Horror as a genre has remained to this day primarily trapped in the shadow of the Western world, at least in the public consciousness. The fact is, however, an appreciation and thrill for the sensation of a chill down the spine is a universal desire, almost a drive, and areas all over the world have produced their own corpus of horror masterworks waiting to be discovered.

One of the more famous crazes was the modern J-horror renaissance that began in the late 90s and petered out in the mid-2000s, but Japan has been producing horror films for decades. Horror, as a manifestation of a society’s inner-most fears, not only transforms over time but melds to the consciousness of the nation that produces it, and as such Japanese horror sees a number of particular through-lines as fascinating to dissect thematically as to confront with a primeval chill.

To this extent, here are 15 of the best Japanese horror films stretching from the modern era all the way back to silent classics from an alien world.

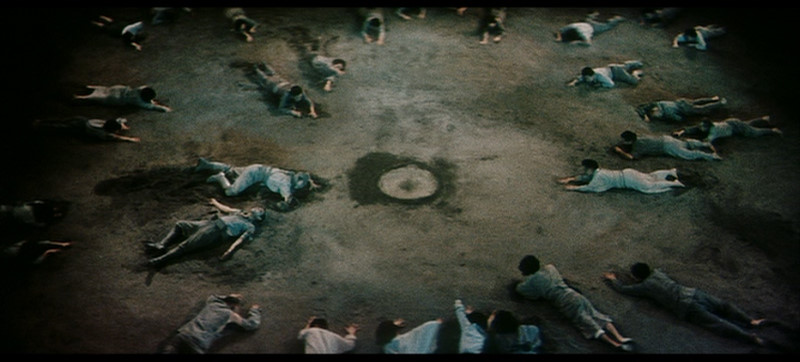

15. Suicide Club (Sion Sono, 2001)

It’s almost a statement of fact that the narrative is a mess in Sion Sono’s droll dark comedy horror, but the sloppiness only adds to the film’s alien artifact curiosity. The story about a mass suicide craze sweeping Japan’s teenage youth plays out more like a rough idea that a fully formed concept, but the odd cinema verite style gives it an uncommonly creepy earthiness that contrasts smartly with the freak-out quality of its bloodletting and hyperbolic storytelling.

The dry comedy is a nice touch, the quintessentially East Asian rejection of individual leads in favor of process-oriented storytelling is a fascinating kick in the pants to narrative storytelling, and Sono proves a visual journeyman to boot; an early moment where a almost-black blood surrounds a pristine white bag and Sono holds on the shot is inspired.

14. Jigoku (Nobuo Nakagawa, 1960)

Replete with hellish imagery that depicts with an astounding bluntness the moralism of Japanese horror cinema, Jigoku is at once one of the more palatable mid-60’s J-horror films for today’s ever-violent audiences and one of the most esoteric. Its story, set in the modern day, naturally has a more modernist twang with a small dash of mod flair that gives the opening moments a sleek cool that director Nobuo Nakagawa then devotes the film to subverting.

Once his main character Shiro (Shigeru Amachi) descends into the depths of hell (after wracking himself with guilt for his involvement in a hit-and-run), everything sleekly artificial about the product festers and implodes on itself in a firestorm of color-coded, sickly hued hellacious imagery that attains a fever pitch even by the standards of 60’s Japanese horror.

Nakagawa’s film provides one of the most lurid, lustful versions of hypnotic cinematic hell ever captured on celluloid, going straight for the gut with an almost pop-art attack and losing its mind in the process.

13. Ju-On: The Grudge (Takashi Shimizu, 2002)

A film with virtually no narrative coherence and a complete lack of psychological tension or steadily mounting dread over the course of its already slim 90 minutes is not necessarily most people’s cup of tea, nor are jump scare parades necessarily critical darlings for discerning horror viewers. But Takashi Shimuza’s J-horror film (released in 2002, right at the peak of the J-horror explosion) holds together for one, and only one functional reason: very sharp jump scares, some of them masterful, and all of which meld together to compose a solid majority of the finished product.

It is not artistically sound on paper, and the linking narrative for the sequences is fairly poor, but the pure craftsmanship of the sequences f horror themselves win over in the end (and this resolutely episodic narrative, about the ghost of a boy who preys on all who take up residence in a specific house, is clearly aware that it is functionally an excuse for exquisitely crafted jump scare sequences). Particular note should go to the sound design, which mimics a jagged croaking noise over and over and curdles the blood every time.

