In the wise words of Roger Ebert, no good movie is long enough and no bad movie is short enough. However, it can be difficult to identify which ones truly justify their extended running time with so many blockbusters and studio releases stretching past the three-hour mark these days.

Combing through likely titles for this list, one realizes there are far too many lengthy films in cinema history deserving of your attention, which explains the glaring omission of sprawling epics like “War and Peace”, “Reds”, “Heaven’s Gate”, “Malcolm X”, “The Right Stuff”, “JFK”, “Short Cuts” and “An Elephant Sitting Still”. However, there should be a little something for everybody in this round-up list of three-plus-hour movies, ordered by length in ascending order, that may seem daunting at first glance, but will reward your patience and commitment.

1. Oppenheimer (2023) — 180 minutes

Christopher Nolan struck box-office gold and blew by the competition on his path to Oscar glory for last year’s three-plus-hour biopic starring Cillian Murphy as the titular American physicist who oversaw the development of the atomic bomb near the end of World War II.

A star-studded Hollywood tentpole of epic proportions the likes of which few working directors could realistically pull off in this day and age, “Oppenheimer” earned universal acclaim for its terrific performances, pulsating score, and surgical approach in dissecting the knots of contradictions behind one of the most polarizing figures of the 20th century. But it all plays second fiddle to Nolan’s flashy, muscular direction and keen sense of large-scale spectacle, which ensures the film keeps the audience on its toes from start to finish. It doesn’t all hang together, but good luck trying to pry your eyes away from the screen at any time during its dizzying climax.

