Filmmakers love to take inspiration from the Spaghetti Western. The genre, popular mainly from the late 1960s and the early 1970s, represented a decade’s worth of the most exuberant and stylized cinema. To this day, many filmmakers take stylistic cues from the genre’s many legendary moments. It was anchored in the idea of using the audiovisual experience unique to film to make the most out of every moment, no matter how small. The slightest move of a hand hovering over a gun, the slightest adversarial look from one gunslinger to another, became the stuff of breathtaking suspense in the final edit.

Composers like Ennio Morricone and Riz Ortolani composed themes that are to this day instantly associated with the genre and the period it represents. For the directors such as Sergio Leone and Sergio Corbucci, moments that linger in the consciousness were forever made. Unlike many movements, there were actors like Lee Van Cleef and Woody Strode who, at one time or another, seemingly worked almost solely within the genre.

This, as fans will note, makes the genre both distinct and self-contained. Indeed, with its grizzled actors, soaring themes, deadly adventures, and shameless excitement, we have rarely seen such a distinct visual movement since and may not see the like again for some time to come.

15. Day of Anger (1967)

With one of the most famously scintillating opening credit montages of the Spaghetti Western genres history, so too does it open this list. In fact, the rambunctious tone of the opening moments of this film are, in fact, an apt indicator of what has continued to lure devotees to the genre through the eras. The almost Warhol-esque animation of Lee Van Cleef and Guiliano Gemma’s faces, punctuated by a feisty score and brightly coloured gunfight montage what many may see as a borderline absurdism. What follows is our introduction to the town of Clifton- complete with chamber pots and blind misfits. It is pure opera, pure Spaghetti Western.

For his part, Lee Van Cleef (the genre’s most ubiquitous star) plays the senile gunslinger Frank Talby, who is plagued by a literal madness. When he commits a murder, the heat is on for both himself and his long suffering, but skilled young protegee Scott “Mary”. Scott’s innocence endears us to him, this is a man who learned to draw without owning a gun. But when a journey to collect 50,000 dollars turns sour, it becomes an every man for himself affair.

As is often the case with the genre, the story is a mere Hitchcockian “McGuffin”, aimed at setting up the ecstatic showdowns that the film canon prides. Riz Orlani provides fans with a still cherished score, and the direction from lesser-known Tonino Valerii is lively. In this case, any character lucky enough to ride off into the sunset does so more or less unchanged rogue.

14. A Bullet for the General (1966)

Any Spaghetti Western scholar will tell you that the Zapata Western is an idea that is crucial to understanding the genre. A Zapata Western involves the use of the western format out of the context of the West, specifically in the context of revolution. A Bullet for the General, Damiano Damiani’s influential 1966 opus is perhaps the finest example of the Zapata convention.

It opens on a plagued Mexico in which bandits are routinely executing civilians. “Il Gringo”, however, is not altogether bothered by this. As the aloof American watches on, the bandit Chucho, aided by a military leader tied to a crucifix, pulls off a siege on a train full of armed soldiers. The stakes are high from the beginning in this tale of serendipitous meeting and reluctant partnership between different men.

Family ties and loyalty are key to this film. Klaus Kinski’s Santo believes much more idealistically in the revolution than his more simple-minded bandit brother. Furthermore, the nihilistic Bill “Gringo” Tate is caught capriciously in between, keeping us guessing. There is much compound storming, and many ambiguous characters; particularly hypocritical authority figures. Martine Belswick is gorgeous and luminous as Adelita, one of the genres best female figures. In the end, the audience is left to decide for themselves as to whether or not the character’s revolutionary allegiance was at all warranted in this most mature of westerns.

13. The Grand Duel (1972)

Even in a genre that prides itself in making the biggest possible event from every fleeting moment, The Grand Duel is seen by fans as a true grand opera. The generation gap looms ever present as a world weathered former Sheriff helps a man framed for murder to confront the three brothers who want him dead. As always, a small town becomes an arena of battle in which both heroes and villains are made.

The score is as essential as it has ever been in the genre, but with a harmonica meandering at a suprisingly gentle pace and a slow tempo guitar track, the score present here is more pensive than most. As such, the film itself has its own rhythm.

As a villain in bright white suit murders a defenseless old man, one is aware of the flamboyant iconography of the genre; not to mention the presence of machine guns and bold set pieces. But each moment is so intensely composed with what seems to be a palpable passion that the films oft trodden narrative ground may be forgiven by fans. A slow-building confrontation on an old ranch is particularly vivid. Furthermore, with Lee Van Cleef in a sympathetic role, one of the great thespians of the genre can be rooted for to the bitter end.

