Austrian film director and screenwriter, Michael Haneke is one of Europe’s most prominent and controversial auteurs working today. He began his career in television and theatre and it wasn’t until late in his career at the age of 33 that he began working in film, with his 1989 cinematic debut Der siebente Kontinent [The Seventh Continent]. From then on his films have gained much praise and international recognition.

Common themes in Haneke’s dystopian works include discontentment and estrangement experienced by individuals in modern society – namely the European bourgeoisie, the personal suffering and increased disconnection experienced by humankind and the inherent cruelty and violence lying under the surface of modernity. His films are provocative and complex challenges to his audience and rely heavily on his interest in psychology, philosophy, spectatorship, semiotics and violence in the media.

Some of Haneke’s biggest cinematic influences include such European greats as Alfred Hitchcock, Andrei Tarkovsy, Michelangelo Antonioni, Robert Bresson, and Krzysztof Kieslowski and it is clear to see their influences on his visual and narrative style.

Haneke is a provocative yet cerebral filmmaker who believes that cinema’s most important function is to disturb and disorient its viewers, assaulting them out of their habitually passive ways of perceiving reality.

The master of enigmatic endings, Haneke is much more interested in “raising questions rather than giving answers”. Haneke’s films are often existential and as such do not provide easy answers, which allow his audience to form their own opinions and question their own perceptions and provide a means of self-reflection.

10. Le Temps Du Loup [Time of the Wolf] (2003)

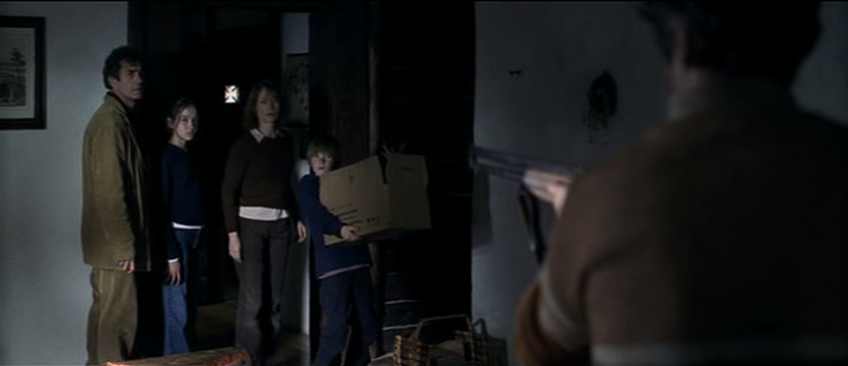

In Haneke’s sombre drama, in the aftermath of a catastrophic global disaster, the Laurent family; mother Anna (Isabelle Huppert), father Georges (Daniel Duval) and their two young children, retreat to the presumed safety of their holiday home in the French countryside. Upon their arrival they discover their home has been invaded by another desperate family.

In an unexpected and violent act Georges is brutally killed and the family are left to fend for themselves in a nightmarish apocalyptic landscape. After finding a group of survivors, the family has hopes for salvation, but in this barren land where social order has been destroyed and tensions run high, there is ultimately no faith left.

This film is enigmatic in its entirety – with no explanation given for the disaster that has affected these people or resolution to their plight. Although the film includes violence, we are not shown any bloodletting, except for a scene of real horse slaughter, which although was filmed under human conditions, caused great controversy.

Haneke shoots the film with attention to realism, using only natural light sources and a gloomy and darkened color palette to reflect the grim, desolate landscape. Le Temps Du Loup is a challenging film which questions the morality and brutality of human kind in a world with no social order.

9. Code Inconnu [Code Unknown] (2000)

Like Haneke’s previous 71 Fragmente, this cryptic and elusive film follows the intersecting lives of a group of Parisians representing differing social cultural and economic backgrounds.

We are introduced to actress Anna (Juliette Binoche) and her war-photographer boyfriend Georges, his brother Jean who has run away from home and their father who is struggling to keep his emotions suppressed while running his farm.