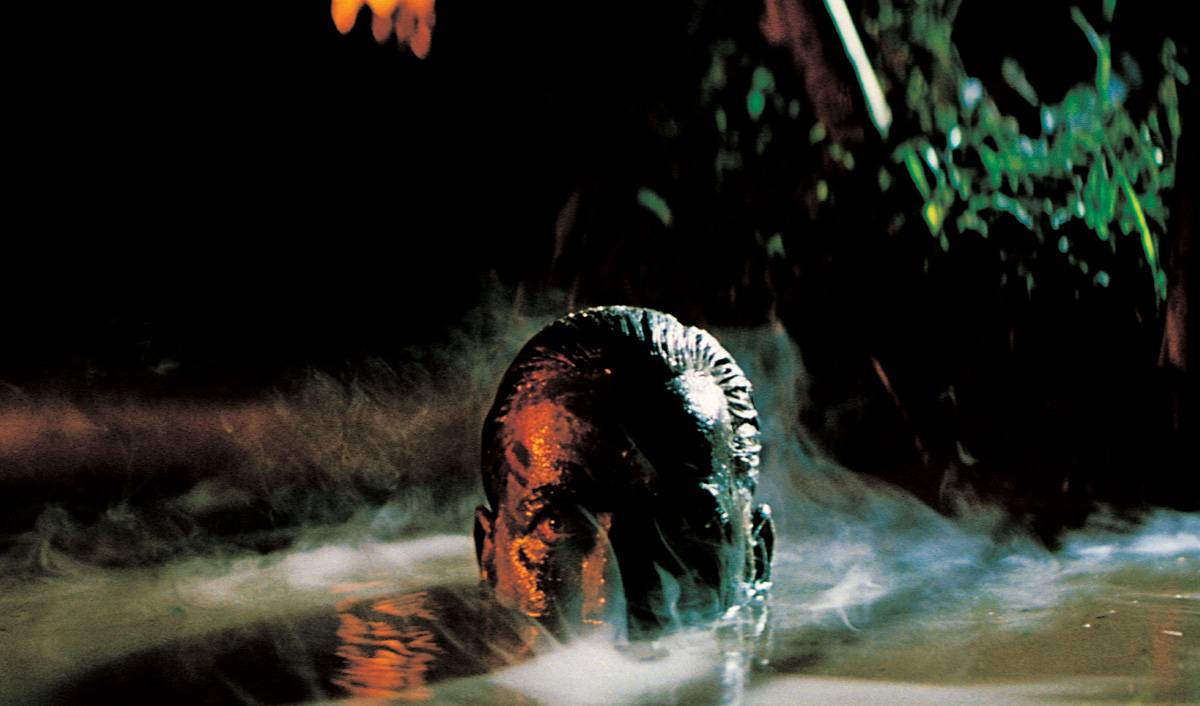

2. Apocalypse Now (1979) — 183 minutes

If Truffaut was really onto something when he suggested in 1973 that every movie that claims to be anti-war ends up glamorizing it, bear in mind that was six years before Francis Ford Coppola ripped open film grammar with his operatic overview of the Vietnam War — a hallucinogenic descent into hell, a place in which innocent men are sent to the slaughterhouse in the name of democracy and helicopters soar through the skies synced to Wagner’s Ride of the Valkyries.

Because we love the smell of napalm in the morning and also because the French plantation scene is not nearly as bad as people make it out to be (seriously, it’s time to get over it!), we’re circumventing the rules by slipping in the 2019 Coppola-approved Final Cut, which just barely stretches “Apocalypse Now” past the three-hour mark. And remember — in a mad world, only the mad are sane.

3. Barry Lyndon (1975) — 185 minutes

A bonafide classic strewn from bits and pieces of an unrealized, decades-in-the-making Napoleon biopic that Stanley Kubrick never managed to get off the ground, this lavish 18th century costume drama sees Ryan O’Neal step into the shoes of penniless Irish rogue Redmond Barry — a shamelessly opportunist social climber whose rise in status after marrying into a wealthy noble family is ultimately undone by a string of cruel twists of fate.

Widely considered a flop upon its initial release, “Barry Lyndon” has slowly been reappraised by critics, with many declaring it a display of stunning visual artistry that is now a frequent contender for the “best looking film of all time” crown. Make no mistake, though: This rags-to-riches epic is much more than a collection of pretty frames that look as though borrowed from Renaissance paintings, in fact, depending on who you ask, it might just well be Kubrick’s best.

4. The Leopard (1963) — 185 minutes

Luchino Visconti blew through the ’60s decade on a creative high, following up his piercing working-class parable “Rocco and His Brothers” with the Palme d’Or-winning “Il Gattopardo”, a sumptuous 19th-century family drama tinged with melancholy that observes the slow but steady decline of the Italian nobility during the Risorgimento at a personal, intimate scale.

Anchored by many recognizable faces such as Burt Lancaster, Alain Delon, and Claudia Cardinale, “The Leopard” vividly traces the tumultuous political shifts ignited by Garibaldi’s insurrection through the perspective of aging Sicilian prince Don Fabrizio Corbera. As the long-held natural order collapses on itself, so does his aristocratic family’s once-assured old social strata. One of Martin Scorsese’s all-time favorite movies, the influence of this opulent 185-minute drama composed by Nino Rota can be felt everywhere from “The Godfather” and “The Age of Innocence” to “The Favourite”.

5. Magnolia (1999) — 189 minutes

With his third movie, Paul Thomas Anderson cashed in his chips and let all his quirks run rampant: the classic San Fernando Valley setting, multiple interlocking storylines, dysfunctional father-child relationships, frenetic editing, wall-to-wall needle drops… The fact that every element in “Magnolia” is cranked up to eleven works both for and against it, but ultimately only enhances the deeply felt heart-to-heart moments shared between its characters.

Starring a murderers’ row of capital-G Great actors including a career-best Tom Cruise as an Andrew Tate-type pickup artist, this humanistic urban mosaic whips by at such a clip you’ll find yourself catching your breath by the time frogs (literally) start falling from the sky. Make no mistake, though — in today’s cinematic landscape where self-deflating irony has become hard currency, Anderson’s earnest sentimentality and go-for-broke showmanship is an endearing feature, not a bug.

6. Schindler’s List (1993) — 195 minutes

Though his credentials as a generational crowd-pleaser were never in question, the early rap on Steven Spielberg was that he was a populist entertainer whose films always sold like gangbusters but lacked the strong authorial stamp and delicacy of touch of the Scorseses and Coppolas of his generation.