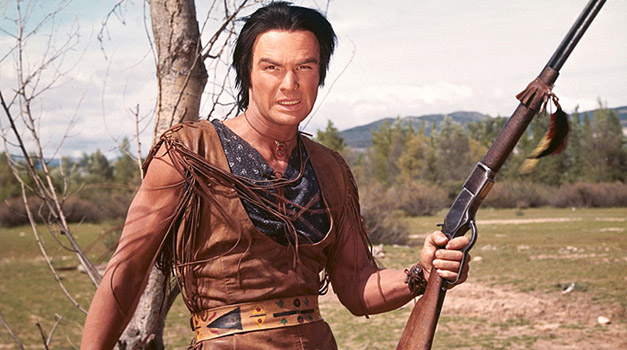

12. Navajo Joe (1966)

Once described by Burt Reynolds as the worst film he has ever done, this vigilante flick has nevertheless endured and found increased appreciation from fans of the genre over the years. Certainly, the film is disturbingly comfortable with murder, even by the standards of the western. The film’s brutality is certainly cause for classifying it as genre revision. As such, it’s place on this list has been earned.

There are many elements present here that are staples of the genre. The railroad has long been a muse for films in the western canon. Here the simple setting of a train’s carriage is the scene of both innocence and depravity. However, the main revision here is that of cowboys and indians. Often played too simply, the old cliche is turned on its head by torture, rape scenes, and murders in cemeteries. Bloody revenge is the ideal from the beginning. Reynolds may not have realised it, but his revenge film is, in fact, one of the starkest tales of the Native American plight on film.

11. For a Few Dollars More (1965)

Sworn enemies join forces in Sergio Leone’s cynical first sequel to A Fistful of Dollars. Eastwood’s Man with No Name decides to form a tentative union with the brutal Col. Douglas Mortimer (Van Cleef) to track down bandit Indio and his crew. It is noted to be one of the darker films in Leone’s canon, murderous from the very first shot, which is oddly static by comparison to the montage openings of other Spaghetti Western films.

Marked by a distinctly strong cast that includes appearances from Klaus Kinski and Mario Brega, the films is nonetheless dominate by the charisma of Eastwood, Van Cleef, and a chilling turn from Gian Maria Volonte as Indio. It is a film that plays deep into the minds of brutal men as Indio and Mortimer are particularly frank about that which they have done to others. Eastwood and Van Cleef’s play the tension between their characters with expected applomb. The films ending, anchored in a recurring motif of a pocket watch, is known for it’s haunting beauty. This is seen by many as an almost uncomfortably human film.

10. The Mercenary (1968)

In one of Corbucci’s most widely appreciated films by fans of the genre, western favourite hero Franco Nero is pitted against oft villain of choice Jack Palance in a confrontation stemming from the domination of an entire people. When a simple man named Paco rebels against his despotic boss, it is an act of proletariat revolution. Polish mercenary Kowalski (Nero) agrees to defend him and his newfound silver at a price. at a price. The complication arises when Curly (a brutal Palance) becomes a thorn in their collective side.

There is both an absurd comedy and a viciousness to this film. Paco is a simple man, almost a sentimental dreamer. Tony Musante plays him as out of his death following the murder of his cohorts the Garcia brothers at the hands of Curly, and continues in the this vein for the remainder of the film. He is, however, a hopeful influence on the film. Fighting for Mexico as a whole, the audience is inclined towards empathy with him, even when this is not the case for Kowalski. An execution themed finale is particularly lively and, in it’s conclusion, we note that this film has become something of a bizarre buddy movie.

9. The Big Gundown (1966)

Boasting one of the most likeable roles ever assigned to Lee Van Cleef, this film sets out to be a romp from the start. Another quintessential hired gun yarn, Van Cleef’s Johnathan Corbett is hired by the cride politician Brokstan to pursue the supposedly ruthless man known only as “The Mexican” for the murder of a young girl.

Corbett’s myth is thoroughly built by way of a dramatic opening scene and a typical boisterous scene in which he plays off of an unimpressed town sheriff. For it’s pat the trademark scenarios of the genre come aplenty, a sequence set to Beethoven (which heavily inspired a similar sequence in Django Unchained) establishes the characters thoroughly through an extended set piece.

The stand offs between the Mexican and Corbett are intense, in particular their first encounter in a shanty town as Corbett interrupts Mexican as he is getting shaved. Intense too is a passionate affair between the Mexican and a rancher woman which introduces the femme fetale element present and luminous in so many films of the genre. There is, too, a political conspiracy element that may come as a surprise, as all is not as it seems with the initial murder charge made against The Mexican. However, this merely adds to what is perhaps a shamelessly exuberant adventure film, all be it an occasionally brutal one.