If you are serious about your love for cinema, you have got to know your essentials so it would be nice to compile a list of ten undisputed masterpieces from ten different nations. If you are a real cinema aficionado, you might have already seen all of these but maybe there are few that are still on your list of shame (i.e. classics you have missed). If you are a new lover of the art of film and haven’t seen all that much yet, these ten films are a great starting point.

It is of course impossible to be even remotely comprehensive when compiling such a list as many of these nations have produced a plethora of classic films and there are nations, which haven’t even been mentioned because we chose to stick to only ten. But for what it’s worth, you simply cannot go wrong with any of these ten movies and anybody with a serious passion for cinema would be advised to see all of them. At some point. Note: movies on this list are ranked in no particular order.

1. Germany – M (Fritz Lang – 1931)

Fritz Lang’s first feature with sound, which he wrote with his wife Thea von Harbou, is an early example of a technically accomplished sound film and became a worldwide hit. The film was one of Lang’s last films in Germany before he departed to the United States in 1933 after having been offered to direct Nazi propaganda films by Josef Goebbles, who was unaware of his Jewish heritage.

The movie tells the story of a mentally ill child murderer, played by Peter Lorre in a magnificent breakthrough performance, who in 1930s Berlin is eluding police as they round up every criminal in the city they can find. This causes the Berlin underworld considerable grief and they decide to form their own hunting parties and when the killer is discovered, a young man manages to mark Lorre with a white chalk letter “M” (for Murderer) on the back of his coat. When Lorre is eventually caught, he is taken to a kangaroo court, where the Berlin underworld puts him on trial whilst the police is closing in.

Shot in expressive black and white, which manages to create a sinister nightly world with deep dark shadows in combination with remarkably fluid camera movement, the film also features fantastic use of sound; the killer is characterised by the tune he whistles and the murder of a child is not shown directly but suggested by a mother’s desperate cries and images of the child’s ball and balloon left abandoned.

The film also has an almost documentary-type feel as it meticulously details the police’s procedures (using the then new techniques of fingerprinting and handwriting analysis). Also, there is an absence of non-diegetic music and some parts were actually played by real-life criminals for authenticity.

M is an undisputed masterpiece and Lorre’s monologue towards the end of the movie, as he pleads for his life in front of the kangaroo court, is simply one of the best monologues ever put on film. As well as being a film that bridges the silent era to the sound era of film, M’s German expressionism verges towards elements of Film Noir (Fritz Lang would go on to make a few Film Noir classics in the U.S. later on). M is a towering achievement and a must-see for any serious film buff.

2. Italy – The Bicycle Thieves (Vittorio De Sica – 1948)

Arguably the best Italian neorealist film ever made and certainly one in the upper echelon of world cinema, The Bicycle Thieves is a classic in the truest sense of the word. Italian neorealism was a post WWII film movement, which used location shooting, non-professional actors and dealt with the hard economic conditions of the working class during this time.

A poor family man, at the end of his tether, finally finds a job putting up posters in the days immediately after the end of World War II. The job, however, requires a bicycle and as the family have nothing of value left, they decide to pawn their bed sheets in order to be able to buy a bicycle. On the first day of the job, the bicycle is stolen which starts a frantic search by the father and his young son through the streets of Rome, attempting to find their sole means of survival.

The film works on many levels: as a document of its era, as a sentimental drama, as clear social commentary and as a prime example of the neorealist movement; which was born out of necessity in post-WWII in Italy as there were simply no means to make movies. Filmmakers were forced to tell simple stories dealing with the after-effects of the war on ordinary poor people, whilst shooting on location and with non-professional actors. This movie received the Oscar for Best Foreign Film seven years before they officially came up with that category; it’s that good!