As silly as those accusations may seem with thirty years of hindsight, the director would set the record straight in 1993 by helming the greatest one-two punch in cinema history: an era-defining box-office hit (“Jurassic Park”) followed by a 7-time Academy Award-winning prestige drama (“Schindler’s List”). The latter, a soul-stirring Holocaust tale of a real-life Nazi industrialist (Liam Neeson) who saved over a thousand of lives by employing Polish-Jewish in his factories, continues to be a guidepost for how to create a great movie about the human condition in the face of unfathomable tragedy.

7. The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King (2003) — 201 minutes

Whatever the time, whatever the season (but especially around Christmas), it’s never wrong to take another trip to Middle-Earth and revisit Peter Jackson’s sprawling adaptation of J.R.R. Tolkien’s fantasy novels.

It may feel like splitting hairs, but there’s a real argument to be made for the third and final installment in the trilogy as the strongest overall. Winner of an unprecedented 11 Academy Awards, this 201-minute epic draws its primary weight in tying up every loose end in the story and delivering a satisfying send-off to our heroes: Frodo and Sam arrive to Mount Doom to destroy the One Ring, Aragorn embraces his destiny as the true heir to the throne of Gondor, and Sauron’s dark reign is finally brought to an end. By the time the fourth or fifth climax rolls in, it doesn’t feel like excessive payoff but the icing on the cake.

8. The Godfather Part II (1974) — 202 minutes

There’s not much else to be said about the Italian-American crime saga that would single-handedly legitimize the mafia subgenre, seal Francis Ford Coppola’s place as one of Hollywood’s preeminent auteurs, catapult Al Pacino into stardom, immortalize the Corleone-in-charge into an enduring paragon of old-school masculinity, and establish the blueprint for spiritual cousins like “Goodfellas” and “The Sopranos”.

Captivating from first frame to last, the sequel not only expands upon its predecessor but retroactively imbues it with added depth, cutting back and forth between Vito’s ascent as a young immigrant vying for power and the moral decay of his alienated son, who struggles to step into his father’s shoes as the new head of the family. If Coppola’s cracked-mirror vision of the American Dream runs the risk of feeling archetypical by today’s standards, it’s only because it codified all of these tropes in the first place after having so thoroughly infiltrated the cultural vernacular for the past half century.

9. Jeanne Dielman, 23, Quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975) — 202 minutes

It’s no backhanded compliment to say that the greatest movie according to the last edition of the Sight & Sound decennial poll turns boringness on its head. As a matter of fact, the infamously unhurried pace of “Jeanne Dielman” is actually not a bug, but a deliberate choice.

In rigorously detailing the mundane domestic chores of a middle-aged Belgian housewife, avant-garde director Chantal Akerman delivered the ne plus ultra of slow cinema as well as a bracingly compassionate feminist manifesto that makes the viewer feel every minute of dull repetition and quiet despair experienced by the titular character — turning the story of a single mother’s pent-up frustration into the story of every woman who’s ever been taken for granted in their life. At just under three and a half hours, this study of stasis might turn certain viewers off in its enormous spareness, but it’s an experience worth clearing your schedule for.

10. Andrei Rublev (1966) — 205 minutes

If a 205-minute black-and-white historical drama about a medieval Russian icon painter going through an existential crisis sounds a bit intimidating on paper, rest assured — Andrei Tarkovsky may have cultivated a rep for being one of the most forbidding arthouse auteurs, but his longest narrative, clocking in at the 205-minute mark, is by far his most approachable.

Soviet authorities deemed “Andrei Rublev” too experimental, esoteric, and anti‐Stalinist for their taste, banning it for domestic release and yanking it from the Cannes Film Festival at the very last minute. In testing the limits of what state censorship permitted at the time, Tarkovsky orchestrated one of cinema’s greatest statements about about faith, religion, and art. Every passage, from Pagan rituals to Tatar invasions, feels astoundingly transportive; like a wormhole that somehow slithered into our present time to transport us back into the Middle Ages.