undoubtedly a triumph of cinematographic artistry. Cinematographer Christopher Doyle, in collaboration with Wong Kar-wai, crafted refined frame compositions, utilizing doorways and corridors to create a sense of intimacy and simultaneous alienation between the characters. Slow-motion cinematography and repeated editing sequences amplify this impression, conjuring a feeling of time that seems to have stopped or looped at specific moments in the characters ’lives.

In every frame, the director’s aspiration to convey the subtle nuances of the characters ’emotions is clear. One of the key elements of this visual splendor is the rich color palette, especially the use of red and gold, which emphasizes the passionate and romantic nature of the narrative. The characters ’costumes complement this visual impression, creating a style and ambiance of the era, as well as reflecting the inner world of the characters. The theme of infidelity in In the Mood for Love becomes an occasion for exploring human relationships and the inner world of the characters.

Wong Kar-wai does not merely tell a story, he allows us to peer into the very depths of the characters ’souls through visual imagery and symbols. This film does not merely satisfy the eye, it penetrates the heart. It exemplifies how visual style can become an integral part of the storytelling, making cinema not merely a means of entertainment but an art form in the truest sense.

8. Amélie (Jean-Pierre Jeunet, 2001)

Amélie, crafted by the talented director Jean-Pierre Jeunet, is a true feast for the eyes, merging sophisticated compositions, the warmth of the color palette, and the wit of visual storytelling. Amélie teaches us to see beauty in the mundane and find poetry in simple things, making this film not only visually stunning but also rich in soul. Combined with a vivid and saturated color palette, where red and green shades dominate, the cinematography ascends to a new level, transforming the ordinary into the magical. These colors become tools for not only aesthetic pleasure but also narrative expressiveness, accentuating the mood and character of the figures.

Special attention in Amélie is given to frame composition: unusual shooting angles, inventive use of focus, and dynamic editing infuse the film with a fairy-tale effect. These cinematographic techniques underline the uniqueness and enchanting beauty of the main heroine’s world, making the commonplace magical. Visual metaphors and symbolism permeate every corner of the film, turning simple objects and details into symbols of profound feelings and truths of life. The interaction of these elements with a rich color scheme creates a cohesive visual language, which has become an important stage in the development of cinematic art.

The specific editing and dynamic rhythm of the scenes add to the impression, injecting energy and playfulness into the narration. Amélie is not merely a cinematic masterpiece, but an important milestone in the art of film, whose visual splendor continues to inspire directors and audiences around the world. This film is a bright example of how a carefully conceived visual concept can enrich the plot and transform cinema into a true art form.

9. The Fall (Tarsem Singh, 2006)

The perspective on cinematic art is upended in Tarsem Singh’s work The Fall, a film that has become an expressive symbol of modern visual narrative. The main plot revolves around the meeting of a paralyzed stuntman and a young migrant girl in a hospital. Their relationship serves as a gateway to a magical world of fairy tales, populated with unusual characters and astonishing places. But it is not just a story within a story. Singh seamlessly intertwines the real world with the fictitious one, creating a remarkable symbiosis of visual and emotional experiences.

Filming in 28 different countries around the world allowed creating scenes of unparalleled beauty, ranging from lush tropical landscapes to picturesque deserts and ancient buildings. This diversity, combined with a creative approach to costumes and decorations, forms a unique visual style. The intricate texture and color palette of these elements enrich the film’s visual language, adding layers of meaning and interpretation. Every frame, every shade, becomes part of a complex narrative that extends beyond words and actions.

Singh builds bridges between reality and fantasy, between the visible and invisible, guiding the viewer on a path where boundaries blur and new horizons are unveiled. The cinematography in The Fall explores new approaches to storytelling through visual art. The camera work, editing, lens, and filter choices make the viewer feel like they are part of that world, experiencing every moment and emotion. The Fall is not just a cinematic work, but a unique exploration of visual perception and cinematic techniques. This film immortalizes the beauty, complexity, and depth of cinematography, making it an essential milestone in the development of the seventh art.

10. The Grand Budapest Hotel (Wes Anderson, 2014)

Imagine a scene where the architecture, costumes, and even the manners of the characters all conform to a unified aesthetic concept. In The Grand Budapest Hotel, every piece of décor, every glance of the characters, contributes to the overall tapestry, creating a refined and harmonious masterpiece.

Anderson transforms a fictional European country into an arena for philosophical contemplations and human dramas. He does this with such ease and grace that the viewer is involuntarily immersed in a world where reality and fantasy merge into one. The harmony of symmetry within frames represents a delicate balance and order. Colors do not merely fill the screen, they animate it, crafting vivid and rich images that complement and reveal the emotional depth of the characters.

Complex decorations and costumes act as an additional language in the film, reflecting cultural and temporal contexts that might otherwise remain invisible. Handcrafted details and miniature special effects embody the soul of craftsmanship, returning us to the roots of cinematography and adding authenticity to every movement. Anderson also employs unique transitions and animation to lend dynamism to the narrative, emphasizing not only the visual aspect but also the rhythm and tempo of the story. These cinematic solutions work together to create not just a beautiful film but a deeply penetrating visual experience.

The main characters, concierge Gustave H and lobby boy Zero, are not merely participants in the events but guides into this magical world. Their relationship is not only a dynamic plot device but a metaphor for cinema itself–a complex and multifaceted art form. Through its visual language, The Grand Budapest Hotel speaks about time and its influence on culture, the relationships between generations, fidelity to traditions, and pursuiting novelty. This is a film about film, where every detail, every symbol, opens a new door into the world of art.

The Grand Budapest Hotel is not just an entertainment project, it is a meditation on art, a poignant and inspiring journey into the very essence of cinema. In Anderson’s hands, the camera becomes the brush of an artist, and the screen–a canvas on which he creates something more timeless than just a cinematic image.