3. India – The Music Room (Satyajit Ray – 1958)

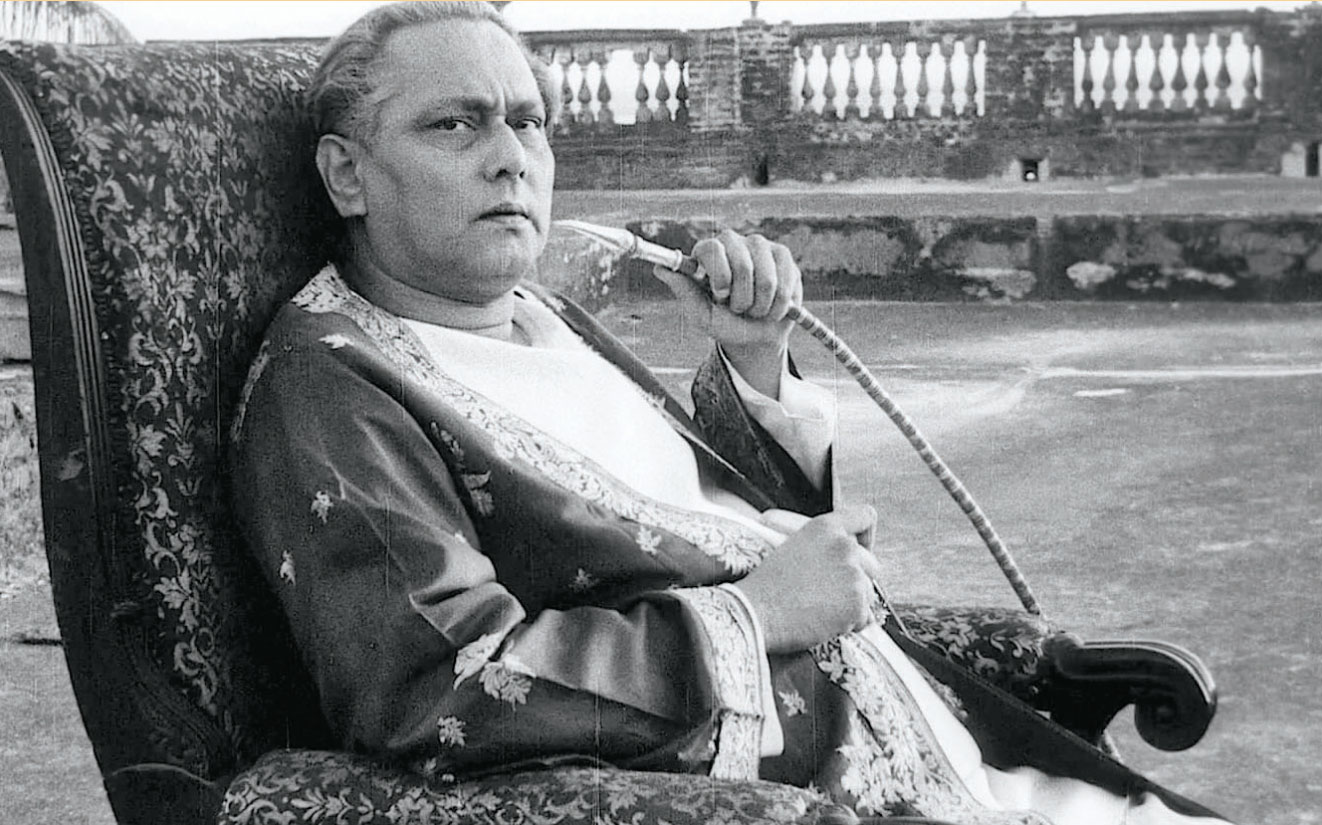

Satyajit Ray, India’s most celebrated director, was at the height of his game in the late fifties. After he made the first two entries in his renowned Apu Trilogy, he managed to find the time to direct The Music Room before finishing his trilogy in 1959.

The Music Room was a failure upon its initial release but it has since taken its place amongst Ray’s greatest works. Whilst the Apu Trilogy might be his best known and most critically praised work, I decided to select The Music Room for this list as it is a stand-alone film and is just as good as any of the films in the Apu Trilogy.

It tells the story of Huzur Biswambhar Roy (Chhabi Biswas), a middle-aged aristocrat in India. Huzur’s fortunes are waning but he holds on to his pride and tries to maintain his social status and heritage by throwing lavish music parties in his mansion’s music room, even though he cannot afford them. His wife tries to keep him from spending their last resources but Huzur doesn’t listen and spends huge amounts of money on a party for their son who is coming of age. Then tragedy strikes and Huzur goes into deep depression until a shrill social-climber tries to outdo him and he decides to give one last grand party in his music room.