Other characters include African immigrant Amadou who teaches music to deaf children and his taxi driver father and Maria, a Romanian immigrant who is deported from France for begging. The lives of these characters have no real narrative importance or resolution – the film it is merely a glimpse into their everyday existence.

Despite the ubiquitous narrative, there are clear themes of the lack of communication in our Western and ever-expanding multicultural society, racism, war, poverty and love.

Code Inconnu is arguably Haneke’s most challenging and repeat viewings are necessary to grasp the film’s complex messages but like life itself, this film provides no easy answers, but asks some fascinating questions about the human condition and our interactions in modern world.

8. 71 Fragmente einer Chronologie des Zufalls [71 Fragments of a Chronology of Chance] (1994)

This film is the third in Haneke’s Glaciation trilogy focusing on the violence and alienation of the bourgeoisie. This experimental collage film by Haneke is comprised of 71 scenes which follow the lives of several people in Vienna over the course of a year; they include a homeless Romanian boy, a bank security officer, a childless couple, a frustrated student, and an old man. This non-linear narrative culminates in a violent bank shooting involving these seemingly un-connected characters.

71 Frangmente is a slow-burn mystery in which each narrative puzzle-piece fits together to form a whole film. Like a great Hitchcockian mystery, as the film progresses, we learn more information about each character which gives us clues to their involvement final scene.

The short fragments of the film highlight the seeming emotional distance and alienation in contemporary Austrian society. The often mundane and trivial scenes of these characters are a comment on the seeming insignificance and banality of human life. Haneke sees us all as merely drops in an ever-expanding ocean.

7. Der siebente Kontinent [The Seventh Continent] (1989)

This film is the first in Haneke’s Glaciation trilogy focusing on the banality and alienation of everyday life. The film follows three years in the lives of the well-to-do Schober family Georg (Dieter Berner), Anna (Birgit Doll) and their young daughter Eva as they live their mundane existence.

The family is seen living their ordinary lives – going to work/school, cooking meals, doing the grocery shopping etc. But a sense of deep malaise and disconnection slowly creeps over Georg and Anna and after much deliberation they decide the only way to free themselves and their daughter from their mundane existence is through self-annihilation, methodically destroying all their worldly possessions in the process.

.

This slow-burn drama from Haneke utilizes many visual distancing techniques such as the use of extreme close ups so we cannot see the character’s faces and a distinct lack of dialogue to make the film hit emotionally hard.

The final scene in which the family violently and coldly destroys their belongings is a wonderful comment on the un-importance of materialism and the futility of existence. Like his other films, Haneke does not provide any motivations or explanations on why such an extreme and violent act occurs, which disturbingly makes us question our satisfaction with our own lives.

6. La Pianiste [The Piano Teacher] (2001)

In Haneke’s provocative and erotic thriller, middle aged piano teacher Erika Kohut (Isabelle Huppert) lives at home with her overbearing and controlling mother, while her father resides in a mental asylum.

Despite her successful job, Erika is weak and struggles for autonomy and fears the loss of respect from her students, even getting jealous of their talents. In spite of her austere and professional demeanor, Erika lives a very lurid existence behind closed doors; a secret life of voyeurism, sexual repressions, sadomasochistic fetishes, self-mutilation and inner turmoil.

When handsome, young and talented piano player Walter Klemmer (Benoît Magimel) manipulates Erika into giving him private music lessons, the two of them begin a dangerous and unsettling sexual relationship based on control, humiliation and fantasy-fulfillment.

.

Adapted from the novel of the same name by Austrian Nobel Prize winner Elfriede Jelinek, La Pianiste is a complex and challenging film which explores the dynamics of power and submission within relationships – sexual and otherwise, using a frame of Freudian psychosexual analysis.

Huppert is brilliant as the severe and deeply disturbed Erika, who is a prisoner of her own desires. Erika cannot live without brutality – towards others, but most of all towards herself – she is a master of self-discipline and self-destruction.