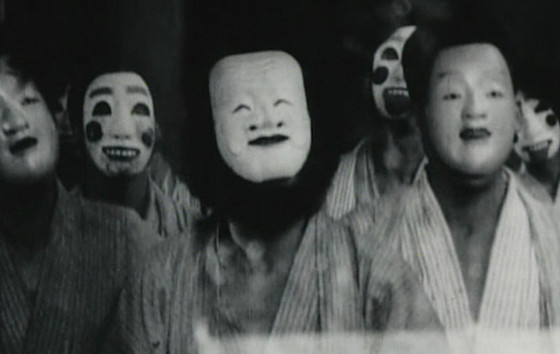

12. A Page of Madness (Teinosuke Kinugasa, 1926)

Teinosuke Kinugasa’s surrealist horror is a grand paradox of a film, a work that approaches us like a time capsule from an alien past and a bullet into the future, earning its cheekily subversive title by openly flouting any sense of realism in favor of its School of New Perceptions-dusted carnivalesque sideshow of wonders and amusements.

A Page of Madness is a calling card for the defining early silents in the avant garde strain of non-classifiable cinema that is only meaningfully “horror” in the sense that its parade of images and sounds can’t but frighten and vex due to their dissonant non-narrative obstructiveness.

Kinugasa’s film plays like a greatest hits collection of its time period, dancing with German Expressionism shot through with Soviet Montage and some of the naughtier, more sexually charged MittelEuropean works to come out of various orifices of the world around this time.

But its intermixing of ghostly wonders and feudalistic fable stylization, its disharmonious synthesis of archly-composed image and ear-scratching warbles that impersonate sound, concoct a uniquely Japanese potion that would form the ground level of all that would be so wonderfully arcane and oracular in J-horror’s future.

11. Dark Water (Hideo Nakata, 2002)

Hideo Nakata’s follow-up to his monstrously successful Ringu series showcases why he kick-started the genre, and how his films alone (along with Takashi Miike, who was never only interested in horror) managed to transcend a ubiquitous craze that was more notable for box office success than critical acumen.

What always separated Nakata’s work from his fellow filmmakers, beyond his impeccable craftsmanship, was his undercurrent of melancholy that favored mounting tension and saw horror as a cousin of pure overpowering sadness. He looked into the human mental state and saw it for the frail, brittle construction it was, and his films play out with a critical mass of dread lacking in so many other modern J-horrors.

Dark Water is not his scariest film, nor is it his best, but it is his most fully felt tragedy, and when real world tragedies breed horror, a worthy and satisfying horror film you have indeed.

10. Kuroneko (Kaneto Shindo, 1968)

Kaneto Shindo’s Kuroneko attains the rough-hewn texture of a forbidden creature long locked away in the inner chambers of the human mind, only now unleashed with bestial might on unsuspecting viewers. It’s a sensuous pleasure that finds the cryptic clashing to a fever pitch with the tactile and immediate, a work of beauty that rejects safety and modernity at every turn for something lost in the shadows.

Shinda’s crisp chiaroscuro cinematography complements his lurching camera that starts and stops arrhythmically, both of which emphasize the film’s jagged emotions and high-contrast storytelling. The music, by longtime Shindo collaborator Hikaru Hiyashi, is a high point for all of cinema, combining the bestial with the symphonic into a mix as much animalistic as man-made, confrontation-ally emphasizing Japan’s past at a time when the nation was often eager to move forward with Western world desires.

It’s a feral growth of a film that refuses to be burned off, a slinky, punishing cat o’ nine tails that hurts the mind as much as the body.

9. Ringu (Hideo Nakata, 1998)

The beckoning light of modern Japanese horror and a beacon for future things to come, Hideo Nakata’s Ringu takes a simple story of a video that kills those who watch it and elevates it to brutally elegant high art. Like most Japanese horror, it deals forthrightly with temptation, but it takes a classical theme and throttles it into the modern age.

Giving us a videotape that we “must not watch for it will kill us” and then teasing us with the specifics of the tape sees Nakata implicate his audience in our own modern voyeuristic quest to thrill and chill with increasingly gross video watching (and cinema watching, for that matter).

He cryptically and methodically lures us into his sinuous web with a quiet chill and low-key, classical suspense, titillating us with the audience-baiting idea of the script before unleashing our inner desire – to always watch for something “dangerous” on video – back onto us.