The film initially received poor reviews in India but when it was released in the West, it was met with critical acclaim and financial success. The first film to extensively use Indian classical music and dancing, the film features a number of truly memorable performances by some of India’s top musicians at the time.

A stunning drama with a marvellous performance by Chhabi Biswas, who manages to make an extremely arrogant and foolhardy man remain sympathetic throughout the entire film, and an analogy for a class which was disappearing from India, The Music Room is certified classic cinema and just as stunning as Ray’s celebrated Apu Trilogy.

4. France – La Grande Illusion (Jean Renoir – 1937)

One of the best war movies (or like all great war movies, an anti-war movie) ever made, La Grande Illusion is a humanistic masterpiece of poetic realism.

The story deals with two French men, one an aristocrat called de Boeldieu (Pierre Fresnay), the other a working class man called Maréchal (Jean Gabin), whose plane is shot down by German aristocratic aviator von Rauffenstein (Erich von Stroheim) during World War I.

They survive and are invited for lunch by von Rauffenstein, who discovers he shares mutual acquaintances with the French aristocrat; a clear sign that these men might have more in common than they differ from each other. Both men are then transported to a POW camp where amongst others, they meet a French Jew called Rosenthal who generously shares his food rations with others. They make various plans to escape but just before they finish an escape tunnel, everybody is transported to another camp.

The men are moved to a few different camps and finally end up at Wintersborn; a mountain fortress prison commanded by Von Rauffenstein. During the time of incarceration, the two aristocrats from different nations almost become friends until Boeldieu acts as a distraction in order to let his friends escape, and von Rauffenstein is forced to shoot him. He regrets this greatly and as he nurses de Boeldieu during his last hours, the men mourn the disappearance of their class, which the war will bring about. Meanwhile, Maréchal and Rosenthal travel across Germany trying to reach safety until they finally reach Switzerland.

The title of the film was taken from the book The Great Illusion by economist Norman Angell, who argued that war was futile because of the common economic interests of all European nations. The film examines the absurdity of war, the decline of aristocracy across Europe and the bond of humanity which we all share. It has been said that Renoir specifically created the character of the Jewish Rosenthal as a symbol of humanity across class lines and to also counter the rise of anti-Semitism in Hitler’s Germany.

La Grande Illusion received a “Best Artistic Ensemble” prize at the 1937 Venice Film Festival despite being banned in Italy and Germany. However, the greatest acknowledgement of its potent message was that Joseph Goebbels declared the movie: “Cinematic Public Enemy No. 1” and ordered all prints to be destroyed. One of the greatest films ever made and an absolute must-see for all lovers of cinema.

5. Japan – Tokyo Story (Yasujirô Ozu – 1953)

Tokyo Story is often seen as the crowning achievement of Japanese director Yasujirô Ozu’s oeuvre, a body of work which is littered with masterpieces anyway.

The story is deceptively simple: an elderly couple travels from their village to Tokyo to visit their children who live and work in the capital. Once there, it becomes obvious that their eldest son and daughter don’t have time for them as they are too busy with their respective jobs.

The only person who actually takes time out for them is their widowed daughter-in-law, who treats them kindly and shows them the sights of the big city. Their older children arrange a visit to the Atami Hot Springs for their parents but they feel like they are just being kept out of the way and soon return to Tokyo disappointed. They decide to go back to their village but during the trip back the elderly mother gets gravely ill and it might be too late for their children to make amends.

A story about modern urbanization and changing values in Japan after the war, Tokyo Story is a truly beautiful film in which the director, in his trademark style, focuses on the little details, often keeping the camera running after the actors have already left the frame.

This quiet and silent approach, in combination with the static low-angle framing and the languid pace of the movie, have an almost meditative effect and the film gracefully depicts the relentless passing of time and man’s inevitable fate.

A true masterpiece of cinema, Tokyo Story often rightfully shows up in polls as one of the best films ever made. A film everybody should see at least once in their lives.